The Helix Institute of Digital Finance is excited to release our new paper by Mike McCaffery and Annabel Schiff, “Finclusion to Fintech” which is designed to help fintech innovators understand the unique money management strategies used by low-income people in the developing world. The paper is aimed to serve as a tool to help fintech providers design appropriate financial products that underserved individuals will want to use on a regular basis. To understand the needs and desires of low-income people, the paper presents detailed insights from 15 years of financial inclusion research, along with the latest industry data. In addition, through illustrative examples, informal money management techniques are compared to formal techniques used by high-income people. To read through the report, please click here.

Blog

Interoperability – A Regulatory Perspective

Basis great inputs and discussions from Amrik Heyer, FSD Kenya, Stephen Mwaura former Head of Payments, Central Bank of Kenya, Uma Shankar Paliwal, Former Executive Director, RBI, Dennis Njau, Head of Channels, Kenya Commercial Bank, Gang Chai, Payment Policy Manager, Central Bank of Nigeria and Johnah Nzioki from Eclectics.

In a recent workshop organised by MicroSave’s The Helix Institute, leading DFS industry players including providers, regulators, aggregators, and technology providers, came together to deliberate on innovative ways to address the key challenges facing agent networks. They divided into three groups to look at the key issues in the context of: 1. policy and regulation; 2. strategy and market evolution; 3. operations.

The policy and regulation group noted that:

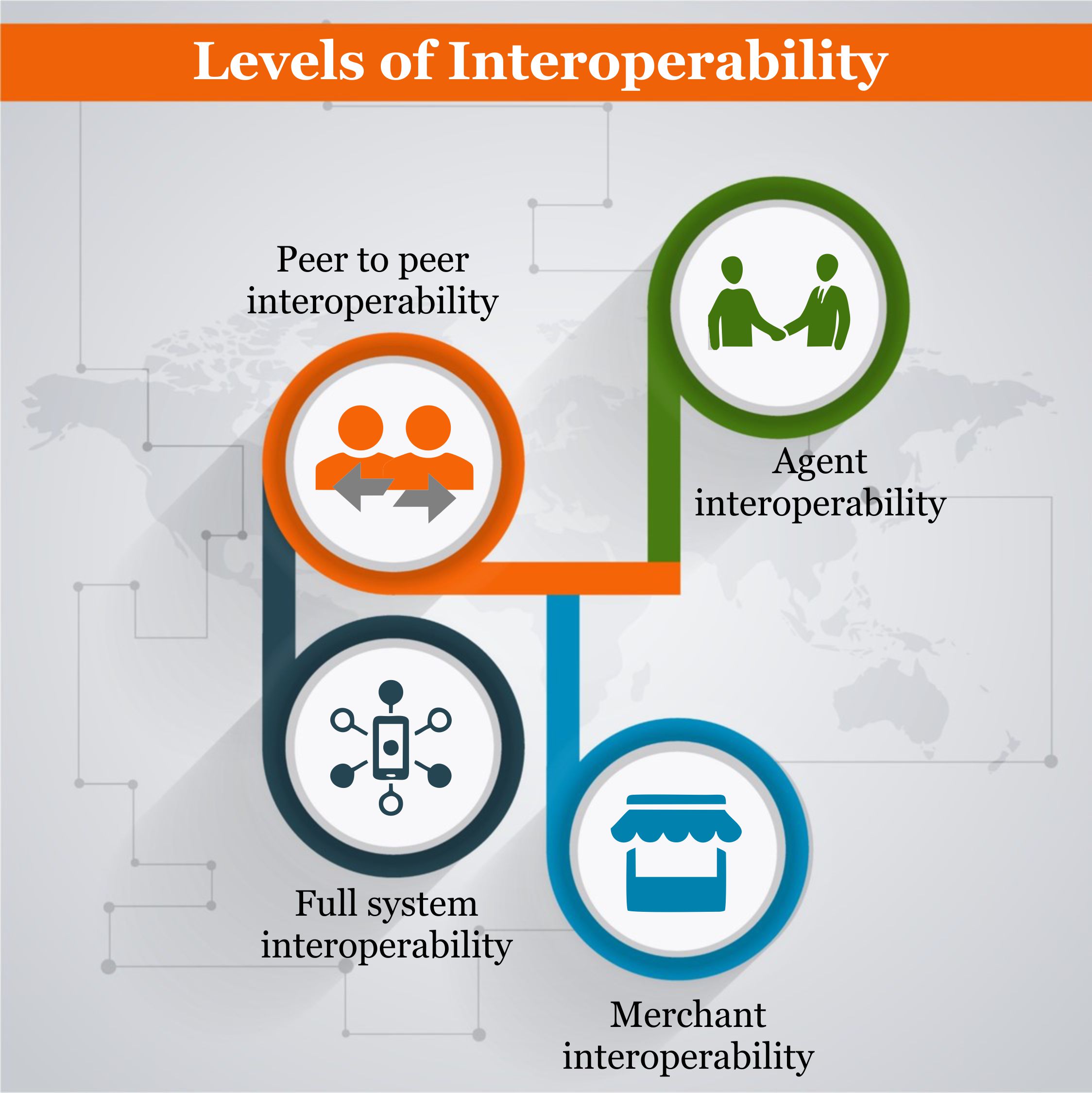

Countries around the world are at different stages of payment system evolution. There are different  levels of interoperability as defined by the Better Than Cash Alliance. From peer to peer interoperability, to agent interoperability, to merchant interoperability and full system interoperability. Peer to peer interoperability sees individual institutions connecting one on one through individual connections; agent interoperability, sees agents able to operate transactions between providers; merchant interoperability where merchants can accept payments form any provider; and full systems interoperability sees institutions, banks, mobile financial service operators or both connecting to a common platform or switch, thereby facilitating transactions.

