Over the last four years, as part of the Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) project, we have interviewed more than 34,000 agents from over 40 leading providers of digital financial services (DFS) across 11 countries in Asia and Africa.

So what did we learn?

Agent Dedication and Exclusivity is Declining

We see a general trend towards agents running a DFS agency as an add-on to other existing businesses (non-dedication) and working for more than one provider (non-exclusivity). While the trend is most pronounced in Tanzania and Pakistan (see Figures 1 and 2). In Bangladesh, on the other hand, third party models have emerged.

At the same time, many providers see their agent networks as a source of differentiation from the competition and direct control over the agent channel. Our data confirms that agents trained and monitored by their providers perform significantly better than those left to their own devices (see Training and Monitoring Can Improve Agent Performance below).

So, while the move towards shared 3rd party agent networks seems an obvious next step to containing costs of platform management and maintenance, and of agent training, management and monitoring; as well as improved liquidity management (particularly in fully interoperable environments), there are limited signs of this emerging in many markets. In some markets regulations also limit the potential for 3rd party shared agent networks because regulators want to be able to hold a regulated financial institution accountable for agent performance.

Ultimately, providers should compete on product rather than channel. So we may see the emergence of a few exclusive sales agents working for specific providers to sell products, open accounts and conduct larger transactions. These would then be complemented by large numbers of shared agents servicing a range of providers by conducting small cash in/out transactions.

NOTE: ANA surveys were conducted in 2013 in Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania; in 2014 in Bangladesh, Kenya, Pakistan, and India; in 2015 in Zambia,Tanzania, Uganda and Senegal; in 2016 in Bangladesh and in 2017 in Pakistan.

NOTE: ANA surveys were conducted in 2013 in Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania; in 2014 in Bangladesh, Kenya, Pakistan, and India; in 2015 in Zambia,Tanzania, Uganda and Senegal; in 2016 in Bangladesh and in 2017 in Pakistan.

Insight: Service and support to agents can be a key success driver and differentiator – but 3rd party model/outsourced services may be the way to go in the future, at least for cash in/out transactions.

Insight: Service and support to agents can be a key success driver and differentiator – but 3rd party model/outsourced services may be the way to go in the future, at least for cash in/out transactions.

Inability to Transact Remains a Problem

Many agents report experiencing periods when they are unable to transact, be it due to network interruptions or system downtime. Service downtime not only causes inconvenience, it also erodes trust. Service downtime is particularly frustrating for customers, who feel that they are unable to access their money and, in some cases, complain of missing important opportunities or deadlines as a result. It also often results in customers leaving money with agents to complete the transaction when the system is back up, which raises fraud risk.

