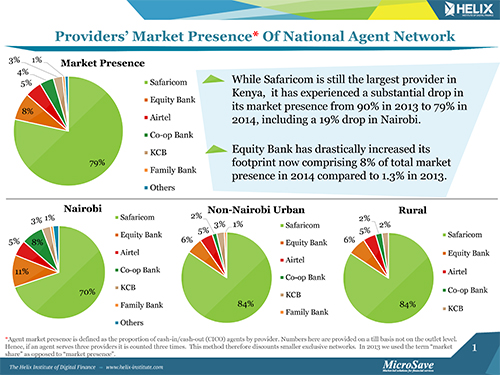

Since the launch of M-PESA in 2007 the story of digital finance in Kenya has been synonymous with that of the story of M-PESA. However, data just released from The Helix Institute of Digital Financeshows that this now seems to be changing, which is exciting to watch, and also important understand. In 2013, The Helix Institute survey of over 2,000 agents in Kenya showed that 90% of the agents in Kenya were providing services for Safaricom‘s M-PESA. However, as shown in the below chart, that percentage has declined to 79% in 2014, a drop of 11%. This means other providers in the market have been growing their agent networks at faster rates than that of M-PESA. Who has been doing this and how, help us understand what this might mean for the future of digital finance in Kenya.

Phenomenal Transmutation

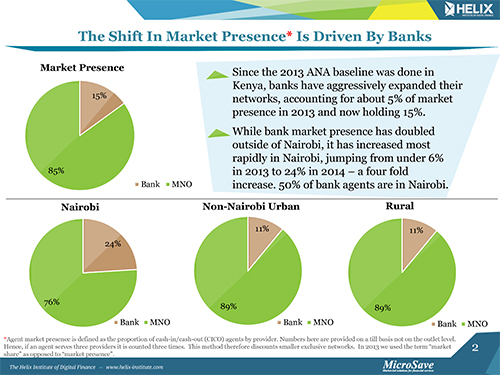

The first interesting insight is that the shift is not from one mobile network operator (MNO) to the other, which is most common in other markets given MNOs’ ability to scale quickly. Airtel Money in Kenya only increased market presence by one percentage point between 2013 and 2014, and the rest of the top six providers are banks. The shift is a transmutation of the network itself, from a network of almost purely mobile money agents, to one where bank agents also have a significant market presence. The below chart shows banks’ market presence grew threefold from 5% to 15% during the period. This aggressive expansion has been led by Equity bank, which single handily improved its market presence from 1.3% in 2013 to 8% in 2014 as well as Co-operative bank and KCB.

Where and how the banks are expanding is also informative. There has been an accentuated transmutation in Nairobi, where banks have increased market presence four-fold, jumping from just under 6% in 2013 to 24% in 2014. Currently 50% of bank agents are located in Nairobi. Further, while 73% of bank agents were exclusive in 2013, only 26% percent were in 2014, likely showing a new strategy to recruit existing M-PESA agents, as opposed to new retailors, which may have been a major catalyst for growth during that year. However, banks usually manage agents from their bank branches and therefore recruit in areas surrounding them, and it is unclear now how much longer a strategy like this will be sustainable, as suitable agents near bank branches become harder to find.

What’s on the Horizon?

While some may think that Kenya is headed in the same direction as Tanzania, with multiple providers holding significant market presence, we think the story is more complicated than that, as eluded to above. It does seem that banks will continue to grow larger agent networks in Kenya, and there was a similar trend in Tanzania of shared networks emerging first in the capital city and then expandingoutwards. However, the big differences between what has happened in Tanzania, and what is happening in Kenya, is that the subsequent movers in Kenya are banks, while in Tanzania they are telecoms. This is important because banks in Kenya have very different abilities for continued growth, and also a great potential to create a more sophisticated ecosystem of service offerings.

Are Past Gains Indicative of Future Growth?

Banks usually have different business objectives for building networks, are subject to more restrictive regulation, and tend to design their networks differently in Kenya, commonly using a hub-and-spoke model based on their branches. In terms of business objectives, some banks just want to decongest their branches, and do not have the ambition for big scale that telecoms do. Further, regulation often makes it harder for banks to register new customers, which is the fuel they need to sustainably grow large numbers of agents quickly. Lastly, the hub-and-spoke methodology might work fine for a first tier of expansion around branches, however, expanding to the rest of the country becomes an issue at some point and requires a shift in strategy to scale further. Therefore, while there was an impressive growth of bank agents relative to mobile money agents between 2013 and 2014, it is unclear if this trend can or will continue moving forward.

