MFIs transforming into Small Finance Banks will face capital restructuring challenges. SFBs will have to depend on their customers’ deposits, shareholders’ equity along with ‘refinance’ facilities from bulk lenders. In this Note we discuss how SFBs can build a first class retail institution, focussed on low-income clients. It is safe to conclude that transformation of MFIs to SFBs is challenging – particularly since MFIs have only extended credit to date. In order to transform from “credit only” to “deposit mobilising” institutions, they will have to work on many areas. Some of these areas are 1. Brand repositioning 2. Investment in human capital, and 3. Complimenting savings with payments.

Blog

Transformation of Microfinance Institutions into Small Finance Banks: Will it be a Roller Coaster?

“In 2013, Dr. Nachiket Mor committee recommended differential licensing in the form of two categories: i) Payments Bank, and ii) Small Finance Bank (SFB) to further financial inclusion in India. There are various perceived challenges when MFI have to transform from their existing credit led structure to full service small finance bank. Challenges are largely perceived in capital restructuring following RBI guideline to reduce the bank loan exposure to three – four times of their net owned fund and replace it with deposits mobilised from the customer. Challenges become momentous considering arrival of payment bank tapping the same market segment.

In this Note, we discuss various challenges that MFIs may face while transforming to small finance bank and plausible solution in the subsequent note.”

Designing an Effective User Interface for USSD: Part2

In the first part of this blog series “Designing an effective user interface for USSD”, we presented a comparative analysis of various access channels used for accessing mobile money services. This blog presents the behavioural insights from the user perspective based on the recent research conducted by MicroSave with a leading MNO in five geographies. The research aimed to gauge the experience of semi-literate mobile money users who access their mobile wallets using USSD channel. These insights will hopefully help providers simplify and re-design user interfaces, especially for users like Suraj.

WHERE ARE WE

The insights detailed below emerged from MicroSave’s field research specifically focussed on USSD based user interfaces.

a. Users are “number literate”

a. Users are “number literate”

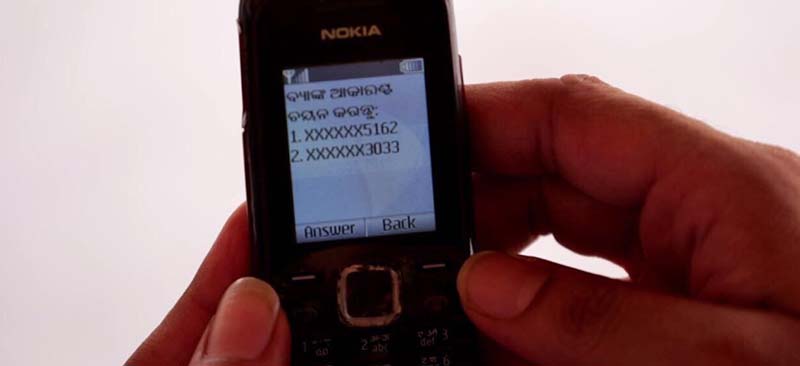

Numeracy is prevalent even among less/un-educated respondents. Most users often learnt the navigation flow by using only “numbers”. For instance, users quite comfortably used the short code *400*2*1* for self-prepaid recharge. Even new users, after a guided session, were able to memorise short codes/ numeric strings (like *100*1*1*2#) for completing their transactions. The preference for memorisation avoids the need to navigate multiple screens, thereby helping the users to locate the required option instantaneously and reducing transaction time.

b. Users suffer from a “tyranny of choice”

Like most of us, the respondents also face the paradox of choice. The user group often got confused while locating required service from various options on the main menu. This means that the “long list” type of menu is not suited for these users. In the USSD menu of one of the MNOs, instead of one option like Send Money, there are multiple options such as “Send Money to bank” and “Send Money to Money Wallet” which often confused users.

c. Users are “text averse”

Most users are not comfortable reading wordy options such as “Send to other mobile”, “Send money to any bank account” and “प्रीपेड रिचार्ज दूसरों के लिए” (Hindi for prepaid recharge for others). In the absence of additional help or detailed explanations (lack of which is a major limitation of USSD), these phrases look ambiguous to the respondents. Such phrases and sentences fail to solicit the required input from users.

d. Users do not prefer “unrelated” clubbing

d. Users do not prefer “unrelated” clubbing

The respondents often do not understand the sub-menu options displayed under a main menu option. This confusion is often due to presence of sub-menu options, which instead of being clubbed with “similar/complementary” main menu option, are present under “different/unrelated option”. For instance, on USSD main menu of an MNO “Agent locator” (a sub-menu option) is clubbed with “My account” (a main menu option). The users, however, perceived that “My account” option would display their profile details, mini statement, change/forgot password options etc.

