Through this video, MicroSave emphasis the use of behavioural research methods and user-centric design in developing financial services that work for all.

Blog

Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) in Fertiliser – Towards an Efficient Fertiliser Distribution System

Forty-eight-year-old Devashekhar cultivates paddy twice a year. A resident of Guntur district in Andhra Pradesh, India, Devashekar purchases between 300 and 350 kg of fertiliser from retailers in his village. He is among many farmers who have now started to pay market price for fertiliser. “There has been a reduction in overcharging by retailers as we now pay market price. We also get a transaction receipt that indicates the selling price of fertiliser,” he says. Devashekhar remembers paying more than the maximum retail price (MRP) written on the bags of fertiliser before the introduction of the direct benefit transfer (DBT) system in fertiliser1. The journey, however, has not been easy, he recalls.

Forty-eight-year-old Devashekhar cultivates paddy twice a year. A resident of Guntur district in Andhra Pradesh, India, Devashekar purchases between 300 and 350 kg of fertiliser from retailers in his village. He is among many farmers who have now started to pay market price for fertiliser. “There has been a reduction in overcharging by retailers as we now pay market price. We also get a transaction receipt that indicates the selling price of fertiliser,” he says. Devashekhar remembers paying more than the maximum retail price (MRP) written on the bags of fertiliser before the introduction of the direct benefit transfer (DBT) system in fertiliser1. The journey, however, has not been easy, he recalls. “During the last Kharif2 season, when I went to buy fertiliser, the retailer refused to sell, citing Aadhaar-based biometric authentication as a mandatory requirement for purchase. I had to go home and return the next day with my Aadhaar number (card). Yet I was unable to purchase fertiliser the following day as well because of a long queue of farmers, whose biometric authentication was taking time due to multiple attempts for authentication. I was finally able to purchase fertiliser on the third day, that too after multiple biometric authentication attempts and waiting in queue for half the day”.

“During the last Kharif2 season, when I went to buy fertiliser, the retailer refused to sell, citing Aadhaar-based biometric authentication as a mandatory requirement for purchase. I had to go home and return the next day with my Aadhaar number (card). Yet I was unable to purchase fertiliser the following day as well because of a long queue of farmers, whose biometric authentication was taking time due to multiple attempts for authentication. I was finally able to purchase fertiliser on the third day, that too after multiple biometric authentication attempts and waiting in queue for half the day”.

Prior to the introduction of DBT, Devashekhar could ask his friends or family members to purchase fertiliser on his behalf but the new system doesn’t provide for this. This adds to his inconvenience but now he understands the purpose behind this step. “The government now records details of every buyer, so diversion and overcharging will certainly reduce,” he adds. It took Devashekhar about eight months to understand and get used to the new system as there was no communication about the programme. Although issues, such as biometric mismatch, authentication failure, and internet connectivity have reduced over time, farmers like Devashekhar end up spending relatively more time than before while buying fertiliser. They also worry about the performance of the system and the on-time availability of fertiliser, especially during the peak Kharif season.

With time, retailers have also become better at operating the new system. Some have even adopted new practices to reduce the time taken to complete transactions. Some retailers end up saving the Aadhaar number in the respective farmers’ mobile phones and also note it in their registers so that the farmers can come to purchase fertiliser directly from the fields without their Aadhaar card and simply authenticate with their biometrics. Some retailers also keep a record of the ‘best finger’ for authentication purposes to improve their chances of successful authentication in the first attempt. This improves the efficiency of the process but raises questions about privacy and security.

MicroSave has been involved in the DBT for fertiliser programme from the beginning and has seen it evolve from two districts in Andhra Pradesh to 14 districts across India. Assessment3 of the programme in February 2017, when only six districts were live,4 helped us to identify key areas for improvement, crucial for the success and national rollout of this programme. These key areas are outlined as follows:

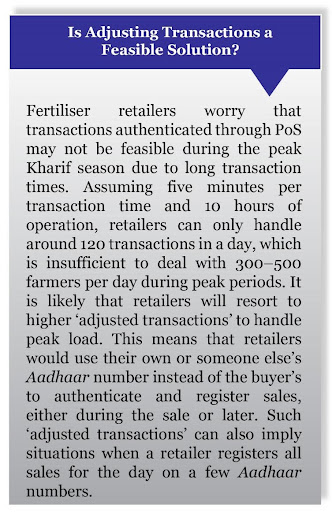

Need for Effective Communication: A strong communication campaign in vernacular, using a mix of Above The Line (ATL) and Below The Line (BTL) communication methods has to be designed to make farmers aware of the objectives and changes. Assessment of the six pilot districts revealed that a majority of the farmers received the information about Aadhaar authentication requirements for purchasing fertiliser only after arriving at the retailer outlet. This leads either to the retailer refusing to sell them fertiliser or to transactions being ‘adjusted’ by the retailers (see box). Moreover, poor communication to farmers allows retailers to continue to overcharge with impunity and leads to the mistaken belief among farmers that the government will somehow transfer the subsidy amount indicated in the (English language) receipt directly into the farmers’ bank accounts rather than to the manufacturer for the fertiliser purchased.

