Saloni Tandon works with Inclusive Finance & Banking domain at MicroSave and has applied MI4ID approach on various projects like …., etc

Blog

MI4ID Training – Manoj Pandey

Manoj Pandey is Senior Analyst at MicroSave. In this video, he talks about application of MI4ID approach in projects like Designing a micro-pensions product in Cambodia to designing access to agriculture insurance solutions in Markets like Ethiopia

Understanding the Money Management Practices and Financial Exigencies of the Mass Market Customer

Understanding the Money Management Practices and Financial Exigencies of the Mass Market Customer

Customer Protection in Indian Digital Financial Services: Part 1: Recourse

There is growing concern about customer protection. This can be seen from initiatives such as Code of Conduct for mobile money players by GSMA, the update of the SMART Campaign’s client protection to create principles for DFS. These initiatives represent industry-wide commitments to build awareness, better practices, and standards that could contribute to strengthening customer risk mitigation in the financial inclusion space.

Customer protection plays a direct role in reducing risks faced by customers. It plays a major role in building and maintaining trust of customers in digital financial services.

MicroSave’s study for the Omidyar Network on customer protection, risk and financial capability in India tried to understand the extent to which customer protection practices were embedded into DFS offerings in India. The research examined the effectiveness of these customer protection practices and the ease with which customers and agents could access them.

The following sections discuss the important SMART Campaign Principles which are applicable here:

- Recourse: The grievance mechanisms available for customers and agents

- Transparency: How terms and conditions are communicated to customers and agents

- Data Privacy: How customers and agents safeguard their data (and money)

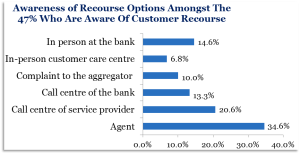

Only 47% of customers were aware of recourse options and their primary source of information was the agent. Low awareness of customer recourse can reduce customer trust in FSPs. Furthermore, it makes customers highly vulnerable and dependent on agents.

Even though experienced users have shown that they use the call centre more often than inexperienced users, overall awareness level is still very low.

The agent is the most important source of recourse options. Evidence in the FII research and CGAP country case studies confirms that DFS customers often look to agents to resolve problems. 98% of Indian customers say that the agent will be able to support them in case they face any risk in future. When compared globally, in Ghana, for example, 61% of mobile money users say they turn to an agent, and in Rwanda 52% report doing so (InterMedia, 2015). This highlights the emerging nature of DFS in India, where awareness levels are low and dependency on the agent is extremely high.

So what happens when customers have complaints about the agents?

Only half of customers say that they know what to do if they have problems with an agent. The research showed that customers prefer to discuss agent-related issues at the bank branch or by contacting the service provider’s call centre. A small percentage of customers complained about agent-related issues to the agent himself. This phenomenon could have two possible (though inter-related) explanations:

a) the agent is from the same community or from a nearby location, which results in high level of association with him/her; and

b) the absence of a proper recourse mechanism.

88% of customers believe that the recourse mechanism is efficient enough to resolve any issue faced by them. This could be a case of misplaced belief, as instances of risk have been low and, therefore, the need to actually access recourse has been limited to date.

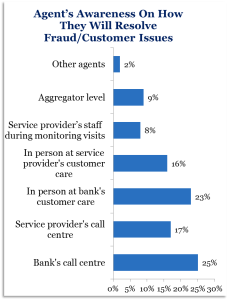

And what of agents’ ability to resolve problems?

While 79% of agents are aware of recourse options, only 24% of agents who faced problems actually used a recourse mechanism. This figure is disturbing since three-fourths of the agents didn’t even try to resolve problems, suggesting a broken system/process.

While 79% of agents are aware of recourse options, only 24% of agents who faced problems actually used a recourse mechanism. This figure is disturbing since three-fourths of the agents didn’t even try to resolve problems, suggesting a broken system/process.

As a proxy, this is also corroborated by the low use of call centres. The ANA India Research shows that only 52% of agents say that they know about call centre option to resolve queries.

Call centres can and should play an important role in customer service and protection in digital finance deployments. Given India’s world leadership in call centre management, it is to be hoped that the current situation will not persist for too long. That said, the pitifully slim margins for DFS providersmean that they will always be looking for opportunities to cut costs.

In the next blog in this series, we will look at Transparency and Privacy.

Crafting a Visual Identity for MI4ID

This is the story of how we created a visual identity for Market Insights for Innovation & Design (MI4ID). A signature approach to product development and innovation, MI4ID is the culmination of MicroSave’s two-decade journey to understand the lives of the low-income segment.

The MI4ID logo embraces MicroSave’s heritage while highlighting MI4ID’s vision and values. Through this story, we hope to inspire branding experts across the globe, while highlighting the pride of the teams that worked on it.

