Super Cyclonic Storm Amphan ripped through Bangladesh and the eastern Indian states of West Bengal and Orissa in May, 2020. It left behind more than a hundred dead and millions of lives disrupted. The financial damage is certain to be severe with West Bengal alone predicting losses amounting to USD 13.2 billion. Most of the damage was uninsured and had no disaster risk transfer mechanism in place.

Responding to such disasters is a herculean effort. The top priority is always to save lives. MSC’s work on disaster risk financing projects has enabled our partners to understand the topic better and design need based solutions addressing the disaster recovery needs of the low- and moderate-income (LMI) segments, and MSMEs. Through a two-part blog, we summarize our experiences in the field of disaster risk financing and its application at regional, national, and consumer levels. In the first part of this blog, we provide an introductory, macro overview of layered disaster risk financing, while in the second part, we focus on disaster risk financing approaches from an inclusive finance perspective.

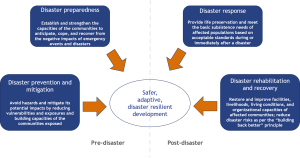

When Amphan struck, India and Bangladesh evacuated millions to safety well ahead.[1] Preparing for disasters and managing their impact has been standardized by most nations by now. The standard framework adopted to manage disaster response is summarized below:

Source: MSC analysis

The need for finance in disaster risk management

Disasters cause monetary losses by damaging physical infrastructure, assets, and lives. The absence of a risk transfer mechanism, therefore, makes rehabilitation even more expensive. Lending to rebuild is further complicated by the different types of disasters and their varied impact. Since the effects of climate change disproportionately affect poor communities around the world, disaster risk financing as a risk transfer mechanism therefore assumes critical relevance. Several stakeholders including policymakers, insurers, financial services providers, and entities are working to develop the resilience of LMI segments against climate change and disasters need,. They, therefore, need a well-grounded understanding of climate change and disaster risk financing mechanisms.

A layered approach to disaster risk financing

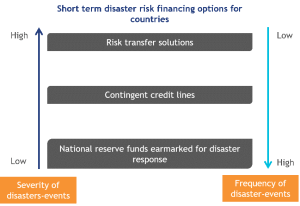

At the national level, a country can assess its risk financing options through a risk layering approach. The idea behind a risk layering approach is to identify the best-suited risk financing tools that are proportional to the severity of the risk and the fiscal capacity of the government. Simply put, disaster risk financing must be cost-effective, yet not compromise a country’s financing requirements at the time of a disaster. Layered disaster risk financing options are illustrated below:

Source: MSC analysis

In the following section, we briefly assess what each of these three layers of financing options entails.

The first layer is the national reserve funds, which generally refer to annual budgetary allocations, contingent budgets, and allocations made by a government in response to disasters. These funds are typically used to cope with localized, low-severity, but high-frequency events like floods, landslides, and earthquakes, etc. The economic capacity of a country would generally determine the amount of such funding. However, due to the implications of huge expenses, most developing countries find it difficult to fund large-scale anomalous disasters.

The second layer comprises contingent credit lines. These pre-arranged credit lines disburse loans to act as precautionary lines of defense in the event of disasters of medium to high severity and meet government expenditures over and above the disaster reserves.

An example of a contingent credit line is the Catastrophe Deferred Drawdown Options or CAT DDOs offered by the World Bank. This innovative contingent line of credit provides immediate liquidity to countries in the event of natural disaster. Funds become available for disbursement after the drawdown trigger—typically the member country’s declaration of a state of emergency. The full commitment amount is available for disbursement at any time within three years from the signing of the financing agreement.

The third layer is risk transfer solutions. The objective is to transfer the financial risks that arise from high-severity, low-frequency disasters from countries or individuals, or both, to a third party in place of a risk premium. Such solutions provide a contractual right to countries or individuals to receive pre-defined funds at the time of a disaster. These solutions can take the form of sovereign insurance or regional risk pools, CAT bonds, and consumer insurance solutions.

We discuss each of the risk transfer mechanisms in more detail below.

