UNHCR Cash-Based Intervention in Meheba refugee settlement in Zambia: The Journey to Digitization.

Blog

Water Supply & Sanitation Finance and Lending

The transition from concessional to commercial financing has stimulated the private sector to crowd in and invest more in the sector over the last two decades.

Is Blending Finance The Answer?

Despite increased global efforts towards ensuring the world achieves universal access to safely managed water supply and sanitation services, sector financing needs continue to lag demand.

Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana: A demand-side diagnostic

The Indian government launched the Pradhan Mantri Ujjwala Yojana (PMUY or Ujjwala Scheme) in May 2016. This initiative aims to provide clean cooking fuel to households that have traditionally relied on either firewood, coal, or dung cakes or a combination of the three as a primary source of cooking. Since its inception, the Ujjwala scheme has already provided low-cost LPG connections to more than 50 million beneficiaries.

However, a little over a year after the scheme’s launch, media reports highlighted the challenge of low refill rates by PMUY beneficiaries. MicroSave conducted an independent assessment of PMUY beneficiaries in M.P., Chhattisgarh, and U.P. from November 2017 to January 2018, to understand the reasons behind the low uptake of PMUY refills. The objective of the study was to examine the efficiency, efficacy, and operational aspects of the scheme and understand the triggers and barriers that drive the behaviour around usage and refills of LPG by the PMUY beneficiaries. The study tries to answer the following key research questions:

How effective has the PMUY scheme been in reaching the intended target segment?

How different is the profile (demographic or usage) of PMUY beneficiaries from “typical”

LPG users?

Have PMUY beneficiaries who use LPG stoves stopped using traditional fuels such as

Firewood or biomass completely?

What are the triggers and barriers that impede the high uptake of PMUY refills?

What are the ways to improve the uptake of PMUY refills?

Fintechs for LMI segments – Tapping the untapped

In our first blog in this series, we highlighted how the low- and middle-income (LMI) segments in India present immense opportunities for ecosystem players.

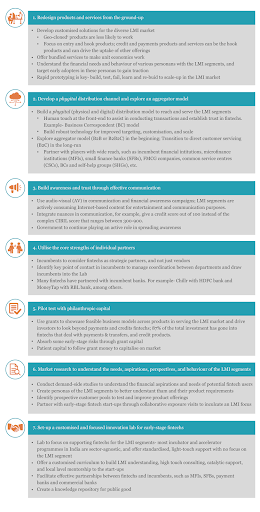

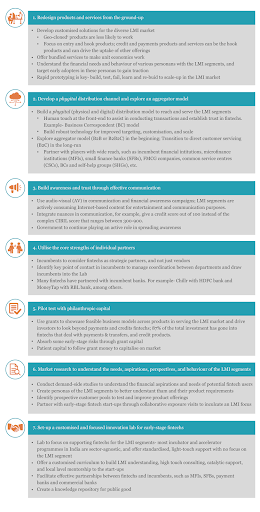

Concisely, the processes through which the ecosystem players can engage with the LMI market effectively requires rethinking from the ground-up. This rethinking would include a redesign of products and services, explorations around combination of digital and physical outreach efforts, and effective, pro-poor communication from the supplier-side. Incumbents need to collaborate with fintechs and build on their respective strengths. Moreover, considering the economics of the supply-side, certain experiments would require philanthropic capital to create viable business models.These players may include fintechs, incumbents, investors, and donors, among others. In the earlier blog, we also deliberated on how the ecosystem has been moving towards an inflexion point, and why the time is right for stakeholders to venture into this space. This blog is the concluding part in this series. It highlights how ecosystem players can serve the LMI market and tap its potential.

|

The exhibit below presents seven possible ways in which ecosystem players can tap the opportunities in the LMI market. These ways require innovation and re-engineering that focuses on client-centricity and spans channels, communication, products, and partnerships.

The need for a dedicated innovation lab

To boost the LMI space, an innovation lab dedicated to early-stage fintechs is a potential solution. MicroSave and CIIE, with support and guidance from J P Morgan, have used the research findings, their experience and expertise to conceptualise, set up, and manage a ‘Financial Inclusion Lab’.

The Fintech Inclusion Lab would aim to achieve the following:

- Be dedicated to provide customised support to the fintechs that focus on LMIs;

- Become a platform that brings together fintech start-ups that show an intent and willingness to serve the LMI segments;

- Support early-stage fintechs to innovate and provide digital financial solutions to the LMI market;

- Offer differentiated support, high-touch consulting, and local-level mentorship to the start-ups;

- Facilitate effective partnerships between fintech start-ups and incumbents that operate in the LMI space;

- Provide opportunities to fintechs to connect with investors which might be interested in follow-up funding for their business venture.

To support the larger innovation space, we will create and share learning and knowledge products in the public domain. Watch this space for more updates on the Lab.

Geo-cloning is the term given to the act of replicating successful business models from other geographies in a new geography.

Fintechs for LMI segments – Tapping the untapped

In our first blog in this series, we highlighted how the low- and middle-income (LMI) segments in India present immense opportunities for ecosystem players.

Concisely, the processes through which the ecosystem players can engage with the LMI market effectively requires rethinking from the ground-up. This rethinking would include a redesign of products and services, explorations around combination of digital and physical outreach efforts, and effective, pro-poor communication from the supplier-side. Incumbents need to collaborate with fintechs and build on their respective strengths. Moreover, considering the economics of the supply-side, certain experiments would require philanthropic capital to create viable business models.These players may include fintechs, incumbents, investors, and donors, among others. In the earlier blog, we also deliberated on how the ecosystem has been moving towards an inflexion point, and why the time is right for stakeholders to venture into this space. This blog is the concluding part in this series. It highlights how ecosystem players can serve the LMI market and tap its potential.

|

The exhibit below presents seven possible ways in which ecosystem players can tap the opportunities in the LMI market. These ways require innovation and re-engineering that focuses on client-centricity and spans channels, communication, products, and partnerships.

The need for a dedicated innovation lab

To boost the LMI space, an innovation lab dedicated to early-stage fintechs is a potential solution. MicroSave and CIIE, with support and guidance from J P Morgan, have used the research findings, their experience and expertise to conceptualise, set up, and manage a ‘Financial Inclusion Lab’.

The Fintech Inclusion Lab would aim to achieve the following:

- Be dedicated to provide customised support to the fintechs that focus on LMIs;

- Become a platform that brings together fintech start-ups that show an intent and willingness to serve the LMI segments;

- Support early-stage fintechs to innovate and provide digital financial solutions to the LMI market;

- Offer differentiated support, high-touch consulting, and local-level mentorship to the start-ups;

- Facilitate effective partnerships between fintech start-ups and incumbents that operate in the LMI space;

- Provide opportunities to fintechs to connect with investors which might be interested in follow-up funding for their business venture.

To support the larger innovation space, we will create and share learning and knowledge products in the public domain. Watch this space for more updates on the Lab.

Geo-cloning is the term given to the act of replicating successful business models from other geographies in a new geography.