Design, Unleashed

We had to develop an instantly relatable, meaningful identity through the MI4ID logo. For this, we hired an external design consultancy. It recommended visualising the philosophy of MI4ID in a way that is impactful yet captures the values of MicroSave. At every step of the design process, we pushed ourselves until we were absolutely convinced about the visual representation of this unique approach.

At the core of MI4ID lies an openness to new ideas and new ways to tackle the persistent challenges in development. While brainstorming on the design, we discovered a single word that is at the core of MI4ID – ‘unbox’ – which links to ‘out-of-the-box’ thinking. We chose ‘unbox’ because MI4ID rises above the frames and stereotypes that colours one’s vision; because MI4ID is about free, unrestrained thinking; because MI4ID demystifies and explains things thoroughly, leaving nothing in the dark. The logo, therefore, needed to bring all these aspects to life.

At the core of MI4ID lies an openness to new ideas and new ways to tackle the persistent challenges in development. While brainstorming on the design, we discovered a single word that is at the core of MI4ID – ‘unbox’ – which links to ‘out-of-the-box’ thinking. We chose ‘unbox’ because MI4ID rises above the frames and stereotypes that colours one’s vision; because MI4ID is about free, unrestrained thinking; because MI4ID demystifies and explains things thoroughly, leaving nothing in the dark. The logo, therefore, needed to bring all these aspects to life.

Many Paths – One Goal

Based on our inputs, the consultant proposed 12 logos across three design themes. Each design comprised the logo unit, the baseline that explained the acronym, and a colour palette that linked MI4ID to its mother brand – MicroSave. One of the initial design themes positioned MI4ID as a creative thinker and used soft curves and a fluid, playful style to reflect the iterative yet flexible nature of the product. This theme saw a heavy use of interlinking elements and a modern, rounded aesthetic, as seen below.

While this was a great start, the design theme mimicked a style often seen in other creative logos. It needed to better reflect the mother brand and communicate experience, authority, and reliability. The design team, therefore, adopted a more conservative approach in the second theme. It envisioned an air of reliability and authority, yielding a handful of variations, as illustrated below.

This slightly formal theme, built on solid, vertical lines, spelt form and rigidity. This, however, did not work because while MI4ID is a rigorous approach, it is flexible and not prescriptive or dogmatic. The logo needed to communicate the harmonious tension between our founding pillars of market insights and innovations – distinct yet balanced perfectly. The designers developed a third theme based on the idea of modularity. Each element had equal weight and showed things in perfect balance. Two variations under this theme are listed below.

We selected the first option from this theme for further refinement.

Decoding the Logo

The design team provided a number of variants, from which we chose 2.2a. This variation combined rounded elements with solid geometrical lines. The combination of rectangles and circles added a subtle human element to the logo. This was especially important for us, as we have built MI4ID around human impulses and desires.

Yet the spacing and shapes in the logo needed fluidity. The designers acted on our cues and made subtle changes to the final shape of the logo, equalising the spaces between elements to arrive at the final design.

In this logo variant, the two ‘I’s mimic pillars and are in perfect symmetry at the top-right and the bottom-left. These identical pillars bring balance to the logo, representing a deep knowledge of empirical facts (insight) and the unleashing of creativity (innovation) – the two hallmarks of MI4ID. The logo represents the coming together of diverse elements in a cohesive whole.

The MI4ID logo uses just two colours. The blue hue reflects MicroSave and depicts trust, dependability, experience, and wisdom. The hints of yellow add a spark of energy and optimism. The consistent size and spacing of each element help guide the movement of the eye.

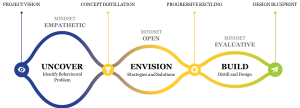

The dynamic curve of the letter D mirrors our in-house process of rapidly transforming ideas to market-ready prototypes. The spaces between the elements reveal the distinct, multidisciplinary phases in the MI4ID process. While each phase can exist independently, they can combine and be adapted to suit our clients’ needs. Each element contributes to the final outcome, and nothing is left out.

The flow of the elements shows the seamless way in which our process can shift from research to design for our clients. Seen from left to right, the MI4ID logo charts the journey from insights to action, which forms the beating heart of our signature approach.

The flow of the elements shows the seamless way in which our process can shift from research to design for our clients. Seen from left to right, the MI4ID logo charts the journey from insights to action, which forms the beating heart of our signature approach.

Where Does It Take Us?

The MI4ID logo represents our dynamism to bring about positive change. It showcases the seriousness with which we regard every assignment. While we are meticulous and systematic in everything we do, we retain creativity and encourage out-of-the-box ideas from everyone involved in an assignment.

For us, the MI4ID logo is more than just an elegant marque. It is a symbol of our rigorous research methods, perfected over many years. It reinforces MicroSave’s position as an organisation that is poised to play a leading role in solving the persistent development challenges facing millions worldwide – from designing digital financial services for the mass market to optimising agricultural value chains; from helping refugees to addressing the enormous challenges posed by climate change; and much more.