levels of interoperability as defined by the Better Than Cash Alliance. From peer to peer interoperability, to agent interoperability, to merchant interoperability and full system interoperability. Peer to peer interoperability sees individual institutions connecting one on one through individual connections; agent interoperability, sees agents able to operate transactions between providers; merchant interoperability where merchants can accept payments form any provider; and full systems interoperability sees institutions, banks, mobile financial service operators or both connecting to a common platform or switch, thereby facilitating transactions.

Interoperability offers benefits for the wider ecosystem – these include: wider adoption; higher transaction volumes; and greater velocity of money in the ecosystem. From consumers’ perspective, interoperability means more convenient and efficient services. For regulators and policy makers this translates to reduction in expensive cash in circulation; expansion of the formal financial economy and a direct impact on advancing financial inclusion.

However, countries have different paths to interoperability, driven partly by the circumstances in their market and partly by regulatory philosophy. Some espouse competition on the basis of products and services provided by individual institutions, rather than on channels, which everyone needs to use. This view underpins the shared agent initiative in Uganda, for example. For others like the Better Than Cash Alliance, interoperability is a key aspect payment system evolution.

In the case of Rwanda a national policy on interoperability sought to: create a cash-lite society, encourage financial inclusion, and promote payment system efficiency. The goal for in interoperability was to: improve productive efficiency; increase the customer value proposition to use electronic payments; increase customer convenience; and increase efficiencies due to specialisation in payments. This policy dialogue preceded circulars mandating peer to peer interoperability and work on a national switch for real time micropayments.

Why the rush for interoperability? – especially when some regulators opine that digital financial services is in its infancy and there is a danger in being too prescriptive, whilst the industry is still learning. From a policy maker’s perspective, interoperability facilitates an efficient payment system, as it enables real time micro payments to be made and cleared between any account or any wallet. Subject to the application of Know Your Customer (KYC) requirements it facilitates visibility within financial transactions supporting national and international requirements for Anti Money Laundering (AML) and Combatting the Financing of Terrorism (CFT).

Practically, what difference can it make? In Kenya Safaricom provided widespread peer to peer interoperability with the M-PESA platform, thereby enabling transfers from bank accounts to wallets and in doing so, facilitating the widespread adoption of merchant payments. The Kenya Interbank Transaction Switch (KITS) operated by the Kenya Banker’s Association facilitates real time transfers of up to approximately $10,000, through participating bank accounts. In India through accounts linked to the digital national identity – the Aadhaar and the Unified Payments Interface (UPI) is providing access to financial services for millions through low cost agency operations operated by special purpose payment banks or small finance banks, besides traditional commercial banks. Interoperability combined with digitised information will enable Indians to shop for loans between multiple institutions.

Enabling interoperability is different from having a system which embraces interoperability. This is due to multiple challenges, one of which is pricing. For example, in Uganda it is possible to transfer funds between mobile money providers and to ‘cash out’ across networks. However, few chose to do this directly in part due to high cash-out fees on intra-network transactions.

There is a debate amongst policy makers and regulators on conceptual frameworks for interoperability – whether to use market- or state-based. In Kenya, the regulatory philosophy is for market based interoperability where the market defines the price and there can be multiple providers; hence the provision of services through KITS in addition to most players connecting directly to Safaricom’s M-PESA. In Nigeria, the government stepped in to create the Nigeria Interbank Switch (NIBSS), which it then mandated that institutions should connect to. This was a policy decision influenced by perceived inaction in the marketplace. In India, there are multiple solutions providing interoperability.

Price sensitivity is a factor in some markets. Market leaders often use pricing to stifle competition. Digital finance enables very low-cost transactions, but still in some markets pricing discourages wallet to bank and bank to wallet transactions. This makes it uneconomic, for example, to save small amounts to a bank account through a mobile provider’s wallet.

India shows elements of market and command philosophies; whilst there are several national payment mechanisms, the interchange fees on the switches are kept low to boost interoperability and market acceptance. Policy makers’ desire for a low-cost debit card, which any Indian could use at a fraction of the cost of EMV[1] compliant cards was a factor in the creation by the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI), of the RuPay card.

From the perspective of financial institutions, market based mechanisms are often preferred especially by market leaders, who can use their market position to influence interchange fees. For a market leader, the commercials around interoperability are often key; they can be reluctant to share their network of agents for example with other institutions because: a) the interchange fee may not be sufficient to facilitate liquidity management and b) due to competitive positioning. Thus, for Kenya Commercial Bank, the fee structure of mVisa made it less attractive as a product for the bank.

