Equity Bank’s introduction of the thin SIM under the Equitel brand is an important development for the Kenyan financial market as it brings customers more choice in terms of providers, and will hopefully push product innovation further in a market that has had trouble evolving beyond payments. We believe that to really make digital finance daily relevant for the mass market, benefits like free money transfers, and access to credit on the mobile phone will be key drivers, and that excites us about Equitel.

Equity Bank’s introduction of the thin SIM under the Equitel brand is an important development for the Kenyan financial market as it brings customers more choice in terms of providers, and will hopefully push product innovation further in a market that has had trouble evolving beyond payments. We believe that to really make digital finance daily relevant for the mass market, benefits like free money transfers, and access to credit on the mobile phone will be key drivers, and that excites us about Equitel.

However, for these benefits to be realized, Equity will need to get enough people on its system so it can have more control over the pricing, and that involves a massive registration campaign, and making the services simple and easy to use for customers. Equity’s major marketing campaign has focused on free money transfers, however, these are only from Equity accounts to other Equity accounts.

Transfers to or from other providers (like M-PESA or other banks) incur the charges of the other provider, and a small fee from the switch. This was made clear by the recent increase in Safaricom’s price of transfers that negatively impacted the value proposition offered by Equity Bank. While Safaricom had to temporarily delay the increase until December of this year, the customers have been made aware of the vulnerabilities of the system to price increases from payment service providers.

The obvious solution to this problem is to register more customers, so that they are more likely to be making transfers within the Equity system, where Equity can control the price, but that is a very difficult task, and may take a long time. In 2014 Intermedia found that only 21 per cent of Kenyan adults (~5.6 million) have active bank account (on a 90-day active usage basis). Equity reports the leading position in the Kenyan market with over half of banked population as its customers. While this is a very strong position in the banking sector, in the digital financial services Equity Bank must increase registrations to create a strong network effect, since it now more directly competes with M-PESA, which reports 13.9 million active customers on a 30-day basis.

After having our team register and trial the service, we discussed our experiences and offer our top five pieces of advice to increase the potential for Equity to scale quickly and disrupt the digital finance market in Kenya.

1. Registration processes can be streamlined: The basic requirement for a thin SIM is an Equity Bank account, which can be opened on the handset, however, people still need to visit an Equity Branch to show further documents, and where a specially trained staff can install the thin SIM on top of your existing SIM. This process took our team one to two hours each. Equity Bank should streamline the process of account opening, and it seems that more staff training on how to register customers would be a great area of focus.

In addition, Equity Bank may look at expanding the places where people can access and install thin SIM. As of now, users can only access one of the 166 bank branches during the branch opening hours only. While there have been some registration drives already, more highly advertised ones might help with this.

Streamlining the process of enrolment and installation of thin SIM and augmenting the number of places where the thin SIM can be procured and installed will mean more aggressive growth in the number of thin SIM users for Equity Bank. We should remember that M-PESA took about 10-15 minutes per customer to register, and the registration service was offer by M-PESA’s tens of thousands of agent outlets, open ten to twelve hours a day, six to seven days a week.

2. Registration costs can be made more enticing: The normal Equitel SIM card is basically free, as the cost for the SIM 50KSH (~US$0.50) is reimbursed as airtime on the phone. However, thin SIM costs 500 KSH (~US$5) and it comes with 200KSH (~US$2) of airtime. While Equitel has lowered this price from the original 600KSH (US$6) proposed, people still might not see the additive value of thin SIM as they already have SIM cards, which provide them with GSM, money transfer and banking services. In addition, an average Kenyan adult only earns about US$8.50 per day (based $3,100 yearly per capita GDP [PPP]). Thus, the cost represents a significant barrier to entry for the service, and lowering it may significantly increase enrolment.

3. Allay the perceptual security concerns of users: Equity Bank’s foray to thin SIM was stalled by Safaricom’s allegations on security concerns of a third party being able to intercept data from the primary SIM upon which the thin SIM is attached. Equity Bank won the case in the court; however, Equity Bank still needs to ensure it has won the case in the minds of Kenyans.

The thin SIM is unlike an NFC tag placed as a sticker on the back of the card. It is installed over the contact points of the existing SIM, so that it appears that any data going to the existing SIM passes directly through the thin SIM (even if it may be switched-off). While this is a perception issue, that still might be enough to deter some cautious customers. Further, as users themselves cannot remove the thin SIM, but will have to use the services of trained professional from the bank branch, it may deter people from making such a commitment if they have even an iota of doubt related to security of their data.