‘Plan B’ for Fertiliser Sales During Peak Season: An ‘early check out’ system to pre-authenticate farmers at designated Points of Authentication (PoA) before they purchase fertiliser can tackle the peak-time transaction load. This would reduce transaction time at the retailer shops. Existing village infrastructures such as Common Service Centres (CSC), Post Offices, Bank Mitrs (BMs), Fair Price Shops (FPS) etc. can be designated as PoAs, where farmers can pre-authenticate the transaction using Aadhaar and book the fertiliser, thus reducing the transaction time on the final purchase day.

Grievance Redress Mechanism (GRM): A formal GRM is important when the DBT in fertiliser is rolled out across India. The GRM should also include the following features:

-

- A toll-free number, which should be well-advertised and communicated to users.

- The complainant should receive a complaint ID once the grievance is registered.

- The complainant should be able to track the resolution status through the complaint ID.

- The government should decide the Turnaround Time (TAT) for grievance resolution.

- The mechanism should also provide for an escalation/responsibility matrix, which automatically escalates the grievance to the next level in the matrix if it is not resolved within the pre-defined TAT at a particular level.

The need to devise and test solutions for these challenges in the subsidy distribution system before it is scaled-up is essential, as about INR 70,000 crore (USD 11 billion) is budgeted for fertiliser subsidy in the financial year 2017-18. Only time will tell if the government will continue transferring fertiliser subsidies directly to producers or these are interim steps towards complete DBT i.e. direct subsidy transfer to farmer’s bank account.

1DBT in fertiliser is a modified subsidy payment system, where fertiliser companies are paid subsidy only after retailers sell the fertiliser to farmers/buyers through successful Aadhaar authentication via Point of Sale (PoS) machines.

2Kharif crops are cultivated and harvested during the rainy season, which lasts from April to October, depending on the area.

3At the time of research, DBT live districts were those six districts where the government paid subsidy payment to fertiliser companies on actual sales realised through PoS machines. The other 10 districts were dry-run districts, where subsidy payment to fertiliser companies was yet not linked to actual sales via PoS.

4On request from National Institute for Transforming India (NITI) Aayog, MicroSave conducted a dipstick evaluation in six districts in Andhra Pradesh (Rangareddy, Pali, Una, Hoshangabad, Krishna, and West Godavari), where DBT pilot was running live.

Agent Network Accelerator Research – Pakistan Country Report 2017

The Agent Network Accelerator (ANA) project is a four-year research project in the following eleven focus countries, managed and conducted by MicroSave/the HelixInstitute of Digital Finance. It is the largest research initiative in the world on mobile money agent networks, designed to determine their success and scale. Pakistan is among 11 African and Asian countries participating in this research project, selected for its contribution to the development of digital financial services globally.

The second wave of the survey for Pakistan, funded by Karandaaz Pakistan, investigates how Pakistan’s mobile money market has evolved since the previous wave of the study in 2014. The survey report is based on over 2,000 mobile money agent interviews that were conducted across Pakistan. The research focuses on operational determinants of success in agent network management, specifically the agent network structure, agent viability, quality of provider support, compliance and risk as well as other important strategic considerations. The study also looked at Pakistan Specific Topics such as BVS Regulations and Gender. The survey is designed to provide valuable insights for the digital financial sector in Pakistan and provide recommendations for developing sustainable networks of mobile money agents. This report highlights the key findings on the mobile money agent landscape in Pakistan.

Have the Portfolio Diversification Strategies of Kenyan Microfinance Banks Failed?

