India’s Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) is the largest food security distribution network in the world. The National Food Security Act (NFSA) 2013, aims to cover 75% of the rural and 50% of the urban population through this network. The network also provides employment for 478,000 Fair Price Shop (FPS) owners, their employees, and hired labour, who work across the supply chain in corporations and godowns. In order to curb diversions, FPS automation was proposed. In this Note, we specifically talk about the revised commissions proposed by the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs (CCEA) of Rs.70 (US$1) per quintal of ration and an additional Rs.17 (US$0.25) per quintal for FPS owners making sales through Point of Sale (POS) devices are not proving enough for FPS onwers. With these levels of commissions, many FPS owners are likely to close their shops. In the end we recommend developing an economic model to optimise the business case for FPS owners.

Blog

Low Cost Housing Markets

Access to housing is a basic right and is important in improving livelihoods of poor people. There have been various efforts to support the poor to access low cost housing. MSC recently with support from Habitat for Humanity International and some microfinance institutions in Kenya, supported the development of housing microfinance to improve housing situations among low income people. In this video, George Muruka, Senior Specialist, Private Sector Development, at MicroSave speaks on the key concerns affecting low cost housing market in Kenya.

Savings Achieved through FPS Automation: Step for Greater Efficiencies

Under the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) system, state governments give licenses to Fair Price Shops (FPSs) to distribute commodities to low-income segments.However, distributing through FPSs has always seen problems of diversion and “leakages”. A high-powered committee appointed under Mr Shanta Kumar, Member of Parliament, estimates that 46.7% of goods distributed through FPSs were lost to “leakage”. Two models suggested in the Shanta Kumar committee report to arrest leakages, are: 1) direct benefits transfer; and 2) automation of distribution channel. In this note, we discuss savings that have accrued to the state of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana (partially) because of automation of FPSs. Based on the findings, we can divide savings (realised/disguised) into three broad types:

1. Savings due to one-time activity of de-duplication;

2. Recurring savings due to beneficiaries willingly not turning up to receive their entitlement; and

3. Savings due to inconvenience ― currently being calculated by states, but which should not be included. These savings are due to transaction denial owing to server failure and/or authentication failure; or closed shop.

Automation of the front-end distribution system in PDS results in very significant savings to the government. These savings justify the investment in deployment of automated systems. The one challenge that we foresee is that profitability of FPSs has come down drastically, as diversion of food grains has stopped. Our calculations show that profitability of an FPS outlet in the automated environment will be down to Rs.1,100 (USD 16.18) per month. Discussions with stakeholders shows that in the non-automated environment, FPS shops were making a profit of Rs.60,000-70,000 (USD 882-1,029) per month. State governments will have to relook and work out a commission structure that can ensure the long-term viability and sustainability of FPSs.

DBT in TPDS – A Mid-line Assessment: The Road Ahead Seems To Be Long

Government of India (GoI) implemented the National Food Security Act (NFSA) in 2013 to provide food and nutritional security to vulnerable households. Simultaneously, to make the system more efficient and to plug leakages, GoI requested States/Union Territories (UT) to implement a Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT). Two suggested methods were: 1) installation of point-of-sale (PoS) devices at fair price shops (FPSs) for biometric authentication of beneficiaries, and physical off-take of food grains, or 2) direct cash transfer to the beneficiary’s bank account. The UTs of Chandigarh, Puducherry, and Dadra & Nagar Haveli (DNH) opted for DBT through cash transfer. Chandigarh and Puducherry launched DBT in PDS in September 2015. However, DNH postponed the pilot roll-out due to upcoming local elections. To assess the performance of these pilots, MicroSave conducted a baseline assessment in August 2015, and a midline assessment in November 2015. We presented the baseline assessment in a separate note and this note looks at findings from the mid-line assessment. Progress in both the UTs of Chandigarh and Puducherry is chequered and needs streamlining before the pilot for DBT in PDS can be scaled up. On parameters such as access to market, availability of withdrawal points, and use of the subsidy payments, the pilot has done well in both UTs.

However, the pilot has highlighted the need for additional work on awareness – a recurring theme (see “Communication: The Achilles Heel of Direct Benefit Transfer – 1 and 2”) ― and grievance redressal. There are also challenges in terms of adequacy of subsidy amount and whether there is subsidy diversion by male beneficiaries in the household. In Chandigarh, FPS shops closed down after the pilot launch. However, not all beneficiaries have managed to enrol for DBT, due to requirements related to the opening of bank accounts and linking these to their Aadhaar numbers. Puducherry has seen similar challenges. The administration will have to look into this aspect, as exclusion can be detrimental to the overall success of the scheme.

Baseline Assessment for DBT in TPDS: Will This Small Step Become a Giant Leap?

