Pakistan is easily one of the top five leading digital finance markets in the world; yet also certainly one of the least understood. Anyone striving to learn about it must first understand how the Over-the-Counter (OTC) methodology adopted in Pakistan works, as it operates uniquely compared to other markets, especially those where it is unregulated. Its dominance in Pakistan has greatly influenced how the market has developed, and the recently released Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) Pakistan 2014 report provides great insight into how the methodology had led to a fractured market and powerful agents.

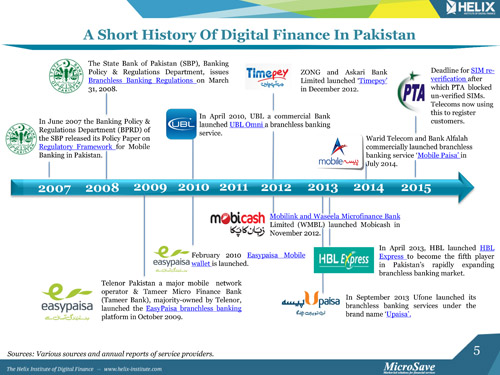

A Short History of DFS in Pakistan

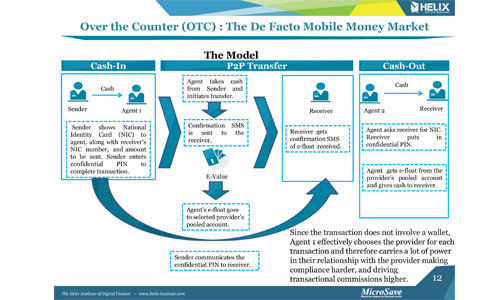

The telecommunications market in Pakistan in 2009 was quite competitive with five providers each holding significant market shares. This was when Telenor Pakistan (in partnership with Tameer Microfinance Bank) launched the first digital financial service, Easypaisa. However, they did not want to limit the potential user base to the 22% of mobile phone subscribers that used Telenor SIM cards so they led with a methodology called Over-the-Counter (OTC) in which transactions are executed by the agent at the outlet, as opposed to over a mobile wallet platform by the customer. Therefore, agents are able to conduct transactions for everyone as opposed to being limited to those carrying the specific SIM card of the provider.

OTC Makes it Easy to Get Customers but Very Hard to Keep Them

The OTC method meant that Easypaisa did not have to invest in convincing individuals to register for a mobile wallet and instead could just register agents and promote the use of the service at agent locations. While this surely helped catalyse growth rates in transactions, it also left the door open for other providers to follow suit. In an OTC market, neither the amount of SIM cards a provider has in the market, nor the amount of customers they have registered for digital financial services yield significant competitive advantages. Therefore, while the methodology allows providers with smaller market shares in the voice/banking business to potentially scale transactions quickly, it also means that being the first mover in the market is not necessarily an advantage.

The first mover (if they do a good job) actually lowers the barriers to entry for its competitors by conducting initial agent training and also funding the initial marketing campaigns that make the population aware of what the service offers. Therefore subsequent movers in the market have a much easier task as they can simply register already trained agents to provide services to already aware customers with relatively less investment. They just have to ensure that the service they offer is similar to that already on offer so that it is easily understood.

The Fractured & Volatile Market

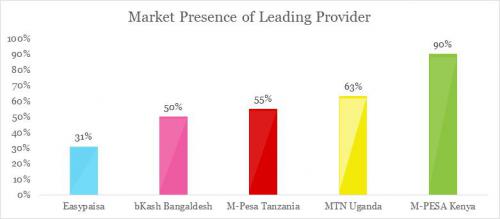

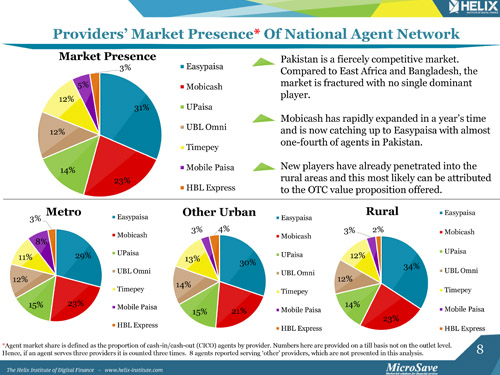

The aforementioned factors have lead the Pakistani market to become more fractured and volatile compared to the other leading digital finance markets studied by The Helix Institute—Uganda, Tanzania, Kenya and Bangladesh. The leading brand in Pakistan, Easypaisa has the lowest overall market presence compared to the market leaders in the other countries, meaning there a smaller magnitude of market dominance from a single provider.

Pakistan also has the most competitors in the market, with six providers that have five percent or greater market presence, whereas Bangladesh only had four when surveyed in 2014 and the East African markets all had three or less. This means that not only do market leaders have the smallest leads on their competitors in Pakistan, but they also have the most competitors to compete against.

Further, there is incredible volatility in the market share each provider controls in terms of transaction volumes and values, and in their individual market presence in terms of how many active agents they have offering their services in the market. Mobicash and Upaisa have managed to grow at incredibly robust rates, displacing providers that launched years before them because again the easy to adapt OTC method actually enables big telecoms to quickly convert their GSM retailers into digital finance agents..

Agents Decide which Service Provider a Customer Uses

The OTC methodology switches the location of the battlegrounds for market share from the customer (as seen in mobile wallet-based markets) to the agent. Again, this is because the service a customer uses is not determined by the SIM in their phone or the card in their pocket, but by which service provider the agent chooses to use to execute the transaction. The agent then has the power to tell a customer to use one provider over another for reasons like the customer’s preferred service provider is not working or is inferior for some reason. Therefore, instead of employing product innovation to win customers, Pakistan is subject to commission wars to win agents. Providers constantly have to manoeuvre each other to provide agents with enough commissions relative to competitors to have them consistently use their service as opposed to their competitors.

The Future

Over the years, as the competition has intensified, providers report investing higher percentages of revenues back into agent commissions, steadily decreasing their own margins and leaving them in the same position in the next month when they have to fight for an agent’s loyalty once again. It is the story of fractured markets and of powerful agents. However, in the beginning of 2015, the Pakistan Telecommunications Authority (PTA) asked all telecom providers to biometrically register all their SIM cards, and providers have been using this as an opportunity to also register customers for mobile-based wallets. While several million customers have been registered for wallets since the beginning of the year, the real challenge will be for providers to design products to deliver over this channel that will really interest customers.

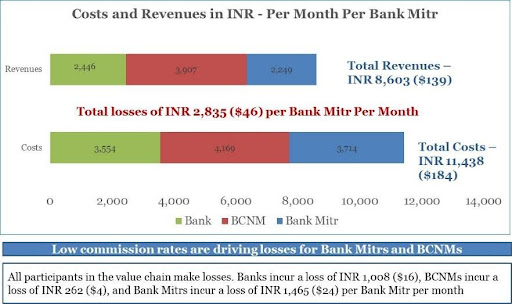

Bank Mitr networks in India have been weak, with a

Bank Mitr networks in India have been weak, with a