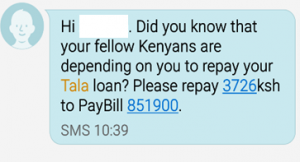

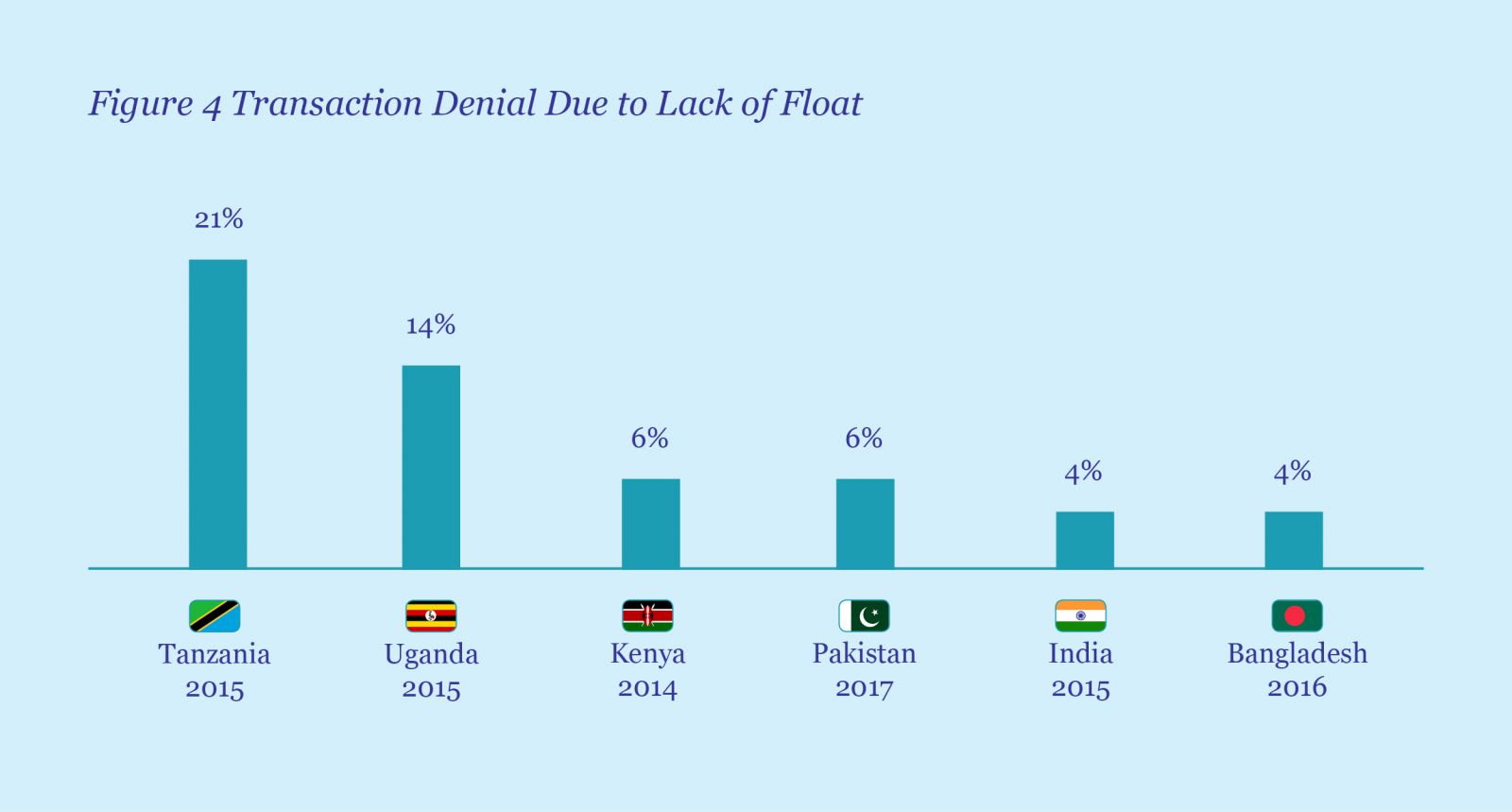

Furthermore, too many transactions are still being denied due to liquidity management challenges. Agent illiquidity may also mean lost access to money or necessitate splitting of transactions and thus incurring higher transaction fees and customer time[1] These inconveniences and supplementary costs undermine user trust (who will allocate less money to the system and conduct fewer transactions) and non-users (who may avoid DFS for fear of not being able to access their money when they need it).

Furthermore, too many transactions are still being denied due to liquidity management challenges. Agent illiquidity may also mean lost access to money or necessitate splitting of transactions and thus incurring higher transaction fees and customer time[1] These inconveniences and supplementary costs undermine user trust (who will allocate less money to the system and conduct fewer transactions) and non-users (who may avoid DFS for fear of not being able to access their money when they need it).

Moreover, every transaction denied for want of float, reduces commission income for the agent in an operating environment where they already struggle to make adequate profits (see Agent Viability Remains a Problem below).

Insight: Trust continues to be eroded. Providers with reliable platforms and reliable liquidity management systems will carry the day.

Approaches to Liquidity Management Are Evolving

Providers are beginning to use creative approaches to respond to liquidity management challenges, including:

– Dedicated rebalancing counters at banks to provide agents faster service;

– Liquidity “runners” to deliver liquidity in the form of both cash and e-float;

– Credit lines/overdraft facilities for float;

– The use of analytical tools to predict demand; and

– Providing in-depth liquidity management training to Master Agents.

Insight: We still need more solutions for liquidity management, especially to get cash to rural areas. Advanced data analytics, the “uberisation” of agents and creating better digital ecosystems to keep money digital can all help.

