Youth is a potential segment to provide financial services as they constitute a huge proportion of the world population. Beyond the sheer numbers of youth, there are several other reasons why this segment has to be considered as having great potential to provide these services. Despite youth being an important segment for providing financial services there are many challenges around it. MSC has worked with several financial institutions and other stakeholders in making this financial services provision a little easier. In this video, the speaker, Veena Yamini Annadanam describes the challenges in product development for youth and outlines MSC’sapproach to addresss these challenges. In addition to market research, systematic product development, MSC focuses on building financial capability of the youth and working with parents, communities as support groups and policy makers to create an enabling environment for financial institutions to offer these products.

Blog

Government subsidy in microinsurance: A necessary trend?

For quite some time, the world of microinsurance has been debating the role of government (more specifically government subsidy) in the growth of microinsurance. While commercial microinsurance – where the client pays a premium for their policies underwritten by an insurer – paved the way for innovative and efficient ways of delivering insurance services to the low-income people, these programmes have rarely achieved impressive outreach.

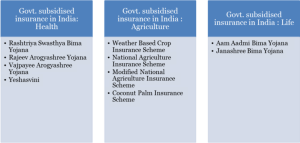

Meanwhile, governments have entered the sector with subsidized insurance programmes of various kinds, targeted at the lower income people. Though these government-subsidized insurance schemes often look similar to social security schemes, they are different fundamentally. While in traditional social security schemes, the government underwrites the risks and pays for the services, in this new generation of programmes the government pays the full (or a part of) premium, while the risk is underwritten by insurance companies.

Many argue that these schemes are not “microinsurance” in true spirit since often either client voluntarily subscribe to them, or do they pay the premium (or full premium) … and in some cases both! However, these schemes occupy a significant position in any discourse about the sector, since both of them are similar in function – they cover insurable risks of low-income people. Interestingly, these schemes do not fall under the purview of ILO’s definition but qualify as microinsurance in the definition coined by IAIS.

ILO Definition of Microinsurance:

Microinsurance is the protection of low-income people against specific perils in exchange for regular premium payments proportionate to the likelihood and cost of risk involved.

IAIS (International Association of Insurance Supervisors) Definition of Microinsurance:

Microinsurance is insurance that is accessed by low-income populations, provided by a variety of different entities but run in accordance with generally accepted insurance practices.

During the “Landscape of Microinsurance in Asia and Oceania” study, MicroSave came across many such schemes and were challenged to distinguish them from commercial microinsurance. We realized they are fast closing the gap with commercial microinsurance and hence it was unwise to let them fall outside the purview of the study. We landscaped these government subsidized microinsurance schemes as “social microinsurance” in the study, an idea we found limited buyers that time.

We are pleased to see that this idea has recently been endorsed by Michael McCord, a global veteran and leader in the field of microinsurance . While he argued in favor of government support in health insurance, we believe the logic can be extended in case of agricultural insurance, too. This learning is based on our recent project on weather index insurance in five Asian countries.

In the traditional agriculture insurance programme, viz. National Agriculture Insurance Scheme (NAIS) of India, the Government supported insurance companies in both ways: a) claims subsidy and b) premium subsidy. This resulted in a startlingly poor financial performance with a 640% claims ratio (for every INR100 of premium collected, NAIS paid INR640 as claims!!). The reasons for such high claims ratios might be poor design and/or non-actuarial pricing. However, without the government support, the insurance companies would never have come forward to offer this product (except maybe the public insurer AIC).

Based on the recommendations of a study by the World Bank and GFDRR in April 2011, the Indian Government modified the NAIS and called it mNAIS (modified NAIS). Under the mNAIS programme, the government provides an only premium subsidy, and the insurer has to bear the responsibility for claims. Since the underwriting risk is now carried by the insurer, they take extra care in the pricing and management of the scheme. The government’s role also helps the scheme non-financially, as it has now mandated all recipients of subsidized crop loan to avail the mNAIS facility, which has, in turn, helped the scheme achieve impressive outreach. The percentage of loanee to non-loanee farmers in India is 98%, which shows the role the government mandate played in creating the outreach.