A regulator, therefore, must contend with, and balance, policy imperatives for cheap and convenient access, with ensuring sufficient incentives for market based mechanisms to encourage the provision of the infrastructure on which interoperability relies. The challenge is to create an environment where different market players can play to their strengths and respond to the unique characteristics of the country they operate in, which can include widely disbursed populations such as in Tanzania or Zambia.

In the words of one regulator “Retail payments are dynamic – the regulator needs to provide space for this dynamism and for different actors to play a role, over time this will reduce costs”.

*Interoperability means a set of arrangements, procedures and standards that allow participants in different payment schemes to conduct and settle payments across systems while continuing to operate also in their own respective systems. Definition by CPSS

[1] EuroCard, MasterCard, Visa (EMV), a defacto standard in the payments industry

Progress and Challenges with KYC and Digital ID

Based on great inputs and discussions from Amrik Heyer, FSD Kenya, Stephen Mwaura, former Head of Payments, Central Bank of Kenya, Uma Shankar Paliwal, Former Executive Director, RBI, Dennis Njau, Head of Channels, Kenya Commercial Bank, Gang Chai, Payment Policy Manager, Central Bank of Nigeria, and Johnah Nzioki from Eclectics.

“Identification provides a foundation for other rights and gives a voice to the voiceless.” – Makhtar Diop, World Bank Vice President for Africa

At a recent workshop organised by The Helix Institute, leading DFS industry players, including providers, regulators, aggregators, and technology providers, came together to deliberate on innovative ways of addressing the key challenges that face agent networks. They split up into three groups to look at the key issues in the context of 1) policy and regulation, 2) strategy and market evolution, and 3) operations.

This blog post details observations from the policy and regulation group, as listed in the following section.

Digital Financial Services has Driven Financial Inclusion

Premised on digital and mobile solutions, Digital Financial Services (DFS) has transformed the landscape of the financial sector. It has brought about increased efficiency, convenience, and consumer options. DFS has increased access to financial services for a population that has hitherto been financially excluded. As per GSMA’s 2016 State of the Industry Report-Decade Edition, there are 500 million registered mobile money accounts globally, of which 118 million are active (on the basis of at least one transaction in 30 days). The number of active mobile money agents (on the same basis) stands at 2.3 million.

Large Numbers Still Lack KYC Compliant Identification

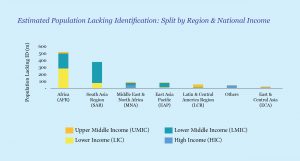

Historically, opening a bank account in many markets has proved to be a challenge due to Know Your Customer (KYC) guidelines, which require proof of identity and address. Unbanked groups often suffer disproportionately as a result of their inability to offer proof of identity. Such identification is generally based on birth certificates and passports, and proof of address based on utility bill payments. Over a billion (17.7 %) of the world’s population [1] remain unable to meet official KYC requirements. The World Bank ID4D 2017 Global data set shows the estimated population that lack identification, as seen in the adjoining graph.

Lack of KYC Compliance Excludes People from Accessing Formal Financial Services

Lack of KYC Compliance Excludes People from Accessing Formal Financial Services

People who fail to meet KYC requirements are excluded from accessing formal financial services, including savings accounts, loans, remittances, insurance, and pensions, among others. However, the problem goes deeper, and often such people are unable to digitally receive benefits from the government, including payments for social security, basic health care, and primary and secondary education. Lack of identification also prevents them from receiving international remittance through formal channels.

Lack of KYC Compliance Impedes Mobile Money and Agent Banking

Volume is the main factor that drives the business-case for institutions that offer digital financial services. This means that providers must increase their customer base and focus on onboarding large numbers of new customers – a process that becomes easier if simple and effective ways to satisfy KYC requirements are introduced.

KYC Acts as a Multipurpose Enabler

Conversely, the existence of KYC-compliant documentation that enables efficient onboarding of customers can have a number of enabling effects. These include a) facilitating mechanisms that may not require a branch, b) allowing harmonisation of government databases for Government-to-Person (G2P) payments, c) enabling transaction mechanisms that do not require signatures, and d) facilitating access to tailor-made financial services suited to a range of customer groups.

Identity Comes in Several Forms

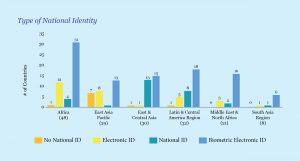

The World Bank ID4D 2016 data set (see adjoining graph) indicates the progress of national identity card systems of various countries and regions as per the World Bank Group’s Identification for Development initiative.

Digital forms of identification are gradually replacing paper-based national identification documents. Electronic ID is a form of identification that can be used for online or offline identification purposes, often in the form of a photo-card with an embedded chip that contains information. A biometric electronic ID adds another layer of identification, usually based on fingerprints. In this context, it is useful to note that a few countries still lack a system of national identity. These are usually countries in conflict.

Digital forms of identification are gradually replacing paper-based national identification documents. Electronic ID is a form of identification that can be used for online or offline identification purposes, often in the form of a photo-card with an embedded chip that contains information. A biometric electronic ID adds another layer of identification, usually based on fingerprints. In this context, it is useful to note that a few countries still lack a system of national identity. These are usually countries in conflict.