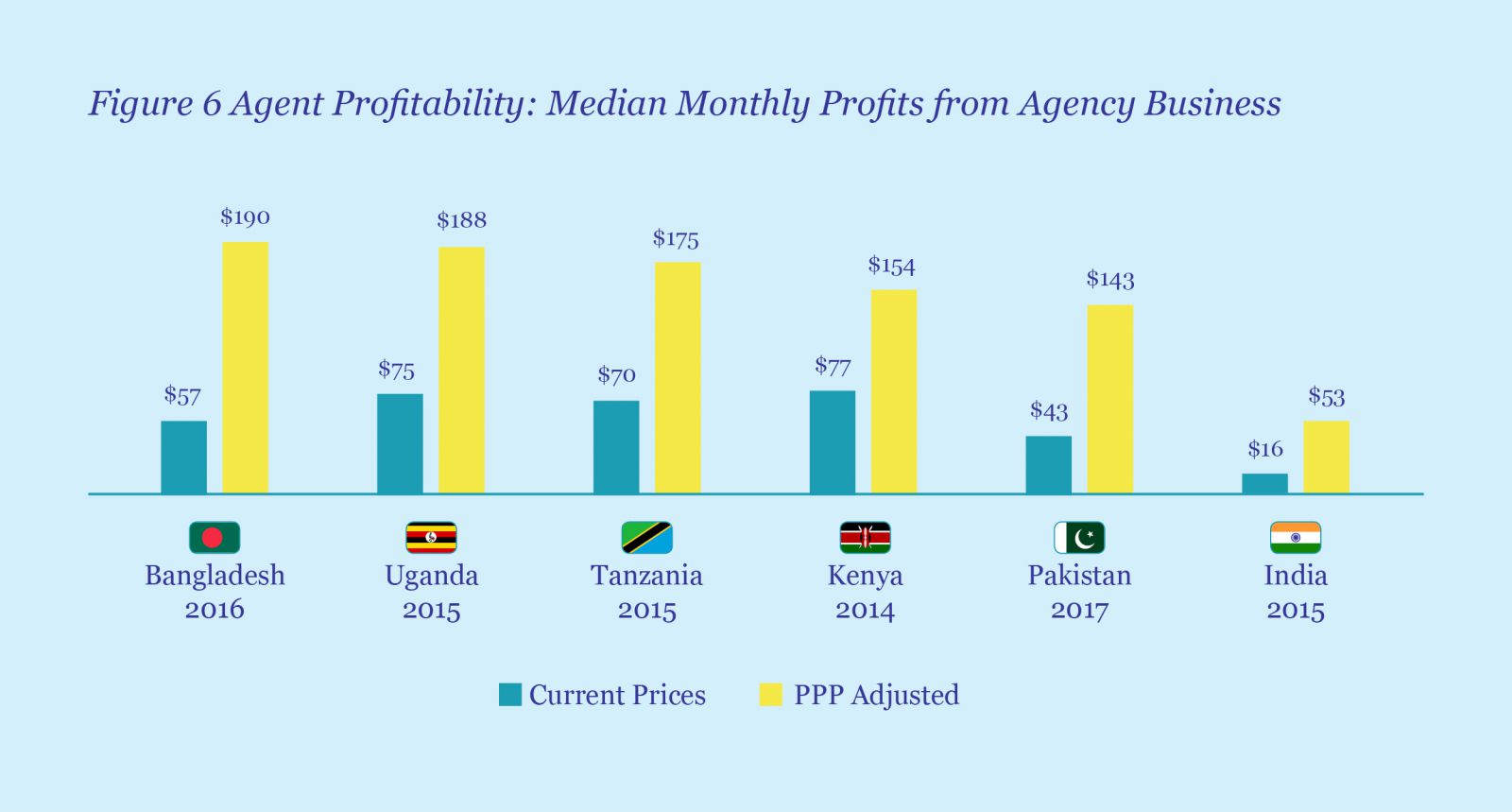

Agent Viability Remains a Problem

Profits from the DFS agency business are modest, between US$143 and US$190 per month, (adjusted for cost of living differences). The highest agent profits were reported in two markets plagued by illicit OTC transactions, frequently performed by agents for an unofficial, unauthorised fee. Unauthorised fees or overcharging is common, enabled by lack of transparency (many agents do not display approved or current pricing schedules for their services). As a result, customers are unsure of service fees and often convinced that they are being over-charged, undermining trust and reducing service uptake and usage.