Government subsidy is also extended to index-based agricultural insurance programmes of India (in addition to the traditional insurance schemes). Index insurance settles claims on the basis of measuring some proxy indicator (such as temperature, rainfall, wind speed, humidity etc.) in contrast to measuring the actual yield itself. India is the global leader in weather index insurance running the largest weather-based crop insurance scheme (WBCIS). Again, one of the main factors for success has been government support. Under this scheme, the farmer pays just one third the premium, and the remaining two-thirds are shared by the state and central governments. This way the premium ‘burden’ on the farmer is less, making them more willing to purchase the insurance product. There is an abundance of such full or part subsidized schemes in India. China, Georgia, Indonesia, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Nepal, Pakistan, Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam are some other Asian countries with strong government subsidized microinsurance (or “social microinsurance programmes”).

In Asia, social microinsurance has an outreach of nearly 1.7 billion as compared to a little over 170 million insured through commercial microinsurance. This differential in outreach is a clear indication that government subsidy is instrumental and, quite probably, necessary in the growth of microinsurance, at least until the programme stabilizes (becomes sustainable and arrives at claim ratios of less than 100%). The government essentially plays the role of a market maker until the social microinsurance products are perfected, their delivery innovated and the outreach scaled up. However, the important question here would be when should the Government stop subsidizing these programmes … and, indeed, will it ever be able to do this considering the political compulsions! Perhaps part of the answer lies in a gradual phasing out of the subsidies as poorer populations experience benefits accruing to them and insurers make their products and delivery channels more robust.

Expanding access to finance for small businesses in India: A critique of the Mor Committee’s approach part 3. Assessing access to finance for small businesses?

The first blog in this series highlighted the context of the Mor Committee’s recommendations and the significant gap between the supply of and demand for credit for small businesses. The second blog in the series examined the role of the banks, development finance institutions and non-bank financial institutions (NBFCs) to examine why they have been so backward in coming forward to meet this gap. This concluding blog looks at the ways of measuring access to finance for small businesses.

Credit to GDP Ratio – Is it a good measure to assess access to finance for small businesses?

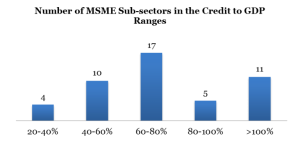

The Mor Committee report recommends that by January 2016 every significant (more than 1 percent contribution to GDP) sector and sub-sector of the economy should have a credit to GDP ratio of at least 10 percent. The Committee recommends the use of credit to GDP ratio to assess the extent of credit reach to various sectors in the economy. The report highlights that India at its abysmal 70 percent credit to GDP ratio is way below the averages of high-income countries (200 percent) and the middle-income countries (100 percent). The Committee argues that targeting 10 percent credit to GDP ratio for all significant sectors by 2016 would catalyze inclusive growth and subsequently reduce poverty.

At the small businesses level, the report presents the finding that the credit to GDP is 35 percent at an aggregate level. Similarly, at industry and services level, the ratio stands at 56 percent and 25 percent respectively.

In our analysis of subsectors within the MSME segment at the two-digit level of NIC-2004 classification, MicroSave found that of 47 sub-sectors only five, namely Food Products and Beverages; Textiles; Chemicals and Chemical Products; Basic Metals; and Fabricated Metal Products contribute greater than 1 percent to the GDP. In terms of access to finance, these five subsectors had comfortable access ranging from 49 to 101 percent. Thus, we observe that while credit to GDP may be a good ratio to determine access to credit at the aggregate and sectoral level, at the sub-sector level it does not hold relevance.

Also, the targets assigned for January 2016, at 10 percent credit to GDP is not relevant for the MSME sector per se as all the sub-sectors within MSME segment have greater than 10 percent credit to GDP ratio. The credit flow is skewed in favor of medium enterprises with micro enterprises languishing for want to institutional credit.