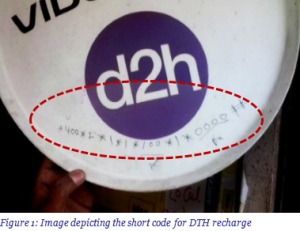

Such unrelated clubbing of options also obstructs the discoverability of required mobile money services while navigating the mobile money menu. For instance, in the utility bill payments option, clubbing two different types of payments such as one-time payments (for example, charity) and recurring payments (such as DTH recharge) often leads to confusion.

e. Users often get confused with some “terms”

The present USSD menu is laden with complex terms and banking jargon such as merchant, beneficiary etc., which are not well understood by the users. This hampers navigation, since users are less likely to discover services buried among a bunch of unfamiliar terms. Interpretation of certain banking terms in Hindi (which are quite complex as well) such as आदाता (Receiver), लाभार्थी (Beneficiary) etc. is often more difficult.

WHERE WE’VE TO GO

a. “Geography” specific main menu

While a broad range of mobile money services are offered, the services which see aggressive adoption by users varies from location to location. The use-case differs substantially among users in rural and urban areas. In rural areas, for instance, users prefer mobile wallets for DTH recharge; whereas in urban areas, bill payments have seen widespread uptake. Send Money, similarly is preferred in urban areas and Withdraw Money is more common in rural areas.

USSD menus should be redesigned by considering geography specific needs. Subsequently, various main menu options should be prioritised. Users will not only find the USSD menus more appealing, relevant and tailor-made, but will also avoid navigating less/un-important options.

b. “Limited” unbundled main menu

Mostusers prefer an explicit ‘unbundled menu’ with limited number of options. Needless to say, “re-designed menu” must consider the small screen size limitation of widely used basic and feature phones; as these users otherwise may not prefer scrolling multiple (vertical) options. Such a menu should host geography specific, “basic” and “frequently used” services. Overall, an unbundled menu must be designed to simplify the “discoverability” of useful mobile money services.

c. Nesting only “complementary” options

The sub-menu options should be aligned and clubbed under “relevant” and “complementary” main menu options. Related service features/options should be housed under one “umbrella” term; which is easy to understand. Such bundling will significantly improve the interpretation, awareness and usability of sub-options. For example, an option such as “Agent Locator” can be clubbed with a main menu option such as ‘Send Money’, as the location of the outlet (for P2P transfer) at cash-out geography is of prime importance to the sender.

d. “Customised” menu based on usage history

Usage behaviour of the mobile money users can be leveraged to explore the possibility of a “dynamic” main menu. This feature presents an option to derive a “new” USSD menu depending on users’ transactions behaviour. The main menu options, can get automaticallyprioritised and present a “re-designed” and “customised” menu to its users. Providers, of course, will find it technologically challenging to design such a dynamic menu as the follow-up sub-menu options are dependent on user’s inputs.

e. Using “familiar” terms

Most of the respondents, both illiterate and semi-literate using mobile phones and money transfer services, were familiar with certain English terms used commonly in banking and telecom industry. Words such as sender, receiver, recharge, balance, cash-in etc. are self-explanatory and easily understood. These terms can be used to “simplify” the interpretation of mobile money services, thereby limiting the degree of mediation required.

In addition to the suggested changes, the providers may further “create” and “promote” simple and easy to use numeric strings for some of the frequently used mobile money services such as prepaid recharge, DTH recharge, send money etc.

Navigation in itself, of course, does not necessarily offer a standalone solution for simplifying user’s experience. However, the design of USSD menu certainly influences adoption and degree of usage of mobile money. The need to design an easy and intuitive USSD menu, hence cannot be undermined.

Designing an Effective User Interface for USSD: Part 1

Suraj is an illiterate migrant from Muzzafarpur (Bihar) who works at a construction site in Delhi. He has recently opened a mobile wallet with a leading mobile network operator (MNO) in India. When we met him, his primary concern was – “How would I use my (mobile money) account, when I don’t even know where to find the required service?”

Users like Suraj represent the target customer group for mobile wallet service providers. One of the common attributes of this user group is the inability to use mobile money services on their own. This necessitates mediation from a family member or an agent to conduct a transaction. The most quoted reason for facilitation is the difficulty faced in “locating” various service offerings.

The user interface (UI) plays a vital role in facilitating usability and enhancing user experience. Globally, mobile money service providers offer different access channels such as mobile application, internet, unstructured supplementary service data (USSD), interactive voice response (IVR) and SIM toolkit (STK). MicroSave came up with a comparative analysis of some of the commonly used access channels, please see the image below for details.

The choice of a particular access channel is dependent on various factors such as technology requirements, handset capabilities, cost of use, security concerns, ease of use etc.

In a developing country like India, most mobile phone users still own basic and feature phones. USSD, which is cost effective for the MNOs and is accessible from all types of phones, is, at present the best available option to reach the mass market. This view is also supported by the fact that USSD is used by most large scale deployments across the world.

COMMON TYPES OF USSD MENU

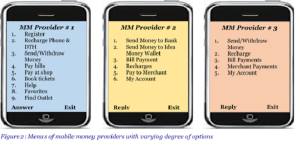

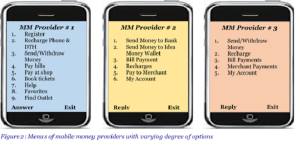

USSD menus can be broadly categorised as bundled and unbundled. Generally, a bundled menu, with limited options in main menu,  requires more navigation for exploring sub-menu options (see figure 2).

requires more navigation for exploring sub-menu options (see figure 2).