The KYC Journey Often Starts with Simplified KYC Requirements

In most markets, subscribing to mobile money is easier than opening a bank account. The required level of KYC varies between mobile money and bank accounts. Higher levels of KYC are usually required for opening bank accounts due to the higher transactional value and volumes, as well as nature of banking products. This is a key reason for the growth of mobile money when compared to agent banking in many markets.

Simplified KYC can Enable Limited Access for Large Populations

Countries without national identification have sometimes introduced simplified KYC guidelines to enhance financial inclusion. This includes restrictions on transaction values (deposits/withdrawals/transfers) to mitigate anti-money laundering (AML) risks. In such cases, if customers wish to upgrade from a simplified KYC account, they need to provide full KYC-compliant documentation to their financial institution.

Pradhan Mantri Jan-Dhan Yojana (PMJDY), India’s national mission for financial inclusion, ensures access to financial services through simplified KYC requirements. In almost three years, 290 million accounts have been opened under the scheme, with 60% of accounts in rural and semi-urban areas. These accounts hold USD 9.9 billion worth of savings, which translates to an average balance of USD 34.

The financial Sector may Create Financial Identity, but It Would Likely be Insufficient

Challenges in the rollout of national identification forced the Nigerian banking sector to provide all banked customers with a Bank Verification Number (BVN). Enrolment of BVN involves capturing a customer’s details, including fingerprint and facial image, after which a BVN is generated. The BVN is expected to minimise the incidence of fraud and money-laundering in the financial system and enhance financial inclusion. Prior to the introduction of national identity, Bank of Uganda mandated the Credit Reference Bureau (CRB) to create a financial identity card and to link to CRB. After signing up an initial 900,000 customers, 150,000 customers were being added annually. As it turned out, the financial identity card in Uganda was not sufficient, nor was it designed to drive financial inclusion [2].

Simplified KYC and/or Financial Sector Identification is Often a Stage in the Path to Full Financial Access

Mobile money with simplified KYC is an effective way to on-board large numbers of customers. However, in more mature DFS markets, there has been a high demand for facilitating mobile phone-based access to full banking services.

Mobile money with simplified KYC is an effective way to on-board large numbers of customers. However, in more mature DFS markets, there has been a high demand for facilitating mobile phone-based access to full banking services.

Equity Bank in Kenya has observed that customers conduct more than double the number of transactions at agents when compared to transactions at the bank branch and ATMs, while self-initiated transactions conducted on customers’ mobile devices amount to four times those made at agents.

Meeting KYC Requirements is a Particular Challenge for Refugee Populations

By the end of 2015, war, conflicts, and natural disasters had forcefully displaced an unprecedented 65 million [3] people around the world. Refugees and displaced populations face great challenges in obtaining formal identity and proof of residence, and often fail to meet KYC requirements. A few countries, including Egypt, Zambia, and Uganda, have allowed refugees to open mobile wallets using government attestation cards or through UN refugee registration cards issued by UNHCR. However, regulators report that providing identification to refugees needs careful application due to Anti Money Laundering and Combating the Financing of Terrorism regulations and acts.

Fragmentation of Records Pose Challenges to Digitising Identity

For many governments, the evolution from paper-based identity to digital identity proves challenging. It requires a huge capital investment to create a national database and to remove duplicate records from multiple existing databases so that there is a single identification number per individual.

Digital Identification can Facilitate Rapid On-boarding and Competition among Providers

Access to national identification databases varies from country to country. Yet, the drive for financial inclusion requires regulated financial institutions to be able to avail digital access for free or for a low fee. Government and private institutions in Kenya have been progressing with an Integrated Population Registration System (IPRS), a central database to verify the identity of a citizen and residents. Commercial banks, telecommunications companies, and other institutions are digitally linked to the National Population Register of the IPRS and have been using this information for efficient customer on-boarding.

Given that on-boarding customers is easier with digital identification, competition can be facilitated by removing barriers, not only to on-boarding but also to the movement of customers. For instance, in India, the IndiaStack API has been designed to use unique digital infrastructure that links a biometric identity (known as Aadhaar) combined with a digital locker that contains customer documents and certificates, to enable banks to provide competing loan offers to potential customers without submitting any physical documents.

Is there a Balance between Customer Protection/Privacy and Data Sharing of Digital Identification?

In the cases where governments have allowed public and private institutions to access the digital ID database, it is important to decide the extent of information that should be shared with various institutions. Such information ranges from complete details about the individual, including full KYC, to top-level verification that safeguards the privacy of citizens. For instance, in India, the government has not limited Aadhaar to being a means of identification to deliver government subsidies and services alone. Private agencies like financial institutions or telecom companies can use Aadhaar for the purpose of electronic KYC, which replaces the physical proof of identity/proof of address documents. Private players may also use Aadhaar to authenticate transactions based on biometrics. In other words, in the federated structure, the demographic data including biometrics reside with the government agency. Other agencies, including private ones, are allowed to fetch the required demographic data for KYC and biometric match-based confirmation to authenticate transactions on a real-time basis.

Conclusion

Digital identity and KYC, including tiered KYC, are vital components to on-board large numbers of unbanked and under-banked people to mobile money accounts and bank accounts in a rapid, cost-effective manner. With large populations possessing a digital account, and with digital identity being accessed by the government and financial and payment sectors, there is a distinct possibility that G2P payments, merchant payments, and technology-enabled financial services will show rapid evolution worldwide.