A World Bank study highlights that access to credit is inversely related to firm size. Size is a significant predictor of the probability of being credit constrained and hence micro and small enterprises are highly credit constrained. In such as scenario, credit to GDP ratio would not sufficiently reflect the access to credit to small businesses. Lack of a clearly articulated and representative ratio may mean that the banks and financial institutions would expand access to credit to the MSME sector as a whole by focusing largely on medium-sized enterprises.

Thus, it would be worthwhile to use the formal credit to capital ratio to measure the access to credit by small enterprises. The underlying assumption upon which this indicator is suggested is the fact that it clearly defines the leverage of the enterprises. Also, in our opinion, instead of looking at MSME sector as a whole, it is important, for the purposes of measurement of access to credit to look at the micro, small and medium enterprises individually.

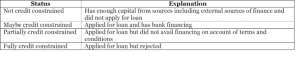

Another measure in line with the suggestions of World Bank’s report on the assessment of credit constraints for enterprises is the credit-constrained status of the micro, small and medium enterprises. World Bank suggest that the enterprises can be classified as below:

The status of all enterprises across the size ranges can be assessed periodically to estimate the access to finance. This will provide a better understanding of the access to credit amongst micro and small enterprises, and thus focus policymakers’ attention on these key drivers of Indian economic growth.

Who is the user in “user-centred design”?

In 2000, we had completed two years of what we thought was outstanding work to understand the needs, perspectives, and aspirations of the end customers for banks and microfinance institutions. It was time for MicroSave–Africa’s first mid-term review, led by industry gurus Beth Rhyne and Marguerite Robinson … and they gave us a wake-up call.

They noted, “The mid-term review of MicroSave-Africa found the project to be outstanding in articulating client perspectives …. MicroSave-Africa‘s … excellent market research training course has already given 16 MFIs a new perspective on clients and tools (focus group discussion and participatory rapid appraisal techniques) to learn about client needs more effectively. MicroSave-Africa has not done as well on the supply side, in part because it has underestimated the complexity and scope of the work needed to introduce new products successfully inside MFIs.”

We had developed a series of qualitative research tools and techniques that helped (and continue to help) hundreds of financial institutions develop new and refined products that are used by millions of people in Africa, Asia, and Latin America.

But this success could not have been achieved without clearly understanding exactly who uses these products.

The obvious “users” are the end customers of the financial institution or mobile network operator. But as our mid-term review highlighted, there is another very important “user”: the organization that will deliver the product. MicroSave has been running training and technical assistance on product development and innovation for 15 years now, and we have repeatedly seen two challenges:

- When an external agency conducts market research and hands a beautifully constructed product prototype to a financial institution, it has a high chance of becoming a “product orphan” – unloved and rejected by its prospective parents. External agencies can rarely adequately understand the institutional needs, culture and operational realities of the financial institution. So, more often than not, the product prototype is not adequately profitable, or conflicts with other operational realities, or presents insurmountable challenges for the IT systems and so on. External agencies from different countries also often fail to understand the regulatory environment or cultural nuances of the target market – particularly if they insist on arriving with “optimal ignorance”.

- Even when the market research is conducted by staff of the financial institution in collaboration with MicroSave (our preferred model) we sometimes see their perspectives shift from being to an institution focused to the other end of the spectrum and being to customer focused. In between these two extremes lies the “sweet spot” for products that are market-led but meet the institution’s needs and realities. Institution-focused financial services ignore the market and end customers’ needs, perspectives and experiences; but over customer-focused products can be too complex, or simply not adequately profitable to deliver.

The solution lies in building qualitative market research capacity within institutions so that the tools and techniques can be used not just for product innovation but also for a myriad of other drivers of customer-centric or market-led financial services: customer service, marketing & communications, corporate brand & identity and so on. And so that the products developed are based on the needs of both the customers and the institution that serves them, as well as an adequate understanding of the regulatory environment.