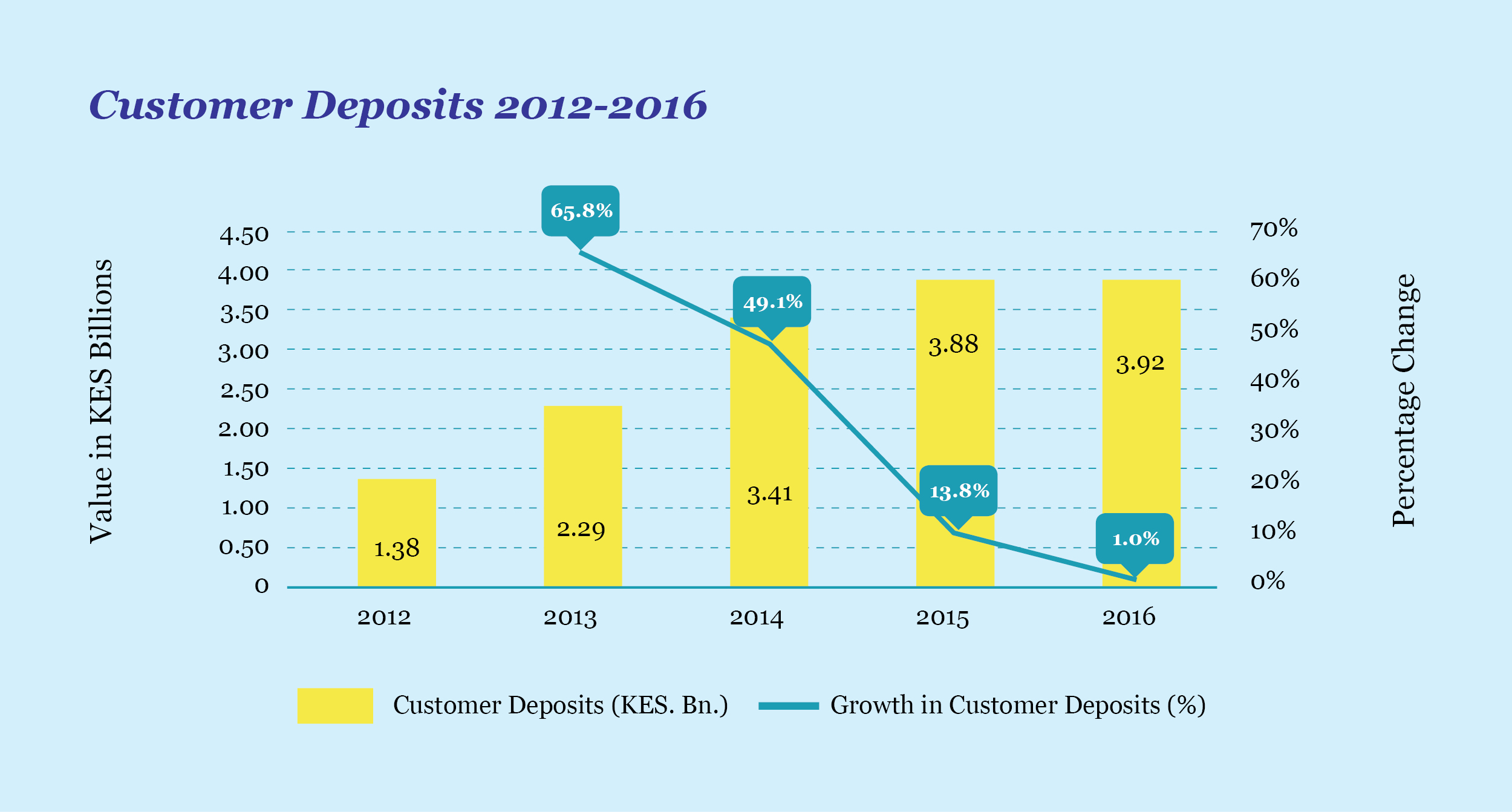

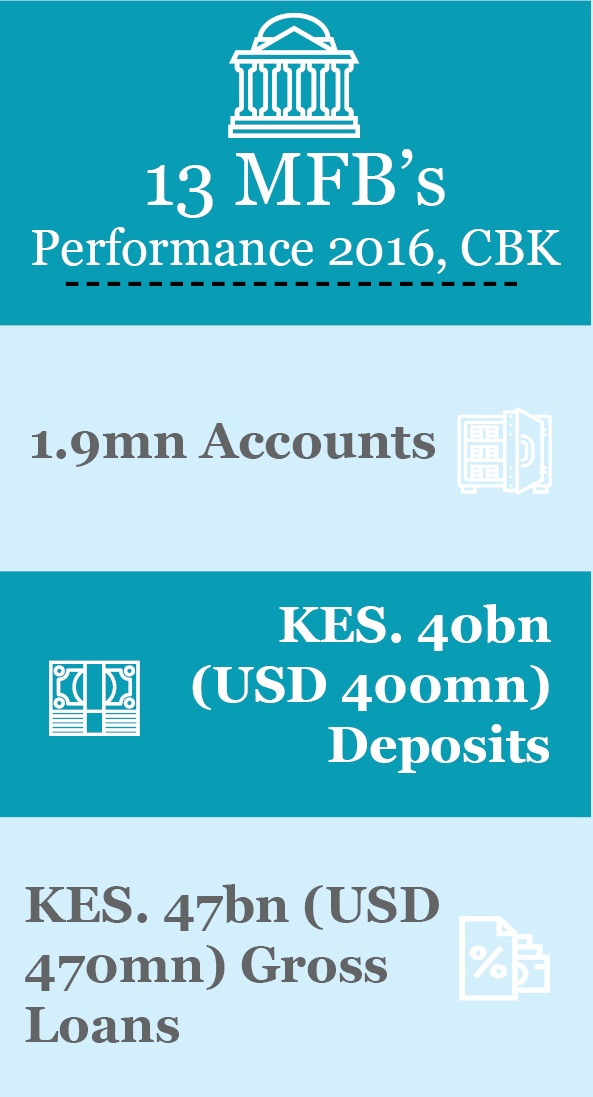

Since the enactment of the Microfinance Act 2006 in May 2008, there have been marked changes observed in the microfinnce industry in Kenya. Over this period, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) has progressively licensed 13 microfinance institutions to operate as microfinance banks (MFBs). Consequently, the industry has continued to experience positive growth. Since 2012, deposit accounts have grown by 12%, deposits by 184%, and loans by 131%. To achieve this, MFBs employed diversification strategies, targeting new markets by developing new products and services for these new clients segments.