The Potential for Real Evolution

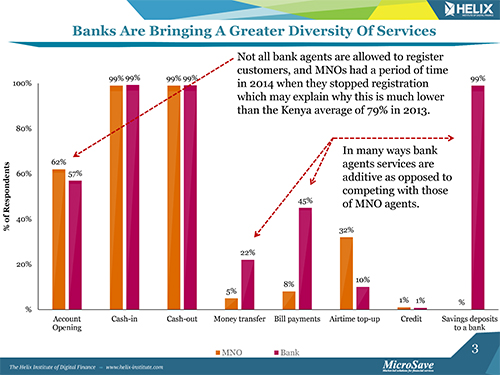

The other real difference with what is currently happening in Kenya, is that this market shift has the potential to be an actual evolution in the utility of the system as opposed to just having more players competing to offer the same services, to the same people, over the same channels. The new bank players in Kenya seem to be expanding the transactional pie, as opposed to just further fracturing the existing one. Kenyan bank agents offer a different array of services to customers through the agent channel, as shown in the chart below, and transactional data shows that bank agents conduct significantly higher transaction values than mobile money agents, which means customers are using them differently. Hence, bank and mobile money agents do not necessarily compete. Therefore, banks and MNOs might be able to find ways in which they actually prefer to complement each other to further increase available services in the ecosystem and reduce the costs of offering them.

Conclusion

The shift in market dynamics in Kenya is exciting given how long it has been the story of a single player. However, it is still unclear if it will continue, but if it does, it seems that it will likely lead Kenya down a different more dynamic path than other countries which have multiple players competing. Hopefully the new services banks are offering to customers will be seen as beneficial to a more digital ecosystem and partnerships as opposed to price wars will emerge. There is hope for this given the recent partnerships between Safaricom and CBA to offer M-Shwari, Safaricom and KCB to offer KCB M-PESA Account, and Airtel and Equity on the MVNO. Given the difficult strategic operations and expenses associated with managing an agent network, areas like liquidity management, agent training, and monitoring might be good places to extend partnerships, effectively spreading the spirit of co-opetition between banks and MNOs offering mass market finance in Kenya.

It is easy to conclude that as dependence on PDS goes down, inclination towards receiving the DBT rises. However, in order to make sure that all the categories of beneficiaries are ready to shift, it is imperative to move their reference points with regards to PDS. In case of AAY beneficiaries, the new reference point will be “choice” and “assurance”. It will be choice of shop from which to buy, and the assurance of being able to buy an equivalent quantity (unaffected by “leakage” or price fluctuations) and better quality of commodities. For BPL beneficiaries, the new reference point will be the ability to choose to buy the equivalent quantity/quality of commodities at a convenient time – without the fear of forfeiting rations because they are unable to visit the FPS in the brief window it is open. APL beneficiaries will be focused on the convenience of choosing the time and place to buy their kerosene without the hassle of standing in queues.

It is easy to conclude that as dependence on PDS goes down, inclination towards receiving the DBT rises. However, in order to make sure that all the categories of beneficiaries are ready to shift, it is imperative to move their reference points with regards to PDS. In case of AAY beneficiaries, the new reference point will be “choice” and “assurance”. It will be choice of shop from which to buy, and the assurance of being able to buy an equivalent quantity (unaffected by “leakage” or price fluctuations) and better quality of commodities. For BPL beneficiaries, the new reference point will be the ability to choose to buy the equivalent quantity/quality of commodities at a convenient time – without the fear of forfeiting rations because they are unable to visit the FPS in the brief window it is open. APL beneficiaries will be focused on the convenience of choosing the time and place to buy their kerosene without the hassle of standing in queues.

First, the new Kenya Commerical Bank (KCB) M-PESA account, offered through a partnership with Safaricom, seems to be taking off rapidly. Chief Executive Officer Joshua Oigara said that over 50,000 people are now registering for the account every day, and that

First, the new Kenya Commerical Bank (KCB) M-PESA account, offered through a partnership with Safaricom, seems to be taking off rapidly. Chief Executive Officer Joshua Oigara said that over 50,000 people are now registering for the account every day, and that