Crafting a visual identity for MI4ID

This is the story of how we created a visual identity for Market Insights for Innovation & Design (MI4ID). A signature approach to product development and innovation, MI4ID is the culmination of MicroSave’s two-decade journey to understand the lives of the low-income segment.

The MI4ID logo embraces MicroSave’s heritage while highlighting MI4ID’s vision and values. Through this story, we hope to inspire branding experts across the globe, while highlighting the pride of the teams that worked on it.

Design, Unleashed

We had to develop an instantly relatable, meaningful identity through the MI4ID logo. For this, we hired an external design consultancy. It recommended visualising the philosophy of MI4ID in a way that is impactful yet captures the values of MicroSave. At every step of the design process, we pushed ourselves until we were absolutely convinced about the visual representation of this unique approach.

At the core of MI4ID lies an openness to new ideas and new ways to tackle the persistent challenges in development. While brainstorming on the design, we discovered a single word that is at the core of MI4ID – ‘unbox’ – which links to ‘out-of-the-box’ thinking. We chose ‘unbox’ because MI4ID rises above the frames and stereotypes that colours one’s vision; because MI4ID is about free, unrestrained thinking; because MI4ID demystifies and explains things thoroughly, leaving nothing in the dark. The logo, therefore, needed to bring all these aspects to life.

Many Paths – One Goal

Based on our inputs, the consultant proposed 12 logos across three design themes. Each design comprised the logo unit, the baseline that explained the acronym, and a colour palette that linked MI4ID to its mother brand – MicroSave. One of the initial design themes positioned MI4ID as a creative thinker and used soft curves and a fluid, playful style to reflect the iterative yet flexible nature of the product. This theme saw a heavy use of interlinking elements and a modern, rounded aesthetic, as seen below.

While this was a great start, the design theme mimicked a style often seen in other creative logos. It needed to better reflect the mother brand and communicate experience, authority, and reliability. The design team, therefore, adopted a more conservative approach in the second theme. It envisioned an air of reliability and authority, yielding a handful of variations, as illustrated below.

This slightly formal theme, built on solid, vertical lines, spelt form and rigidity. This, however, did not work because while MI4ID is a rigorous approach, it is flexible and not prescriptive or dogmatic. The logo needed to communicate the harmonious tension between our founding pillars of market insights and innovations – distinct yet balanced perfectly. The designers developed a third theme based on the idea of modularity. Each element had equal weight and showed things in perfect balance. Two variations under this theme are listed below.

We selected the first option from this theme for further refinement.

Decoding the Logo

The design team provided a number of variants, from which we chose 2.2a. This variation combined rounded elements with solid geometrical lines. The combination of rectangles and circles added a subtle human element to the logo. This was especially important for us, as we have built MI4ID around human impulses and desires.

Yet the spacing and shapes in the logo needed fluidity. The designers acted on our cues and made subtle changes to the final shape of the logo, equalising the spaces between elements to arrive at the final design.

In this logo variant, the two ‘I’s mimic pillars and are in perfect symmetry at the top-right and the bottom-left. These identical pillars bring balance to the logo, representing a deep knowledge of empirical facts (insight) and the unleashing of creativity (innovation) – the two hallmarks of MI4ID. The logo represents the coming together of diverse elements in a cohesive whole.

The MI4ID logo uses just two colours. The blue hue reflects MicroSave and depicts trust, dependability, experience, and wisdom. The hints of yellow add a spark of energy and optimism. The consistent size and spacing of each element help guide the movement of the eye.

The dynamic curve of the letter D mirrors our in-house process of rapidly transforming ideas to market-ready prototypes. The spaces between the elements reveal the distinct, multidisciplinary phases in the MI4ID process. While each phase can exist independently, they can combine and be adapted to suit our clients’ needs. Each element contributes to the final outcome, and nothing is left out.

The flow of the elements shows the seamless way in which our process can shift from research to design for our clients. Seen from left to right, the MI4ID logo charts the journey from insights to action, which forms the beating heart of our signature approach.

Where Does It Take Us?

The MI4ID logo represents our dynamism to bring about positive change. It showcases the seriousness with which we regard every assignment. While we are meticulous and systematic in everything we do, we retain creativity and encourage out-of-the-box ideas from everyone involved in an assignment.

For us, the MI4ID logo is more than just an elegant marque. It is a symbol of our rigorous research methods, perfected over many years. It reinforces MicroSave’s position as an organisation that is poised to play a leading role in solving the persistent development challenges facing millions worldwide – from designing digital financial services for the mass market to optimising agricultural value chains; from helping refugees to addressing the enormous challenges posed by climate change; and much more.