[1] The World Bank Group’s Identification for Development (ID4D) initiative

[2] Based on a presentation to the Alliance for Financial Inclusion

[3] UNHCR 2016

A Strategic Approach for Next-Generation DFS Agent Networks

With special thanks and acknowledgement to Abhinav Sinha (EKO India), Tamara Cook (FSD Kenya), Kwame Oppong (CGAP), Paul Mbugua (Eclectics), Paul Musoke (FSD Africa), and Abigail Komu (Independent Consultant).

Some people may argue that agent networks will soon go extinct. Even if that is the case, it will not happen until long into the future. In our opinion, agents in the developing world, where about 75% of the unbanked populations live, will remain the core bridges between cash and digital value. Agent network management, however, remains the most operationally burdensome and, at between 40–80% of business revenue, costly element of the digital financial service (DFS) value chain.

On 23rd June 2017, MicroSave wrapped up its four-year expedition, namely the ‘Agent Network Accelerator Programme’ (ANA) with a day-long workshop held in Nairobi. Industry experts and representatives of various stakeholder institutions across the globe came to deliberate on the lessons learnt over the years and discuss the next generation of agent models.

From the surveys conducted by The Helix Institute, including the nationally representative ANA surveys, it is clear that most financial service providers now understand the key challenges to agent network management, as well as their ultimate obligation to move beyond the role of agents as bridges. Providers should be designing strategies that take market evolution into consideration. On the demand side, the needs, preferences, and perceptions of customers are changing. Meanwhile, on the supply side, it is increasingly becoming vital to manage costs while providing services to all market segments efficiently.

The workshop in Nairobi identified two critical elements that form the basis of future-proof agent network deployment strategies. These two elements – interoperability and innovation – ensure sustainable agent models that are able to respond to rapidly changing business environments.

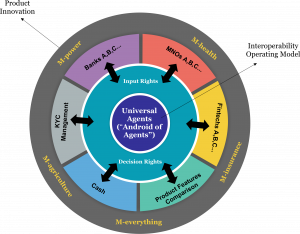

Interoperability

As long ago as 2012, industry experts identified an open and fully interoperable market as the future. A lot of writings have focussed on interoperability and its benefits. Yet here, at the axis of interoperability lies the “android of agents”, or a universal agent. What this means is that industry players should serve customers through a shared agent network. Thus, banks, mobile network operators, and third-party fintech entities would all share a universal agent. This universal agent does not need to hold separate e-values for each client, unlike most non-exclusive agents today. At the core of the universal agent’s services is a comparison of the products and services from the different players, which creates a more transparent market and allows customers to easily access information.

On the supply side of the ecosystem, a unified platform would help customers access financial services from anyone who wishes to offer them. Shared agents and a unified e-currency will allow providers to focus on offering relevant products and not on building expensive agent networks or channels that eat into their bottom line.

On the supply side of the ecosystem, a unified platform would help customers access financial services from anyone who wishes to offer them. Shared agents and a unified e-currency will allow providers to focus on offering relevant products and not on building expensive agent networks or channels that eat into their bottom line.

On the demand side, customers are increasingly changing and are beginning to look beyond the available products. They are keen to avail premium services that go with product delivery. There has been a revolution in financial services, as it has evolved to mobile, wearable devices, and the Internet of Things (IOT). Customer expectations from financial service providers have evolved as well. Now, more than half of consumer bank interactions take place through online or mobile channels.

A recent report by Accenture identified a number of factors that have brought about change in the digital finance landscape. The report notes that consumers are increasingly willing to share more of their personal data in anticipation of benefits from providers. Digital platforms attract younger consumers as an alternative for accessing financial services, while more customers are starting to accept automated support services. In the light of such trends, financial service providers have to engage in constant innovation and develop novel products and services to survive.

The players behind the universal agent described above collectively create the ‘finance store’. Providers, therefore, compete in terms of product and not channel. Customers then assess what is available at the universal agent points, where they choose their own products and use-cases.

Providers have been building expensive distribution networks, and often struggle to keep up as customers’ needs evolve to demand easier and quicker access. It is therefore wise to focus on the product offering and share agent channels to respond to changing demand quickly.

| The workshop experts see the potential of an amalgamation of industries, which enable institutions to work together and provide value-added services to basic financial provisions. For the low-income segments, let us consider the basic human needs of food, shelter, and clothing. How are customers spending to meet these requirements? How can financial service providers partner with entities in these sectors to create value-added products and services, and make their offerings relevant to the populace? On considering other higher income segments, what extras beyond the basic requirements do customers spend on? What other value-added services can be created? The answers to these questions will inform the strategies of financial services for the future business case of the agents.