Unauthorised fees, of course, create real additional costs for customers but are increasingly accepted as part of the fee-for-service – particularly where agents are conducting OTC transactions and thus reducing the risk of sending money to the wrong number. Given some of the losses that can result from sending money to the wrong number, perhaps we should not be surprised that people are willing to pay a premium to protect themselves against this risk.

However, this clearly a suboptimal solution for both consumers (who confine themselves to agent-assisted transactions, limiting the opportunities for cross selling additional products and services), or the provider (which becomes dependent on agents and thus limits profitability) in the long run. Safaricom has sought to address this with the Hakikisha system that enables M-PESA customers to stop erroneous transactions within a window of 25 seconds and allows up to five such instances per day

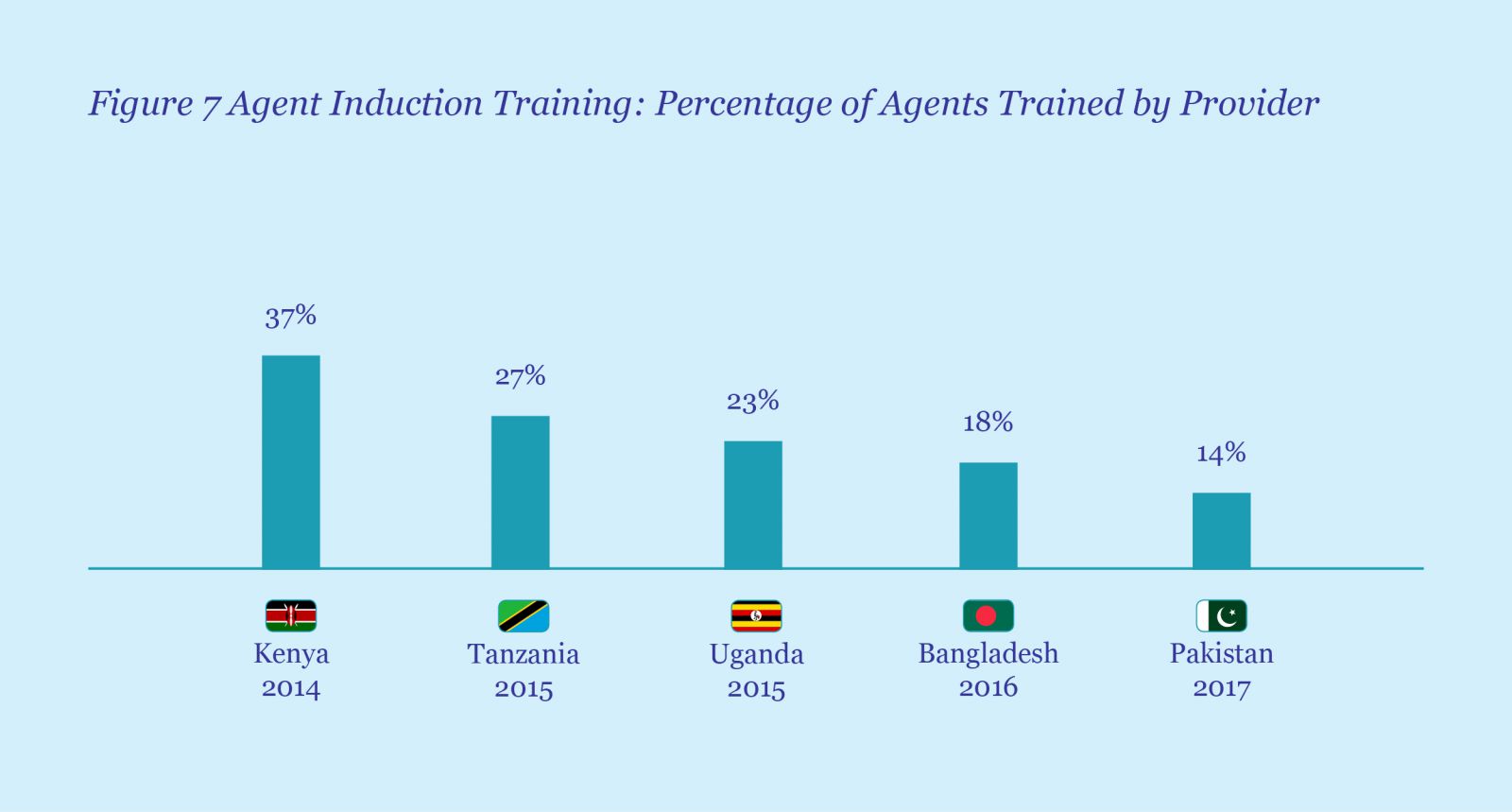

Agent Training and Monitoring Associated with Better Performance

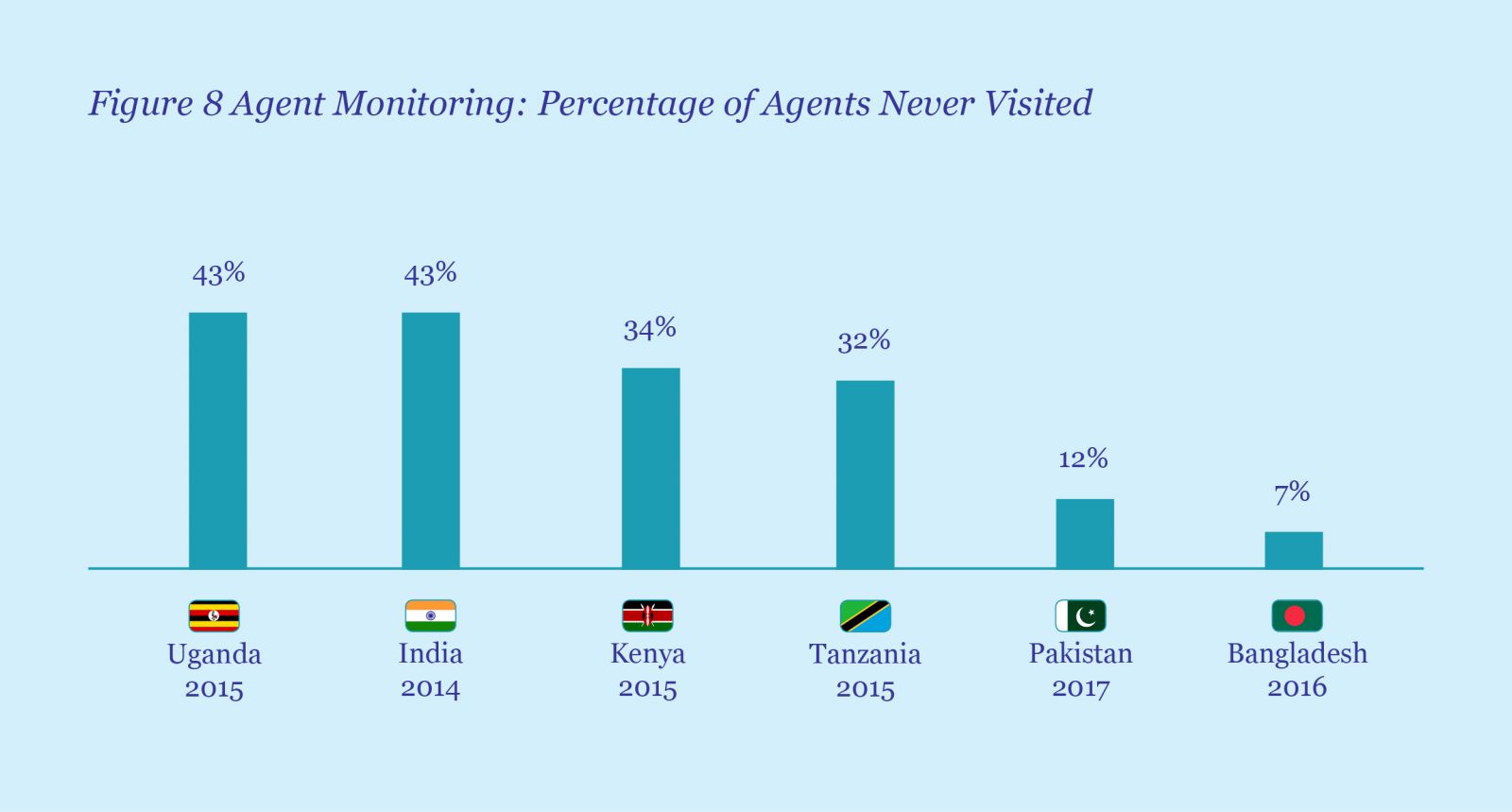

Providers tend to delegate induction training to Master Agents and third parties – only a minority of agents report being trained directly by the provider. Likewise, too many agents are being left to their own devices and never receive monitoring or support visits. This is likely to suppress their profitability. As a recent Harvard Business School research demonstrated, the presence of tariff sheets increase demand by over 12%, while agents’ ability to answer a difficult question about mobile money policy increases demand by over 10%.