industry in Kenya. Over this period, the Central Bank of Kenya (CBK) has progressively licensed 13 microfinance institutions to operate as microfinance banks (MFBs). Consequently, the industry has continued to experience positive growth. Since 2012, deposit accounts have grown by 12%, deposits by 184%, and loans by 131%. To achieve this, MFBs employed diversification strategies, targeting new markets by developing new products and services for these new clients segments.

In addition to the microenterprise segment, MFBs in Kenya now target the Small and Medium Enterprises (SME) segment with targeted products, such as cash flow and asset loans, savings and current accounts, and fixed deposits accounts. Despite these initiatives, almost all performance indicators in the industry, such as profitability, non-performing loans (NPLs), and portfolio-at-risk (PAR) deteriorated in 2016. To understand this trend, MicroSave analysed[1] the financial performance of five leading MFBs[2] in Kenya over a span of five years. The five MFBs share 95% 0f the market between them[3].

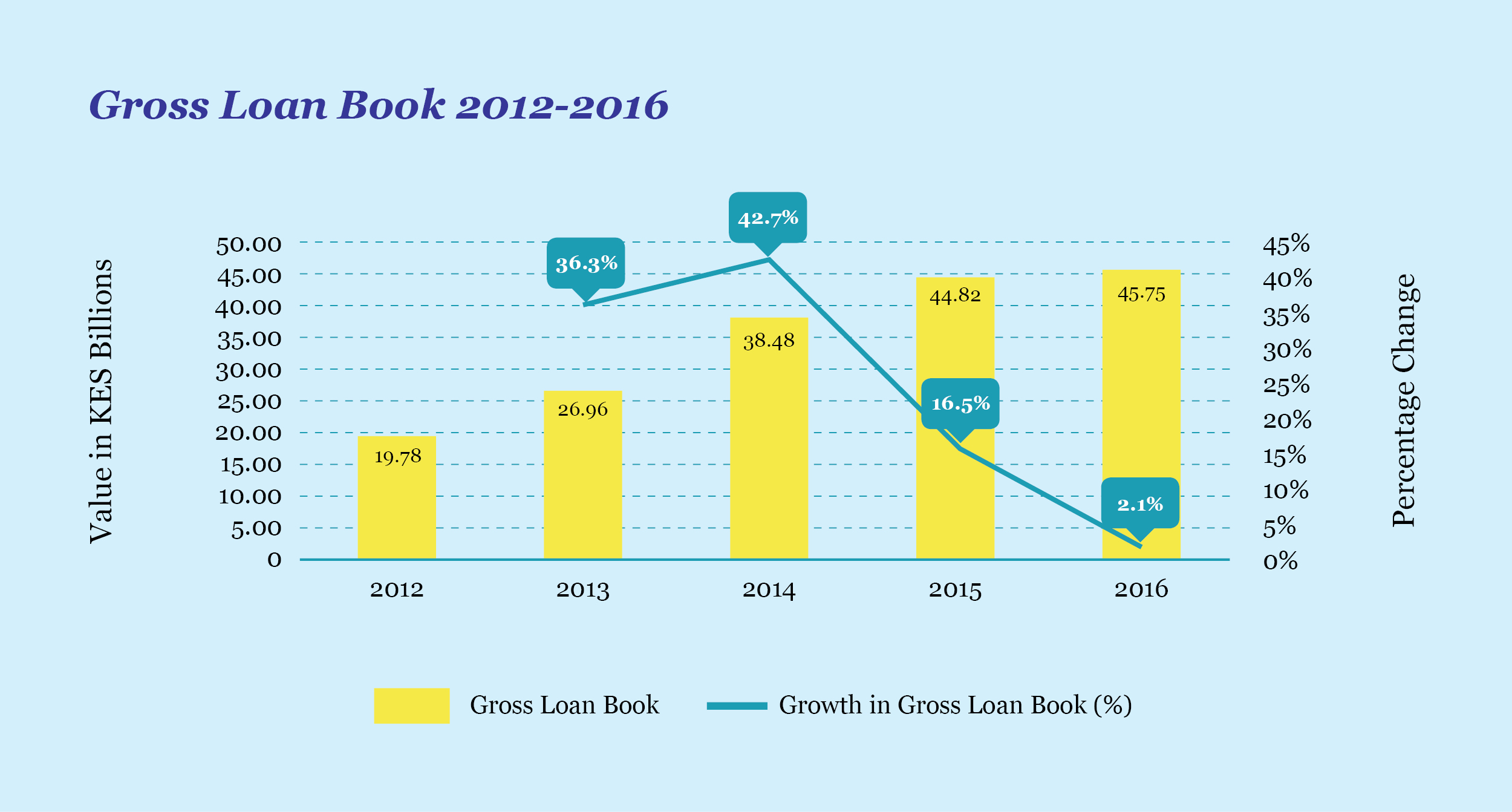

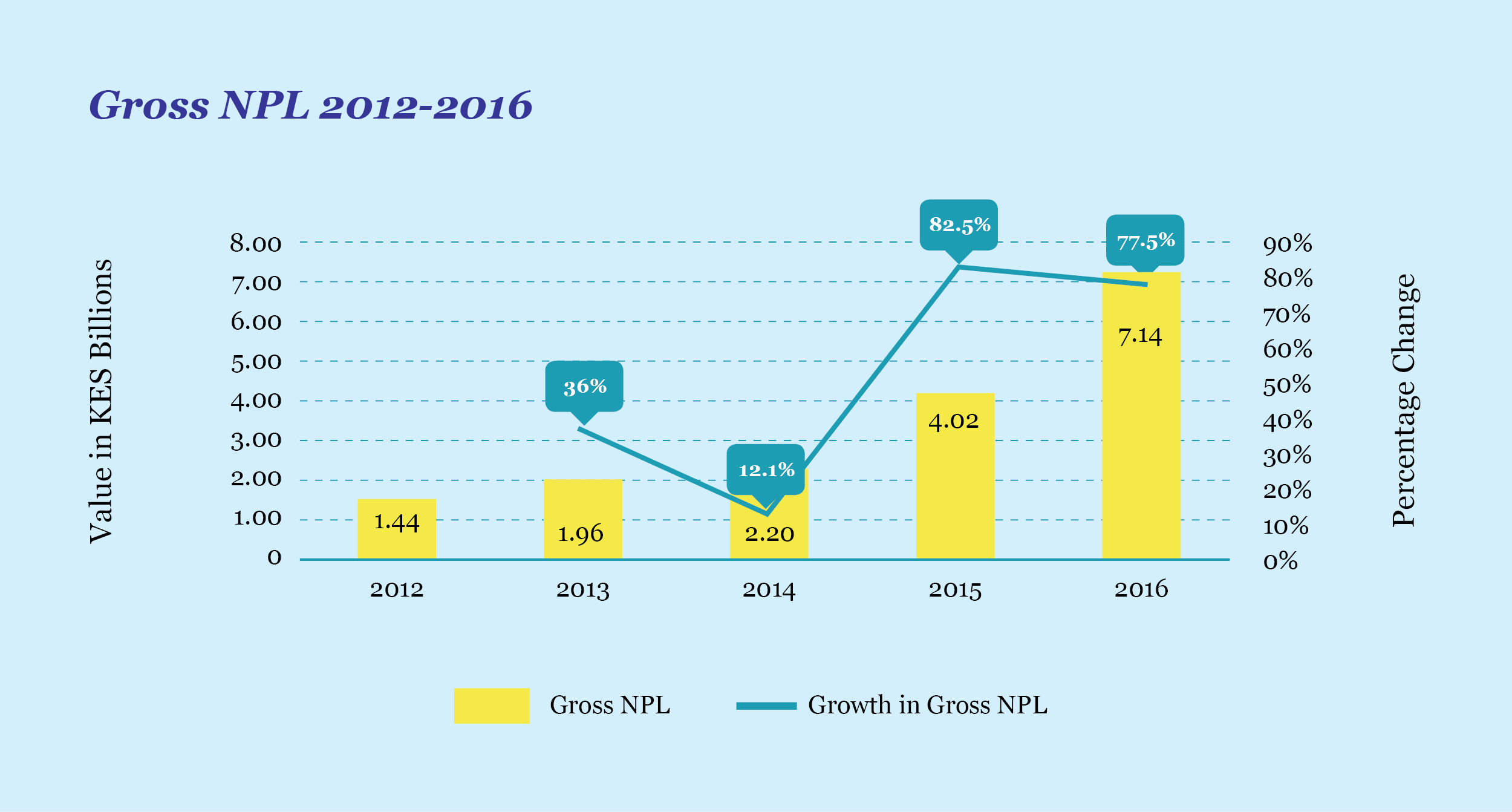

In the past five years, the gross loan book of these five MFBs has grown by 131% to KES 45.7 billion (USD 457 million). In line with this growth, NPLs have also increased by 394% to KES 7.2 billion (USD 72 million) and average PAR steadily increasing from 7% in 2012 to 16% in 2016.