4. Thin SIM usage may be made more convenient for the users:One of the most alluring benefits of the thin SIM is that you do not have to give-up or even remove your existing SIM. With the thin SIM riding over the existing SIM, only one line can be used at any given time. This means that if someone calls the user on the existing SIM (your main line) while the thin SIM is activated, the user will not be able to receive the call.

To change between the existing SIM and the thin SIM, the user has to restart the phone or use a (rather long) short code (076300), which did not always work for us. The risk is that thin SIM users will only activate it when they want to make a money transfer to an Equity account, and since their contacts are more likely to call them on their existing line, they will have that one activated at all other times. Shortening the short code so it is easier to remember, and ensuring it works flawlessly will help this, and offering discounts on GSM services may help to get more people using the SIM for voice and SMS as well.

5. Monitor Normal Equitel Usage Closely: Equity also offers normal SIM cards beyond the thin SIM option. It should monitor the sales and usage of these SIMs carefully, and since these SIMs were launched well before the thin SIM there is a lot more usage of them and a lot more data to look at. Looking at our four recommendations above, three are circumvented by use of the normal SIM (registration streamlining still applies). The major con of the normal SIM is it must be switched in and out of a handset, or the customer would have to have a dual SIM handset or multiple handsets. While this seems burdensome, this is actually common in many markets, especially ones where competition on GSM is especially fierce, like neighboring Tanzania.

Using Intermedia’s The Finclusion Data Centre, we calculate that 29% of Kenyans that have a SIM card already own more than one, so this might not be such a burden for people after all. Specifically, Equity should monitor the relative growth rate of the normal SIM registration versus the thin SIM, but also usage of it, in terms of activation time per customer, and usage per customer for GSM and money transfer. It would also be interesting to look at user segmentation to see if this solution might be more popular with certain demographics like rural clients, and target marketing accordingly.

Equity Bank’s launch of Equitel on July 20, 2015 is representative of the aggressive drive banks have shown in Kenya to activate tens of thousands of agents across the country, and The Helix Institute 2014 Kenya Country Report clearly shows they are gaining ground. They are now firmly competing in the mobile payments space that Safaricom’s M-PESA has pioneered, while also trying to drive the market forward to its next evolution with more value-added financial services that people need. For Equitel the next step in this direction should be some product refinements as highlighted above. These are normal with any new digital product that launches quickly, and will need to augment their offerings according to initial customer feedback. The real test still remains for Equity to address these types of issues effectively and win enough customers to really be a disruptive force in the Kenyan market.

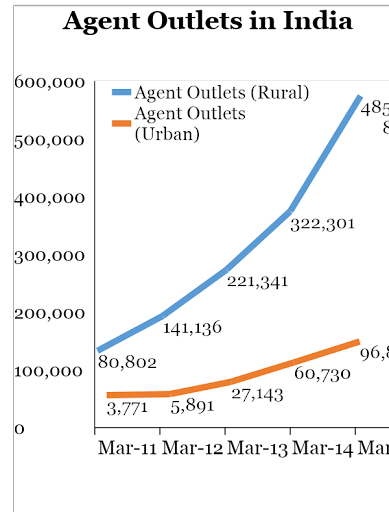

Despite this, the number of agents available in India has continued to grow — in both rural and urban areas. Given India’s sheer size, it is perhaps unsurprising that the number of agent outlets is considerable. Kenya has around 100,000 agent outlets; India (despite its faltering efforts at digital financial inclusion) has nearly six times this number. The annual growth rate of Indian urban and rural agent outlets remains in the range of 50%-60%.

Despite this, the number of agents available in India has continued to grow — in both rural and urban areas. Given India’s sheer size, it is perhaps unsurprising that the number of agent outlets is considerable. Kenya has around 100,000 agent outlets; India (despite its faltering efforts at digital financial inclusion) has nearly six times this number. The annual growth rate of Indian urban and rural agent outlets remains in the range of 50%-60%. However, two years later, 54% of the agents were “transaction ready” (and this rose to 79% by mid-2015) and were on average earning a gross revenue of Rs. 2,724 (US$42) per month (this rose by 45% to Rs. 3,951 or US$61 per month by mid 2015)

However, two years later, 54% of the agents were “transaction ready” (and this rose to 79% by mid-2015) and were on average earning a gross revenue of Rs. 2,724 (US$42) per month (this rose by 45% to Rs. 3,951 or US$61 per month by mid 2015)

Additionally, the SFBs will require

Additionally, the SFBs will require

.png)