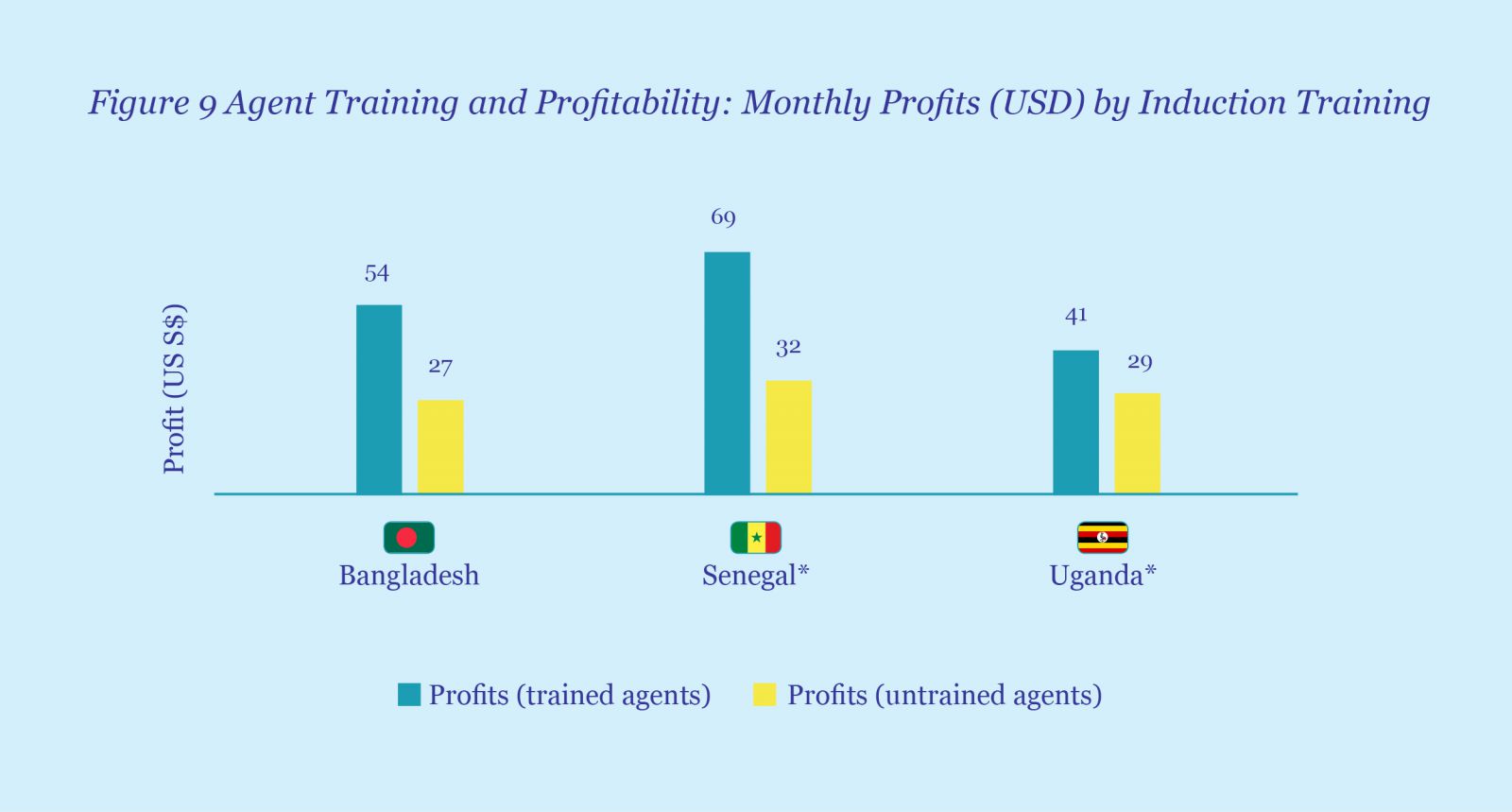

We have seen some evidence that training is associated with improved compliance and increased profitability. This association is clear in Bangladesh, Senegal and Uganda, but much less pronounced in other countries surveyed under ANA programme.