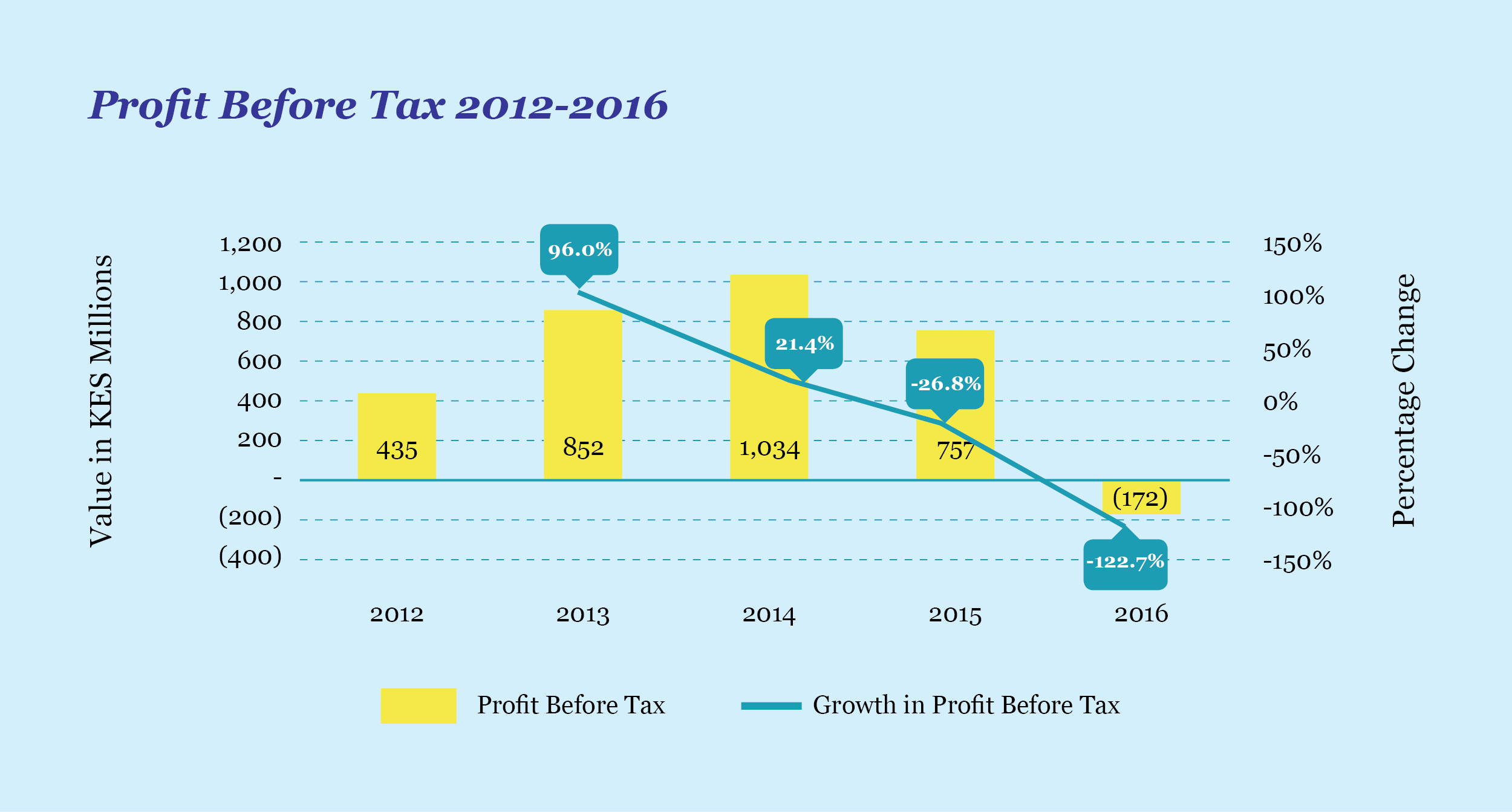

The industry has maintained a declining growth in gross loans and deposits and deteriorating PAR in the years under review. In 2015, the industry realised negative growth, which led to losses in 2016.

With most MFBs holding relatively young SME portfolios, coupled with the fact that they are still stress-testing new systems and structures for this target market, this was perhaps expected. However, the trend still needs to be addressed. With the micro-enterprise portfolio traditionally considered to be less risky, more focus should be placed on stabilising the newer SME portfolio, which carries greater risk. In addition, the International Financial Reporting Standard (IFRS) 9[4],which comes into effect in 2018, requires the reclassification of loans by making higher provisions to absorb shocks. This may consequently contribute to greater losses in the industry. What, therefore, are the underlying factors that increase these risks among MFBs in Kenya?