Indeed, we at MicroSave would argue that the most successful financial institutions (and indeed other corporations) have in-house market research capability. Equity Bank is a very good example of this – we trained six of Equity’s staff on qualitative market research in 2001-02, and this team helped guide the bank from 75,000 customers in 2000 to over 1 million by end 2006. Equity then underwent a massive expansion, and in 2010 came back to MicroSave asking us to train a new cadre for its “Research and Product Development” cell because the original staff that we had trained had either moved up within the organization or had moved on. This new cadre is now working with us to develop the products for rollout across the bank’s digital finance channels and for its operations in Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, and South Sudan. Equity Bank now has 8.7 million customers in Kenya alone. They are perfectly positioned to balance the needs and perspectives of the customers and the bank.

The users in “user-centered design” are necessarily both the customers and institution that serves them … and not as one fresh-faced consultant announced to colleagues of mine, “the donor who pays my bills”!

Expanding access to finance for small businesses in India: A critique of the Mor Committee’s approach part 1. Background and the supply gap

In 1966, the Hazari Committee on industrial licensing recommended nationalization of banks, which changed the Indian banking industry fundamentally. After a gap of nearly forty-five years, a similar path-breaking effort has been initiated by the Reserve Bank of India, in the form of the Committee on Comprehensive Financial Services for Small Businesses and Low-Income Households. The Committee and its report are part of an explicit and dedicated effort to expand the ambit of financial services from partial to full inclusion of small businesses and low-income households in India. The Committee’s terms of reference included the formulation of design principles to develop institutional frameworks and regulation and development of new strategies to achieve full inclusion and deeper financial support. Chaired by Nachiket Mor, the Committee tabled its report in a record time of four months. The report, with its visionary and reformative recommendations, aims at significantly and fundamentally overhauling the entire banking industry in India. The report’s bold and ambitious recommendations have so far received a range of responses from critics, ranging from wholehearted support to skepticism, from wonder to bewilderment. While the report has its fair share of ambition and optimism, in our view there are parts that are aptly conceived and its recommendations in the light of best practices and global learning make sense. In this blog, we critique the Committee’s approach with respect to enhancing access to financial services for small businesses in India.

Considering that small businesses were an integral part of the target segment, the report’s following observations and recommendations have the potential to impact the delivery of financial services to small businesses fundamentally:

- “Close to 90 percent of small businesses have no links with formal financial institutions. There exists robust and visible demand by small businesses for a wide range of financial services. Currently, this demand is being serviced by informal sources.”

- “The current approach of full-service, national level, scheduled commercial banks using their own branches and a network of mostly informal agents is a case of “too much for too little” as access is low compared to risks and costs.”

Apart from these observations, the Committee also recommends that by January 1, 2016, there should be:

“High-quality, affordable and suitable credit for all small businesses from conveniently accessible formally regulated lenders. It further establishes the need for full inclusion of small businesses with regard to basic payments and savings, and risk and investment products.”

For market making impact, the Committee suggests the following:

“DFIIs such as NABARD, CGTMSE, and SIDBI should re-orient their focus to be market makers and providers of risk-based credit enhancements rather than providers of direct finance, automatic refinance, or automatic credit guarantees for banks.”

In addition, the Committee recommends that by 2016, every sector and sub-sector of the economy with more than 1 percent contribution to GDP would have a credit to GDP ratio of at least 10 percent.

In three parts of this blog, we dissect each of these observations to assess why and how it can impact enhancing access to financial services by small businesses in India. We also showcase examples of similar initiatives that have yielded far-reaching impact in terms of bridging the demand-supply gap for financial services.