Based on successful roll-out of subsidy transfers for cooking gas, directly into the bank accounts of beneficiaries, the Government of India in September 2015 announced Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) for PDS beneficiaries. We conducted assessments in August 2015, just before disbursement of the first tranche of cash transfers in lieu of subsidised food grains. This Note pertains to the findings of the baseline assessment. Despite many challenges, the situation was conducive for a pilot for DBT in lieu of food grains in Chandigarh and Puducherry. However, given the market infrastructure in Dadra and Nagar Haveli, it was best that the pilot was dropped; DNH lacks an alternative market and needs subsidised food grains through FPS. There are also other fundamental challenges to DBT in PDS. One of the most fundamental is the amount of money paid to beneficiaries in lieu of food grains. At present, PDS entitles low-income families to get wheat at Rs. 2 per kg, rice at Rs. 3 per kg and coarse grains such as bajra/ragi at Rs. 1 per kg. As against this, the government has fixed the DBT amount at 1.25 times the minimum support price (MSP), which is, in essence, the price at which the government procures food grains from farmers. Recipients are not happy with the amount of money received as DBT under PDS.

Real and Perceived Risk in Indian Digital Financial Services

The risks associated with digital financial services (DFS) are varied and a growing area of attention and assessment. At the same time, digital payments and broader digital financial services introduce added complexity, with new participants constantly entering the market, new products regularly introduced, and value-chain dynamics in constant flux.

In MicroSave’s recent research for the Omidyar Network, we covered all types of risks that customers and agents face. It is important to note that fraud is just one facet of risk. There is a growing body of literature on risks in DFS, and these concepts are largely related to customer protection issues. From a customer protection perspective, both Alliance for Financial Inclusion and SMART Campaign have defined risks and vulnerabilities in DFS.

Our research also explored risks from customer protection perspective. This involved going a step further than just listing risks that agents and customers face, and analysing the medium to long-term impact on the uptake and usage of DFS.

Our research also explored risks from customer protection perspective. This involved going a step further than just listing risks that agents and customers face, and analysing the medium to long-term impact on the uptake and usage of DFS.

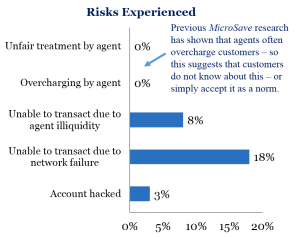

The risks and their ranking by customers (see graph) are not very different from the 16-country study conducted by CGAP. However, another risk that features prominently in India is ‘transaction data security’ or privacy of client account information. This mainly relates to agent-assisted transactions.

Most of the issues in India are operational in nature. Our qualitative research also shows that most significant risks perceived by the customers related to issues like network downtime, system and technology risks, agent unavailability, and agents lacking liquidity.

However, even these operational issues can have serious implications. Frequent service denial, incomplete and interrupted transactions, inaccessible funds, etc., leading to delay or loss of opportunity ― all negatively impact customers’ trust in DFS.

Agents face similar risks. Their key concern is also related to systems/technology and network downtime/outages while trying to serve their clients. We also explored four different types of risks individually in the research. These were:

- Account being hacked/compromised,

- Inability to transact due to network failure,

- Inability to transact due to agent liquidity issues, and

- Overcharging by the agent.

While (most) customers have not actually experienced these risks, the perception of risk has an effect on the usage and uptake of DFS.

Under the ‘Fraud Framework’, described in MicroSave’s ‘Fraud in Mobile Financial Services’ paper, India would still be classified under the “customer acquisition” stage.

This phase in India is led by government schemes like PMJDY and G2P payments. As a result, most risks rank low in terms of their occurrence. However, as the markets evolve and move to the “value addition” stage, different types of risks will evolve.

On the agent side, it is clear that poor commission is key ― both a bottleneck to growth and a driver of fraud. Field observations reveal that to maximise commissions, agents may commit fraud, or what agents call ‘workarounds’. Some frauds which often go unnoticed are

On the agent side, it is clear that poor commission is key ― both a bottleneck to growth and a driver of fraud. Field observations reveal that to maximise commissions, agents may commit fraud, or what agents call ‘workarounds’. Some frauds which often go unnoticed are

- Agents conducting round-tripping (cashing in and cashing out the same amount) transactions to earn higher commission;

- Splitting single big ticket transactions into multiple small transactions – again to maximise commission; and

- Agents overcharging customers to maximise earnings.

In response, financial service providers and agent network managers will need to:

- Contextualise risk management frameworks to the Indian context and according to the state of the evolution of the market

- Integrate this risk management framework into their operations and train agents accordingly

- Develop indicators for monitoring risks

- Regularly monitor risks and

- Develop risk-mitigation strategies

As part of this, providers and agent network managers will need to:

- Address the “hygiene factors” of system and agent reliability – see Solving Customer Service Issues in Digital Finance – Can Do, Must Do;

- Implement a comprehensive and formalised system of monitoring (something that has been largely absent to date – see Training, Monitoring & Support – Necessary, or An Opportunity To Cut Costs?

- Monitor agent performance, develop a system for warnings, censure and penal action, including termination; and

- Establish and enforce minimum disclosure and transparency requirements for product features, pricing, and terms of use.