Insight: Training may be associated with better compliance, transaction volumes and profitability of agents, yet providers continue to outsource this function.

Robbery and Fraud are Increasing

Agents are struggling in the face of rapidly growing problems with robbery and fraud. This is a challenge that needs concerted and coordinated efforts to resolve. Providers and agents are beginning to address this problem, but more can be done. In our expert group meeting, providers, software platform vendors and consultants recommended a three-pronged approach: 1. training of agents; 2. the monitoring of fraud trends and proactively informing agents; and 3. collaborative fraud monitoring and reporting frameworks. A recent in-depth analysis of options to address the growing scourge in Uganda highlighted five different fronts on which fraud can be tackled.

Insight: Insecurity and fraudulent activities are growing – this could increase agent churn and to further undermine trust in digital financial services.

The ANA surveys have given us deep insights into the behaviour and evolution of agents across 11 countries. Many of the issues and challenges are now well-known, and the surveys quantify them in ways that have not been previously done. As a result of these surveys and the associated training, many providers have taken important steps to improve the quality of their agent networks, but much remains to be done. Agent networks remain the most costly and complex part of any DFS deployment, and successful providers are invariably those that get this crucial piece of their business right.

| MicroSave’s Agent Network Accelerator programme has conducted research on agent networks in 11 countries – Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Nigeria, India, Indonesia, Bangladesh, Pakistan, Zambia, Senegal and Benin.

The surveys deliver cutting edge knowledge and data designed to help leading providers overcome the cost and complexity of building sustainable cash-in/cash-out (CICO) networks. We produce country and provider reports, The data and reports power The Helix training curricula. Managed by MicroSave, the ANA surveys have been funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, UNCDF, Karandaaz and FSD-Uganda. |

[1] However, it is important to remember that service downtime and illiquidity also occur with, and are tolerated by customers of, ATM-based systems.

3. Loan application processes: Many SMS-based and USSD-based digital credit systems make it almost too easy to access credit, thus potentially encouraging frivolous applications for credit. This, may need management through behavioural nudges – for example to encourage the potential borrower to view the terms and conditions, or to reaffirm the need for the loan after a nominal “cooling off” period. In contrast most app-based systems require the user to

3. Loan application processes: Many SMS-based and USSD-based digital credit systems make it almost too easy to access credit, thus potentially encouraging frivolous applications for credit. This, may need management through behavioural nudges – for example to encourage the potential borrower to view the terms and conditions, or to reaffirm the need for the loan after a nominal “cooling off” period. In contrast most app-based systems require the user to

Makena, 37, runs a grocery shop in Igoji town. She is married and has four children. At any given month, she services over three digital loans in addition to traditional loans. Currently, she uses M-Shwari for emergencies and to boost her business, KCB M-Pesa for ease of consumption and Equitel to pay school fees. Occasionally, she uses Airtel Kopa Cash for sports-betting. She also has an $8,000 land loan from Cicido SACCO and another one from Equity Bank, which was used to restock her shop after it was looted. She usually repays late, but right before being negatively listed to ensure she can borrow again. ‘I prioritise [repaying] the Sacco loan as opposed to digital loans due to the huge penalties on default imposed by the Sacco. In some cases, they take your personal assets.’

Makena, 37, runs a grocery shop in Igoji town. She is married and has four children. At any given month, she services over three digital loans in addition to traditional loans. Currently, she uses M-Shwari for emergencies and to boost her business, KCB M-Pesa for ease of consumption and Equitel to pay school fees. Occasionally, she uses Airtel Kopa Cash for sports-betting. She also has an $8,000 land loan from Cicido SACCO and another one from Equity Bank, which was used to restock her shop after it was looted. She usually repays late, but right before being negatively listed to ensure she can borrow again. ‘I prioritise [repaying] the Sacco loan as opposed to digital loans due to the huge penalties on default imposed by the Sacco. In some cases, they take your personal assets.’