- Demand and Supply Gap for Small Businesses Financing in India

One of the key observations of the Committee is that 90 percent of the small businesses are self-financed. Regulators, donors and financial institutions have constantly raised this issue on several platforms and flagged it as a challenge that needs to be addressed on a priority if India is to attain its dream of full financial inclusion. The reason is obvious, as, in a developing nation like India where the country’s growth is being fuelled by vibrant small businesses, the lack of adequate finance mars the growth of the small business sector and in turn impacts on the growth of the nation.

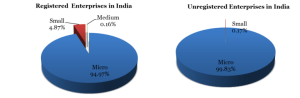

An analysis of financing to enterprises reveals that small businesses face a major gap in financial services. India has 1.8 million registered and 29 million unregistered enterprises. 95 percent of registered enterprises and 99 percent of unregistered enterprises are micro-enterprises.

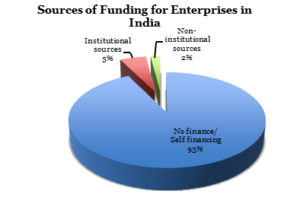

As per the annual report 2012 from the Ministry of MSME, Government of India, only about 7 percent of enterprises have access to finance from institutional and non-institutional sources.

As per the annual report 2012 from the Ministry of MSME, Government of India, only about 7 percent of enterprises have access to finance from institutional and non-institutional sources.

93 percent of such enterprises rely upon self-finance, which includes the entrepreneur’s savings and short-term loans from friends, family, and relatives.

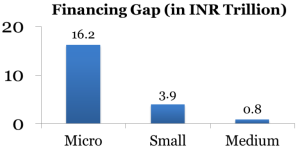

The International Finance Corporation, in its 2012 Research Report estimates that the finance gap for small businesses is a whopping 96 percent. The report estimates that of the INR 20.9 trillion MSME finance gap, INR 19 trillion is the debt gap and INR 1.9 trillion, is the gap in equity.

In the next blog in this series, we examine why financial institutions are unwilling or unable to sieze the market opportunity to fill this gap.

Whose cash is it anyway? Several agent solutions to cash security

Agents everywhere have trouble breaking even. Reasons are numerous (click here for the easy blog overview and here for MicroSave‘s comprehensive Policy Brief on Indian Business Correspondents), but first and worst among their complaints is how to manage all that tempting, eminently stealable money—both in their shops or kiosks and en route to and from designated bank deposit/withdrawal locations.

Bank branches are too far, and often too unwelcoming, for poor, rural and urban clients expecting government disbursements and/or with their own earnings to remit or deposit. This is particularly true in India where close to 70 percent still live in villages, internal migration to industrial cities continues apace (two out of every ten or ~240 million Indians are migrant workers), and many of them have too little income to ever really interest retail banks anyway. Agents, or business correspondents (BCs) as they are known here, manage cash-in and cash-out transactions for these individuals near their home and work with easier hours and surroundings.

For the past five years, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been well aware of the daunting—and expensive–security risks these BCs experience daily in their role as local bank representatives. One RBI solution has been specified “cash routes” with transit insurance paid for by the sponsoring banks, but these secured routes are not available to all agents in all areas. Unreliable technology and lack of bank interoperability also complicate agents’ liquidity management and liability. The result is high BC turnover and dissatisfaction—plus too many robberies and very few bank reimbursements to date for these losses.

But wait…

This is not just another hand-wringing dirge about the Plight of the Poor Agent and the failure overall of the BC model. In fact, a MicroSave field research team recently came across BCs in Bihar, a state in Eastern India, who are competing successfully with, and even occasionally attracting more customers than, regional rural banks in the area with lower commissions and more flexible hours, most notably during peak-volume holidays and festivals.

Nevertheless, theft is an ever-present problem for them as well. Many of these agents in different districts of Bihar are handling INR.500,000 -1,000,000 /USD 8,333- 16,666 and 100+ customers a day. This can mean at least two visits to the link bank to replenish cash or deposit one morning’s intake. These frequent trips are not along the secure “cash routes” mentioned above, and most agents have no formal insurance, nor do their customers. The BC network managers and the link banks are theoretically responsible, but most apparently do nothing to reimburse the loss. So agents and customers must somehow cope.