A good example of this amalgamation is how digital financial services have been transforming agriculture (m-agric). Laying down the necessary digital payment structures in agriculture is important to improve the sector. When this is achieved, subsequent growth of other components of financial services will be realised. One such component is access to credit, which is fundamental to agriculture value chains. Example: Umati Capital (UCAP) in Kenya Umati Capital is a non-bank financial intermediary that focusses on the provision of supply chain finance across various value chains. They leverage technology to provide financing to SMEs who supply to their corporate trading partners. Umati Capital seeks to address two key problems for its identified customer segments: • Access to working capital for small business suppliers of medium and large-sized corporates; • Provision of a supplier financing programme that is tailored to the supplier’s payment cycles. Currently engaged in the dairy sector in Kenya, UCAP uses technology to make faster lending decisions. With funds from angel investors, UCAP has set up mobile applications throughout each stage of the value chain to capture data and inform their disbursal of smallholder farmer loans via mobile wallets. UCAP has currently been running a pilot with 320 dairy farmers. The results are promising and Umati Capital has plans to scale up two major processors to reach 200,000 dairy farmers. |

Innovation

Providers need rapid innovation to respond to the changing demands of consumers. In the future, providers will need to continue prioritising innovation. They must deliver financial services that respond to the market’s needs and mental models for money management, and thus have a real social impact.

Innovation that is driven by the amalgamation of industries has already begun with m-agric, m-health, m‑water, m-power, etc. But it is yet to scale due to the lack of data-sharing and analytics that could potentially make the services relevant to their customers’ everyday lives. This is crucial and should be considered to create more digital use-cases for customers. The ‘universal agent model’ will create a richer data pool, where identifying the 5Vs of data (value, volume, velocity, veracity, and variety) will enhance the continued innovation of products. Product innovation that focusses on meeting customer demands will be essential to sustain the agent network and safeguard agent viability.

How do we ensure provider buy-in?

It is evident that a lot is to be gained through these types of strategies for the future. These gains include, among others, new products, higher quality, less-costly agent networks, improved liquidity management, money that remains digital in the ecosystem, new customers, and new use-cases.

However, there are some impediments to adoption by financial service providers, as outlined in the following section.

1: Sunk Costs: Many providers have made large investments in the form of expenses, time, and effort in legacy systems or distribution models. How can they now put that aside and become open to sharing? Understandably, the providers would be keen to reap the rewards from existing systems and agent networks before entering the coopetition (collaborating while competing) arena. In fact, many providers see their agent networks as a key source of competitive advantage. This will be a question of timing and nature of the market. Yet, as the market ultimately evolves, attempts to hold on to the past will only ensure their obsolescence. As the future unfolds, the platforms and distribution networks of providers are expected to become increasingly irrelevant.

2: Time Horizon: As GSMA has pointed out, both significant investments and serious intent are required to ensure that mobile money systems flourish and yield profits. Indeed, this is the key differentiator between mobile money deployments that ‘sprint’ and those that ‘limp’. But many providers already under-invest in a business that calls for large-scale upfront as well as ongoing investments to achieve scale and succeed. So it is fair to assume that many providers will hesitate to embrace further investment in the future because they anticipate long break-even periods. In this case, it is ideal to see things from a collective perspective – considering multiple entities/providers – where there would be a merger of volumes from the combined customer base, combined transactions numbers, etc. The break-even ball game would change from being linear, where a provider hopes to make profits after a period of time from expected transactions for a single source, to a stage where the provider makes profits from parallel sources due to partnerships. An instance of this is the monies raised from opening APIs, where there is a technological cost to every API call.

3: Risks: Providers are likely to express concerns about unforeseen or expected new risks that would arise through the coopetition model. However, there is a need to embrace risk to design robust mitigation strategies to provide financial services. It calls for collectively identifying and documenting risks as and when they occur, as a measure of planning against future occurrences. Indeed, the coopetition model is likely to facilitate sharing information and integrating systems to better mitigate risk. Fearing risk will simply inhibit innovation as the market evolves.

Conclusion

Is it possible to begin developing tomorrow’s distribution network today? How do we develop deployments that enable and facilitate the demand and supply equilibrium? The solution lies in finding that equilibrium. This can be explored by enabling a single e-currency to serve multiple financial services, developing a real-time self-initiated request platform for customers, encouraging innovation and coopetition, and aiming at social impact for daily relevance. The future starts tomorrow!01

Liquidity—Solving agents’ perennial problem

Based on insightful inputs from Maurice Oyare (PesaPoint), Joseck Mudiri (IFC), Edwin Otieno (Software Group), George Muga (Airtel-Africa), Edwin Odira (Telkom), Paul Langlois-Meurinne (Optimetrics), Nic Wasunna (GSMA) and Wilfred Ndirangu (Eclectics).

The Helix Institute’s Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) surveys show that agents across the globe cite four key challenges to effective liquidity management. Almost all agents express concerns about their inability to predict and respond to fluctuations in the demand for liquidity. Many wonder how long it takes to get to, and how much time they must wait at, their rebalancing point, which is usually a bank. Agents also worry that they must close their businesses when they have to devote time to rebalance. Furthermore, many agents cite their lack of resources to buy sufficient float to keep their agencies liquid.

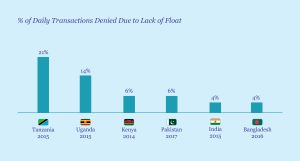

Inefficient cash and e-float management make for unreliable services. As a result, agents find themselves unable to conduct as many as one in five transactions for want of liquidity (see graph below). They are also not able to adopt innovative, if occasionally risky, workarounds.