- Sovereign risk pools

Through sovereign catastrophe risk pools, countries may pool risk in a diversified portfolio, retain some of the risks, and transfer excess risk to the reinsurance and capital markets. Since the likelihood of a major disaster afflicting several countries within the same year is low, diversification or “geographically spreading the risk” among participating countries creates a more stable and less capital-intensive portfolio. Sovereign risk pools are therefore, less expensive to reinsure. Examples of such risk pools are the Pacific Catastrophe Risk Assessment and Financing Initiative (PCRAFI) and South East Asia Disaster Risk Insurance Facility (SEADRIF).

- CAT Bonds

A catastrophe (CAT) bond is a debt instrument that serves the dual purpose of raising debt and transferring financial risk in the books of the insurance companies. Countries that face disaster risks issues these bonds. Insurance companies and re-insurers are typically the sponsors who pitch the bonds to the potential investors. These instruments promise a higher yield to investors compared to traditional fixed income instruments. In normal circumstances, investors receive coupon payments along with PAR value at the end of maturity. In the event of a disaster, the sponsors suffer financial loss due to claims linked to prior indemnity, indexes, and parameters. In such a circumstance, the sponsors have the right to default on further payments to investors.

The Philippines is a primary example of a country that has used CAT bonds at the national as well as the city level.

An emergent approach used by actors, such as the World Bank has been to combine a CAT bond with a Pandemic Emergency Fund (PEF). A PEF is a mechanism that provides additional financing as non-reimbursable grants in response to outbreaks with pandemic potential. The World Bank pioneered this approach in the Maldives.

- Consumer-level risk transfer solutions

Consumer-level risk transfer solutions are insurance products or programs that provide coverage against disasters and natural calamities. Such solutions can be classified into agricultural and non-agricultural insurance solutions.

Agriculture insurance

Agriculture insurance solutions take one of two forms: state-supported or subsidized agriculture insurance and commercial agriculture insurance.

Agriculture insurance programs are an instrument of choice for farmers and rural communities to cope with the risk of disaster. The provision, administration, and oversight of agricultural insurance programs help a country manage the systemic risks of disasters, such as widespread drought or floods that affect a large number of farmers simultaneously. The cost of managing systemic risks that arise from catastrophic events and affect the agriculture sector is many times higher than the cost of premiums it would take to insure them. For example, the World Bank estimates that a widespread drought in India could generate crop-yield losses as high as three times the average annual crop loss experienced in a normal year. Traditionally, governments in India have mitigated crop failures or other natural disasters by providing post-disaster direct compensation as a relief measure, or through farmer loan waiver schemes—which while popular cannot be regarded as a sustainable mechanism to meet disaster-induced crop losses. The last major waiver in India in 2008 saw the government write off outstanding loans worth USD 7.8 billion for more than 30 million small and marginal farmers.

Insurance, on the other hand, not only reduces the cost of relief but allows governments to make fiscal plans for natural disasters and crop failures. It does so by well-defined premium subsidies for agriculture insurance taken by farmers, thereby allowing the government to gauge its proposed outlay and budget for it. In the event of a disaster, the insurance companies compensate the farmers from their own risk pools without government subsidies. Hence, insurance limits the government’s exposure when a disaster strikes while ensuring optimal risk coverage and compensating the losses of farmers. The biggest state-supported agriculture insurance program among emerging economies is the Pradhan Mantri Fasal Bima Yojana of India.

Non-agriculture disaster risk insurance

Non-agricultural disaster risk insurance solutions protect against damage to property and materials of value in the case of disasters such as floods, earthquakes, typhoons, and cyclones. While property insurance against risks like fire and theft is not new, coverage against disasters is nascent. Many micro and inclusive insurance companies have been experimenting with cash benefit products for low- and middle-income segments. These are typically pre-defined insurance products, where payout are triggered when the insured disaster occurs, irrespective of the damage incurred. We examine this in greater detail in part 2 of this blog.

Getting the disaster risk financing product mix right

Disaster risk financing tools and approaches to mitigate future losses should be a function of the types of disasters to which a country is most vulnerable, as well as potential future humanitarian and financial losses that could arise if such disasters occur. While incorporating the product design features of insurance, countries must also consider the requisite resources to rebuild the infrastructure that has been destroyed using better quality, disaster-resistant material.

Governments must strive for a portfolio mix of disaster risk financing instruments based on accurate risk assessments, desired coverage, available budgets, and cost efficiency. See the second part of this blog here.