Agent ‘Arrangements’

And cope they do. Surprisingly well in many cases. Here are several strategies we observed in our fieldwork:

- Arrangement 1: Amarendra Prasad Singh, age 38 years, has had all the usual problems most agents do: a large personal investment (INR100,000 /USD 1666) up front to establish his bona fides with his corresponding bank and to start the business; power shortages and weak internet connectivity which he must supplement with auxiliary electricity, data cards, and multiple SIM to create backups for system failures; and, of course, robbery which could easily erase his daily profits and INR 30,000/USD 500 monthly commissions.

Initially, Amarendra had high hopes RBI or his link bank would come up with a remuneration scheme in the event of theft, but he has since taken it upon himself to manipulate public perception regarding his cash flow. He opens his shop next to his house (where he has ample cash reserves) at 10 am sharp, but he allows no withdrawals until 10:45 because, as he tells his customers (and anyone else who might be listening), his associates are at the bank collecting cash and won’t be back before then.

He also lets it be known that he does his own bank business early when the branch opens. In fact, when he has to withdraw or deposit large sums, he goes at noon as inconspicuously as possible. And though he has business hours on Sunday, he only offers account opening and balance enquiries, again to deflect the notion that he keeps any cash at home.

- Arrangement 2: Shailesh Kumar’s profile is similar to Amarendra’s, but his strategy differs. He makes at least two trips a day to his link branch located 5kms away. Each visit he withdraws INR 200,000 – 300,000/USD 3,333- 5,000 and carries it back to the shop. But he never goes at the same time or takes the same route. And he tells no one his schedule except the person accompanying him. He varies his withdrawal routines as well, using ATMs instead of his link branch and multiple debit cards for smaller denomination withdrawals. Shailesh also uses only four-wheel vehicles instead of two-wheel bikes or motorcycles to conduct bank business as he believes cars are safer and the money is easier to hide.

- Arrangement 3: Ajay Kumar, an agent operating in one of the more remote villages in the area, has already been robbed once. He claims he never even realized that his activities were being tracked on his regular visits to his link branch. He lost INR 80,000/USD 1,333 and even after six months of repeated requests to the bank and his network manager, he has received no reimbursement. Ajay now rents a shop much closer to the branch and has moved most of his business there. He well understands that this is very inconvenient for his village customers, but by substantially reducing his former operations, he also reduces his chances of losing large amounts of their money and his profits.

- Arrangement 4: In a few cases, link branch managers actually seem to understand agents’ security concerns and try to co-operate to the extent they can. One manager granted agents in his operating area a “green channel” which meant the bank cashier allowed BCs to withdraw cash privately from a special chamber in back of the bank. (This practice ended when a new branch manager arrived and now all agents for that link bank wait in long queues along with everyone else, with minimal safety measures, often for hours at a time.)

- Arrangement 5: Several BC network managers are also making an effort to improve security for their agents and have created insurance pools whereby every agent contributes Rs.500 each month. These sums are then used to help cover losses. A four-member committee which includes the BCNM head decides which claims are valid and how much to award. At present, BCNMs are not in a sufficiently strong position to offer better money insurance and their agents do not earn enough to pay the premiums for real cash-in-transit insurance.

Arrangements 4 and 5 only serve to underscore what agents know already: they take the hit for cash that is never actually theirs. The money belongs to the customer while the bank, the institution with the full deposit-guarantee insurance, holds the funds until the customer withdraws them. Agents are only the luckless, uninsured intermediaries.

No one thinks this is fair (except possibly the banks) and RBI has finally, in a recent notification, acknowledged that the responsibility of cash insurance should indeed rest with banks. BCNMs now have huge expectations. We would like to believe they are justified, and in the meantime, we look forward to more and ever-better coping strategies from enterprising agents.