Mobile money providers in Uganda are well aware of the Over The Counter (OTC) trap and its implications, but their response to it will be the subject of another, later blog. This blog examines why OTC matters – enormously – to all stakeholders in digital financial services (DFS).

As highlighted by Pawan Bakshi, in “Beware the OTC Trap”, OTC can be used by providers to achieve scale at the beginning of the life cycle of their DFS agency roll-outs. However, the effects can be severely debilitating if the provider hits scale relying on a high proportion of OTC transactions.

In response to this discussion, I conducted a small survey in Wandegeya, a suburban market in Kampala, located within 5 km from the city center with nearly 120 mobile money agents. I asked 23 agents drawn across all the mobile network operators (MNOs) on their thoughts about OTC and found out some interesting results:

- 50-55% of cash-in transactions effected by agents are OTC – the amount is directly debited from the agent’s till and credited to the receiver’s wallet.

- The agents charge customers an extra, unofficial amount for OTC despite receiving a commission from the providers. This means that the agent is earning twice (from the customer and the MNO).

- The agents prefer OTC because of its added revenue to their business.

- The agents are aware that they are cheating the customer; I would also imagine most customers are also aware of the extra, unofficial fee, but still go ahead with the transaction.

- The agents admit that the practice of OTC is common across all of Uganda’s agent networks.

The Uganda agent network accelerator (ANA) survey, conducted in mid-2013, highlighted that on average an agent in Uganda makes 30 transactions daily (this could now have increased with the passage of time and further maturation of the market). Today Uganda has an approximate total of 45,000 active (on a 30-day basis) agents. This means that we have approximately 1.35 million transactions each day at mobile money agents, using the findings from the national survey.

From the 23 agents transaction records (gathered from agent transaction books), they register close to 52% as cash in a transaction (so approximately 700,000 transactions daily countrywide) and 50% of these cash in transactions are OTC (350,000 transactions daily countrywide).

The median cash in the transaction in Uganda lies between UgSh60,000 – 125,000 (US$23-49), for which the provider pays the agent UgSh440 ($0.17). Providers pay these commissions even though, of course, they derive no revenue from most of the transactions, in the hope that the cash in will generate revenue from person to person (P2P) transactions made by the customer. However, OTC allows a customer to make a direct deposit to another (who in most cases immediately withdraws it) and thus the provider only makes income on the cash withdrawal and foregoes the P2P. Yet it is the P2P where the providers make most of their profit since the costs of effecting the P2P are negligible, whereas much of the commission charged for withdrawals are paid to the agents providing the service. See Ignacio Mas’ outstanding Pricing of Mobile Money for a discussion on this.

The charge for P2P transfers for these median transfers of UgSh60,000 – 125,000 (US$23-49)is UgSh4,400 (US$1.72), and with the direct debit nature of OTC into the receiver’s account, this is not realized by the provider. This forms a very significant opportunity cost for the provider.

To assess approximately how big a loss the providers are incurring by permitting OTC, I looked at the 100 transactions from the 23 agents I interviewed and found the mean direct cost to the provider from payment of commission for cash-in to the agent of US$0.16; and the mean opportunity cost of loss revenue from P2P transfer of US$1.57. Multiplying this by the 350,000 OTC transactions each day gives a daily loss (direct and opportunity cost) of US$605,500; which converts to over US$221 million per annum.

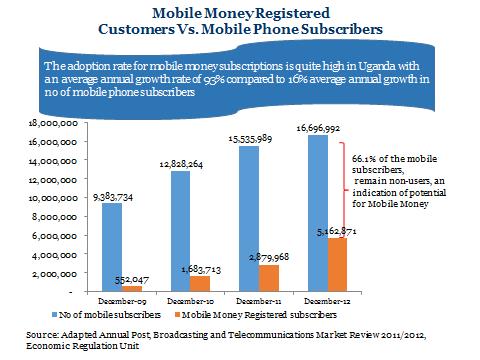

So what is the impact of OTC on the growth rate of mobile money in Uganda? According to the 2013 Uganda communications commission (UCC) report, the use of mobile money is doubling each year but is this the true potential growth rate? Uganda is estimated to have 17 million mobile phone subscribers, yet there are only 5.2 million active (on a 30-day basis) mobile money users. This is despite the fact that over 9 million users are already registered with at least one provider for mobile money.

So how is OTC stifling active subscriber growth in Uganda’s DFS space?

1. Customers do not need to register for DFS: The customer enters into a comfort zone where he can send money without necessarily registering or activating his SIM card with any MNO for mobile money. Incidentally, OTC is also prevalent for cash outs too, as long as the customer has the withdrawal codes from the wallet from which the money is to be taken, as in the case of one of the leading providers. Many such customers will not be easily convinced to subscribe their mobile numbers to mobile money – particularly with the growing levels of fraud in Uganda.

2. Agents have limited motivation to register customers and earn more from unregistered customers: Through OTC, agents are earning double revenue: from the provider (in cash-in transaction commissions) and from the customer (in unofficial fees). They prefer to have more customers conducting OTC transactions. Registering and converting customers into active mobile money users also takes time, and therefore less interesting for agents.

So what next for DFS providers in Uganda?

In Beware The OTC Trap: Is There A Way Out? Pawan argued that addressing the OTC trap requires a mindset paradigm shift. Providers need to conduct a deep dive analysis into and to develop an understanding of, the implications of OTC transactions especially for scaling both volume and value of transactions. This paradigm shift must start with the providers accepting that OTC can be greatly minimized (indeed, in Kenya, M-PESA has almost eliminated it as the ANA survey for Kenya shows). But the journey towards zero OTC environment starts with providers and requires collective action and effort. In Uganda, my discussions indicate that some MNOs some believe OTC transactions are impossible to eliminate, while others believe the elimination of OTC is possible.

Marketing and communication will be key to these efforts and must address all levels – the providers, agents, master agents and, above all, customers who need to know their rights and understand the benefits of carrying out their own transactions … as well as the fact that agents’ supplementary charges for OTC transactions are not sanctioned by the providers.

In Beware OTC Trap: Are Stakeholders Satisfied? we highlight that OTC is a double-edged sword that rarely, if ever, really meets the ultimate needs of any of the stakeholders involved.

Customers are paying additional fees and losing the opportunities and flexibility that self-initiated transactions offer them. Needless to say, agents have also burnt their fingers offering OTC transactions. It is considerably less risky for them to transact directly with a customer’s phone right in front of them.

For providers looking to limit the churn in their voice and data customers, need to enroll and activate these customers into mobile money irrespective of what stage of business life cycle mobile money is in.

Ultimately, the provider needs to ask if encouraging OTC is worth the inherent risks for short-term expediency. What is the revenue loss involved, especially if they reach scale? And how many subscribers do you forego by allowing agents to offer OTC services? And what is the reputation risk of agents charging at will for OTC transactions?