Firstly, regulatory factors have affected the MFB sector in the past couple of years. The Central Bank of Kenya, in its mandate, to ensure that financial institutions comply with financial regulations, placed three banks (Imperial Bank, Dubai Bank, and Chase Bank) under receivership between 2015 and 2016. As a result, Rafiki MFB, a subsidiary of Chase Bank, suffered immense reputational damage. Low depositor confidence in Rafiki led to an overall shrinkage in the deposit base by 29% in 2016. Similarly, Rafiki’s loan portfolio also shrunk by 17%. At the end of the fiscal year 2016, the MFB reported a gross loss of approximately KES 461 million (USD 4.6 million) before tax. This has significantly contributed to the industry’s pre-tax loss of KES 337 million (USD 3.4 million) in 2016.The Rafiki factor also lowered customer confidence in the MFB sector, which led to lower growth in deposits, at least for 2016.

5-Year Performance Analysis Of Five Leading MFBs in Kenya

Secondly, the SME business model that MFBs adopted has stretched their institutional capacities and skills. Their collective portfolio diversification strategies in new markets and customer segment (SME) might have proved riskier than estimated. Some of the performance challenges that MFBs face could be attributed to the factors highlighted below.

a. Investor influence: Many MFBs have resorted to equity and debt financing to adequately grow the lucrative SME portfolio. This came with pressure to generate profits for the stockholders. It led to rapid, large-scale loan disbursement to new client segments in order to absorb the financing. These client segments were those that the MFBs did not have time to build relationships with. At the time of writing, MFBs continue to find the management of this new breed of clients difficult.

b. Culture: The model and culture of micro credit lending still influence many transitioning MFBs, from credit-only to full-service microfinance banks. The capacity of the SME segment to meet the demands and needs is still under development, both in the governance and operational levels. MFBs are therefore exposed to risks while serving SMEs, both at the credit origination phase and the monitoring phase. This has contributed to the deteriorating quality of the portfolio.

c. Segmentation: With a wide variety of SME segments targeted, MFBs need more clarity and understanding of the various seasonality and cash-flow patterns associated with each sector. Lack of this clarity has seen some MFBs disburse construction and mortgage loans in one tranche, or venture into sectors like agriculture and education, thus exposing the MFBs to portfolio risks where the cash flows are irregular.

d. Inadequate product suites: Most MFBs are not a one-stop shop for their clients. Due to limited capacity, they are unable to offer a combination of linked products as per their clients’ demands. For instance, an SME client with a corporate account would want the convenience of paying its staff online or view their accounts in real-time. Most MFBs can comfortably offer current and fixed accounts to corporate customers. Salary processing is usually handled by another (commercial) bank because of the MFBs’ limited ATM and agent networks and inability to provide real-time statements. Such SMEs, therefore, end up being multi-banked and multi-borrowed, which hinders their efficiency in loan repayments. Clients tend to be loyal to the institution that serves them with most of their needs hence might not provide real value to MFBs in the long run.

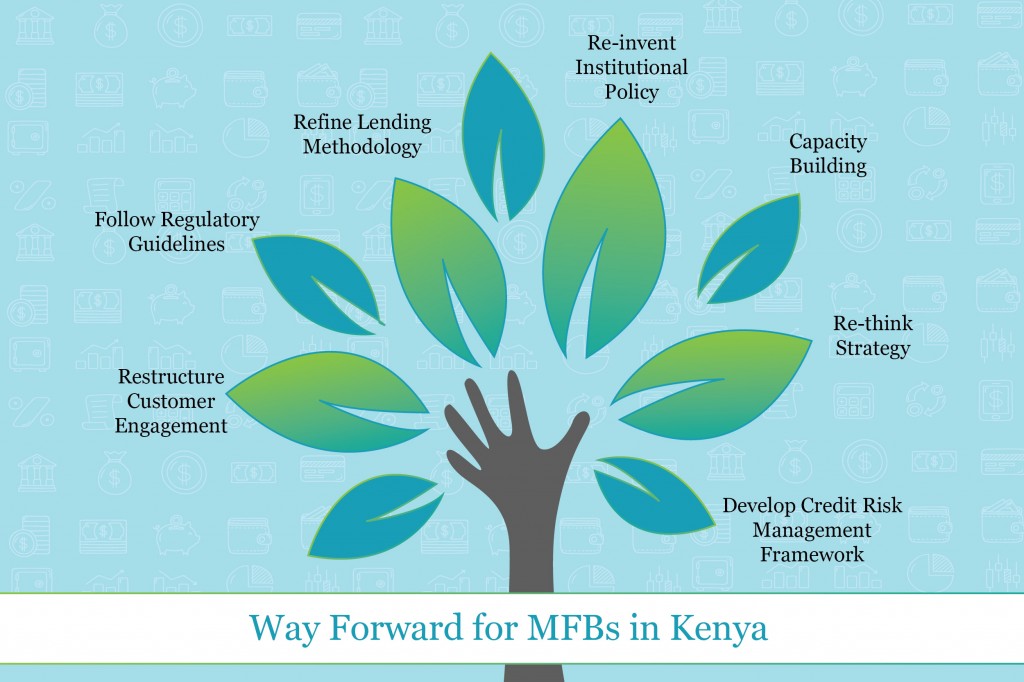

The Way Ahead for the Industry

To capture and even reverse these worrying trends, MFBs in the industry may have to focus on continuous institutional re-invention and capacity-building, from the level of the board to the client-facing staff. MFBs should formulate a detailed strategy that focuses on growing healthy portfolios and outlining risk-mitigation procedures. A customer profiling and segmentation exercise could also be conducted to inform MFBs on risk profiles in each segment targeted, hence improve their lending decisions.