Inefficient cash and e-float management make for unreliable services. As a result, agents find themselves unable to conduct as many as one in five transactions for want of liquidity (see graph below). They are also not able to adopt innovative, if occasionally risky, workarounds.

Illiquid agents negatively impact customer trust in DFS. This, in turn, reduces both uptake and usage of the service – thereby decreasing the return on investment for agents and providers alike. In many cases, the response of agents and providers is to further reduce their investment in the service, thus creating a negative downward spiral. Small wonder that for each among GSMA MMU’s 35 “sprinters” (with more than a million active customers), there are eight deployments that limp along, operating in the sub-scale trap.

Leading players in the DFS industry, including providers, regulators, aggregators, and technology providers, came together in a recent workshop organised by MicroSave’s Helix Institute. They deliberated on innovative ways to address the challenges facing agent networks. The participants divided themselves into three groups to look at key issues in the context of policy and regulation, strategy and market evolution, and operations.

Leading players in the DFS industry, including providers, regulators, aggregators, and technology providers, came together in a recent workshop organised by MicroSave’s Helix Institute. They deliberated on innovative ways to address the challenges facing agent networks. The participants divided themselves into three groups to look at key issues in the context of policy and regulation, strategy and market evolution, and operations.

The operations group unanimously identified liquidity management as the primary challenge to agent networks. They began by defining the problems to then devise solutions. The following issues were identified as a result of the exercise.

1. ‘Hands-off’’ Approach to Liquidity Management by Providers

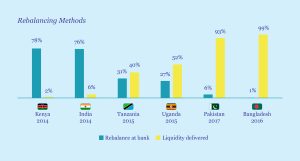

Outside Bangladesh and Pakistan, (where liquidity is usually delivered by ‘runners’ who visit agent outlets to provide e-float or cash), most providers operate on the assumption that liquidity management is the responsibility of the agent.

In the case of better deployments, efforts are being made to establish ‘Super Agents’, such as banks, microfinance institutions, cooperatives and even supermarkets, etc. These Super Agents provide re-balancing points where agents can exchange excess e-float for cash and vice-versa. Many deployments also use a ‘Master Agent’ system to recruit, manage and monitor agents. This often plays an important role in liquidity management, particularly in urban/peri-urban areas in countries like Uganda and Tanzania.

In the case of better deployments, efforts are being made to establish ‘Super Agents’, such as banks, microfinance institutions, cooperatives and even supermarkets, etc. These Super Agents provide re-balancing points where agents can exchange excess e-float for cash and vice-versa. Many deployments also use a ‘Master Agent’ system to recruit, manage and monitor agents. This often plays an important role in liquidity management, particularly in urban/peri-urban areas in countries like Uganda and Tanzania.

Agents located in rural areas face a specific set of problems. Their far-flung locations imply long distances from providers or Master Agents. They are thus less likely to receive effective or regular support. Moreover, many of the transactions in these areas require ‘cash-out’ of P2P remittances sent from urban areas – so rural agents end up accumulating e-float.

More sophisticated platforms allow providers to track how much e-float an agent holds at a given time. In some cases, the platforms may also provide a portal for Master Agents. These methods allow providers to alert agents and their supervisors when they need to rebalance e-float. However, these systems are unable to track cash balances, which change as the agent sells (and sometimes buys) goods in addition to performing DFS cash-ins and cash-outs.

2. Absence of a Digital Ecosystem

Even in the most developed DFS ecosystems, cash remains king. While providers seek to grow ecosystems through merchants and businesses that accept mobile money payments, interoperability between providers remains rare. The lack of fully interoperable platforms implies that non-exclusive agents who service multiple providers have to maintain separate e-float pools for each. These e-float silos compel agents to spread their working capital for agency across multiple providers, which often reduces the amounts held for each.

What Can Providers Do in This Situation?

Most of the key problem areas are manageable. Some ways in which the providers may address the issues related to improving agents to liquidity are outlined in the following section.

1. Innovative Agent Platforms

Providers need to reconsider existing approaches to agent monitoring and management. Centralised monitoring systems can help identify agents who consistently fail to hold adequate liquidity. Alerts can then be sent to agents whose float levels have dipped below a recommended level to encourage rebalancing.

Novopay in India has a Network Operations Centre (NOC) ‘war room’ with an enormous screen that lets its staff see agent behaviour and transactions at different levels, from country-wide, through individual states, all the way down to individual agents. At the agent-level, Novopay can identify the device being used, track liquidity and even watch the progress of agents through each transaction screen. They can identify if and where the agents make mistakes. Remote-monitoring of tariff display and branding are done by asking agents to submit date-stamped photos of their outlets. Training, alerts and tips are delivered through the agents’ mobile devices. As a result, Novopay has a limited number of in-the-field monitors. Almost all the monitoring is done from their head office in Bangalore over the phone.

These platforms could also facilitate a variety of rebalancing mechanisms. These include rebalancing at ATMs, as well as through inter-agent transfers, where agents can ask for and receive e-float from fellow agents. Agents may also choose to deposit/withdraw money from their personal account into the float account remotely without involving the bank. This is already being done informally on WhatsApp groups set up by Master Agents to manage their agent networks. If providers are able to monitor these activities, they could monitor compliance and define standard operating procedures for their agents.