An unbundled menu, on the other hand, has a detailed/long list of options in the main menu itself. Here, the extent of navigation is reduced as there are limited sub-menu options. While navigating through the USSD user interface of various mobile money providers, it can be seen that both the types of menus (with varying degree) are prevalent in India.

In the second part of this blog series “Designing an effective user interface for USSD”, we highlight insights into the behavioural aspects of users when using mobile money services via USSD.

Business Correspondent Channel Cost Assessment

MicroSave conducted the costing study with 4 BCNMs in India. This report discusses key findings related to the costs incurred per transaction by different stakeholders (including banks, BCNMs and BCAs) in facilitating branchless banking transactions. Findings from this study will help policy developers and other stakeholders devise a sustainable delivery model to offer financial services to the financially underserved population in India.

Cooperation or Competition

In our last blog we presented an analysis of the 11 players that have received the “in principle” approval from Reserve Bank of India to operate the payments banks. None of the Over the Counter (OTC) remittance players got the license which surprised many in the payments and financial inclusion arena. This blog talks about a major upheaval in the OTC market post the announcement of the payments bank licenses.

While conducting OTC transactions the sender does not need to have a wallet or a bank account as these transactions are agent initiated. The sender hands over the cash to the agent, the agent debits his account/wallet and credits the receiver’s bank account. MicroSave has debated about OTC being a trap here, here and here. But, the fact is that the remittance business in India is huge and largely dominated by OTC service providers who either have a Pre-paid Instrument (PPI) license or are a business correspondent (BC) of a bank.

In the OTC business the end customer is normally oblivious (unless the agent is exclusive) to the service provider used to remit his/her money and the actual transaction fee. It is the agent who gets to choose the service provider to remit customer’s money. This autonomy of the agent stems from the fact that the service providers always find it difficult to own the customers hence they focus on agents to service the customers. In the current state of remittance business where exclusivity of the agent is becoming extinct and one agent is being acquired by 5-6 service providers, it is not an exaggeration to say that, “The Agent is the King”.

So what factors trigger the agents’ decision to choose a particular provider? The recent field studies conducted by MicroSave in the immensely competitive remittance market of Indian metro cities suggest that agent commission is the main trigger. The agents have access to multiple service providers and for obvious reasons, prefer the highest paying service providers. There are a few exceptions wherein service and operational support are placed ahead of pricing as triggers. But, all this has changed with the midnight stroke of clock on August 31st 2015. We can now see a new paradigm of strategic co-opetition (co-operation with competition) in which all the major PPI players, that collectively control a majority market share of remittance business, have joined hands and reached to an agreement to extend universal pricing for OTC transactions.

This agreement essentially means that all the service providers charge the agent with a standard rate as agreed. So agent commission is not a decision trigger anymore.

With this change in place few areas that the service providers will have to delve deeper and with more seriousness than ever before are:

- Technology: The service providers will have to rework their front end and back end technologies to make it flawless. Service uptime needs to come at an acceptable level, applications need to scale up to avoid any time out, the user interface of the portals will have to be simplified, and the processes for mandatory fields need to be more intuitive with minimum information for faster and effortless flow. As agents say, ROTI (Return on Time Invested) must go up.

- Operational support: Agents would gravitate towards service providers that provide excellent operational support by proactive communication. Reactive approach towards grievance handling will fall way behind the proactive approach in the race of winning agent’s trust. Service providers will have to define aggressive TAT (turn-around-time) for grievance redressal and will have to ensure that the timelines are strictly adhered too. Similarly, marketing and promotional support will be of more importance than ever.

All these factors were equally important for building a sustainable business but the market perhaps favoured better pricing. Now with universal pricing, these factors will drive the business and differentiate one service from another.

The revised universal pricing, as it stands today, would translate into increased margin for most of the service providers. The service providers may also like to invest this surplus to create better experience for their partners and achieve competitive edge. The service providers will need to continuously innovate to sustain the edge.

Some of the players who are party to the mutual agreement of having universal pricing will surely have business implications in the shorter run. This is because, with a uniform pricing structure in place, their agents will now earn substantially less (20-50%) per transaction. It will be interesting to see how these service providers handle the uproar from the agents.

The feelers from the market tell us that the agents are already anticipating other incentive schemes to keep them motivated despite the universal pricing. The other implication could be higher prices for the customers till competition comes in.

Two facts force us to think that this agreement is a ripple effect of the payments bank licenses. First- almost all of the service providers who have agreed to have a universal pricing structure, failed to get payments bank license. Second is the timing of this agreement which comes in only days after the payments bank licences were announced. Only time will tell whether is it really the effect of payments bank licences or not, but for sure the way of working of service providers is up for an overhaul.

The other open question is whether it is a step in price discovery for remittance business in India? Or it is beyond this wherein we can see co-opetition from various players in payment industry.

Keep reading, we will bring more insights into the rapidly changing payment market in India with a variety of players.