2. Uber-isation of Agents

Building on the ideas around inter-agent transfers, the group discussed the potential to reduce the dependence on agents by empowering almost every customer to act as cash-in/cash-out (CICO) points. This, of course, is already being done on an informal basis across the globe – particularly in remote areas that are poorly served by agents who are formally supported by providers. Often, local business people or community leaders provide services to convert cash into e-value or vice-versa in an informal manner for a small commission. Using such an approach would mean an increased network of CICO points as well as reduced agency management costs for providers. Customers would benefit from the convenience of proximate services.

In “Reimagining The Last Mile – Agent Networks in India” MicroSave highlighted that “fintech companies can come up with smartphone applications that enable any user to act as liquidity merchants ― mimicking what Uber has done for transportation. Similar initiatives can help address cash needs in the ‘last few hundred yards,’ while agents provide the ‘last-mile’ backup underpinning a more decentralised cash market. To make it work effectively, it needs to be ubiquitous and interoperable across providers.”

“Such a smartphone app should implement a geo-referenced marketplace for cash, to supplement an agent network. Users who have need for cash-in or cash-out should be able to search for other willing users in their vicinity. The application should do the match-making on the basis of availability and willingness to connect two ends of the network. The transactions need not be intermediated by the service provider (though the transactions between the two parties should be on the service provider’s system). The app should offer a search capability, as well as a variety of trust-building mechanisms.” – MicroSave.

Along these lines, Eko Financial Services Pvt. Ltd has launched an app called Fundu, which is being geared up for a pilot-test in Kenya. “This app will allow you to act as an ATM… Whenever a Fundu app user near you needs cash, you will get a notification. If you have cash and are willing to provide it, you can accept the request.” The individual will transfer the money to the user’s bank account using his or her virtual address. – LiveMint.

The elegance of this solution is that the users do not need to meet or even know one another. The shortcoming is that there is no scope for the exchange of physical cash. Our discussions with industry stakeholders highlight concerns for the security of agents who currently operate on such ‘Uber-ised’ solutions. Their concerns are that if agents highlight that they have cash at their outlet, it is an invitation for robbery and/or fraud, both of which are growing at an alarming rate.

3. Use of Data Analytics to Predict Demand

Data analytics could be used to monitor transactions and facilitate liquidity management on the basis of historical experiences and trends. This idea is built on a recommendation made by The Helix Institute in 2014 and Harvard Business School in 2017. Using the DFS platform data to identify trends in agents’ demand for e-float or cash will assist in planning for peaks and troughs. This information could be automatically shared with agents and Master Agents by the platform to assist them to maintain adequate levels of liquidity. The analyses would need some modifications to account for unusual ‘outlier’ events that create spikes in demand for liquidity, such as general elections, large sporting events and intermittent bulk payments like remittances to refugees or government subsidy transfers.

Nonetheless, regular SMSs to agents that predict the likely demand for liquidity on a monthly, weekly and daily basis would help them to plan better. It would also inform provider and Master Agent support such as facilitating e-float overdrafts for agents (see below) or organising cash pick-up or drop-off at agent outlets. Providers can also use this data to monitor agent activity, which will help identify unusual or fraudulent practices, such as remote deposit, split transactions and float hoarding.

4. Credit to Allow Agents to Access Working Capital

Agents often cite lack of resources or working capital as key impediments to financing their liquidity requirements. These impediments are sometimes (but not always) temporary, as a result of seasonal fluctuations. While few mobile network operators are willing to take the risk of lending to their agents, extending e-float on credit provides a significant opportunity to improve liquidity and enhance agent loyalty. If lenders use methods like data analytics, they would be able to predict liquidity needs and assess past performance of agents. This should allow lenders to significantly reduce the risk inherent in offering credit to agents.

Furthermore, a system that provides agents with e-float overdrafts to allow them to rebalance using their mobile phones could unlock significant value. It would also reduce the number of transactions declined for want of liquidity. Safaricom, for instance, offers their premium M-PESA agents short-term weekend/public holiday financing to meet their liquidity requirements. This not only boosts the availability of float but also increases the number of agents working over the weekend when banks and other Super Agents are closed. A few banks, such as Commercial Bank of Africa and Kenya Commercial Bank, are already making steps towards this. However, given the sophisticated data analytics and credit platforms required in the process, fintech companies may be best-suited to provide these lines of credit.

5. Set-up Digital Ecosystems

Digital ecosystems consisting of open APIs and fully interoperable platforms would facilitate and encourage the use of digital payments. This can reduce demands to cash out and need for agents to rebalance. Similarly, when FMCG suppliers insist on payment for supplies in e-value rather than cash, it can help rural agents use the e-float they accumulate. High-functioning digital ecosystems can only be achieved if all the players collaborate to increase opportunities for additional digital transactions.

Effective liquidity management is key to any trusted and successful agent network. Yet the much-vaunted challenges are all manageable, particularly if providers leverage data analytics and the capabilities of fintechs.

Study on adoption of cashlite among MFIs in India

MicroSave, with support from MFIN, conducted this study to capture the experience of cash-lite/cashless models adopted by MFIs in India. The report identifies ways to accelerate the adoption of cash-lite models.