In addition, there is a need to refine lending methodologies and develop a credit-risk management framework for the new segments. A customer relationship management system could also be developed to enhance customer engagement and thereafter boost loan-repayment. Products and services should be reviewed to ensure that they are customer-centric and are able to enhance customer choice, uptake, and usage. For deserving non-performing loans, a restructuring exercise could be conducted, following institutional policy and regulatory guidelines. Please see our publications on issues and solutions in the financial and MSME sector in Rwanda, Uganda, and Malawi for more details.

With the lessons learnt over the past five years, a second transformation in the MFB sector in Kenya may be on the horizon – but that would require hard work and attention to detail.

[1] Analysis based on Annual CBK Supervision Reports and published MFB financials.

[2] KWFT, Faulu Kenya, SMEP, U& I, and Rafiki

[3] Based on a weighted composite index comprising assets, deposits, capital, number of deposit accounts, and loan accounts.

Finclusion to Fintech

Technological developments from the Fintech industry are making waves in developing markets and many have the potential to be customized for developing ones also.

Why Most Agents Networks Will Fail

The Soul of an Agent Network:

The Helix Institute has evaluated and advised all types of agent networks in countries around the world. Big ones, rural ones, new ones, bank ones, and even imaginary inactive ones. Despite the differences in operational strategies, all agent networks should have one element in common – they are crafted to deliver a value proposition to a target market.

That value proposition – the product/service that agents deliver – is the soul of the agent network. It determines the network’s optimal size, growth rate, geographical placement, agent demographics, and the level of training and support that agents receive. It is the foundation upon which all strategic operations are built.

Ironically, despite it being such a defining factor, the value proposition is rarely the issue we are asked to evaluate. Most providers feel like they have got the product right, and remain concerned with secondary issues, such as inactivity in the network, illiquid agents, or a competitor that erodes their market share. However, in our experience, those are generally indicators of larger problems.

Sitting with providers to dissect these problems, we separate the symptoms observed from the drivers that need to be addressed. We unpeel the layers of operations to find elements that have not been correctly woven into the governing strategy. Following these leads frequently guides us to the same place – a value proposition that is simply not very alluring.

An agent network will only ever be as good as the product it delivers. In digital finance, most business models need high volumes to make profits on small margins. Hence, a poor value proposition that is seldom used is going to be a perennial problem. If it does not regularly solve a key concern of the target market, it will constantly struggle to generate income for the business.

Back to the Basics of Product Development

This is not just a problem for small agent networks in the far corners of the world. It is an issue for many of the networks that we evaluate. In our latest paper, Finclusion to Fintech: Fintech Product Development for Low-income Markets, we point out that most of the formal financial products that banks and mobile network operators offer are generally not very useful for low-income people. The resultant uptake and usage speaks volumes:

- Low Registration Rates: The GSMA 2015 State of the Industry Report states that in countries where mobile money is offered, only 10% of mobile connections are linked to mobile money accounts. The 2014 World Bank Findex data shows that only 28% of adults in low-income countries have a formal financial account (bank or mobile money).

- High Inactivity for Those That Register: The 2016 GSMA State of the Industry Report states that only 21% of registered users are active on a 30-day basis. The Making Access Possible (MAP) project studied bank account usage in six countries and found that in one country, 76% of accounts were dormant, while in the other five, 50%–71% of accounts were used as ‘mailboxes’, only to receive an occasional payment.

- For Active, Registered Customers, Usage is Limited and Infrequent: Beyond the statistics shared above on bank accounts, the GSMA 2016 State of the Industry report shares that 97% of volumes and 90.7% of values of mobile money transactions are limited to three usage cases airtime top-ups, P2P transfers, and bill pay. Moreover, the average active user only conducts 2.9 transactions per month (excluding cash-in, cash-out and airtime top-ups).

While lack of access is often touted as the key driver of the low registration rates for formal finance, the inactivity and limited, infrequent usage clearly show that the problem is much greater than just access to these services. In short, most low-income people do not register for formal finance accounts, those that do hardly use them, and those that use them, only do so for limited tasks.

Informal Foundations for Formal Solutions

What is needed is an appropriate set of tools to help people manage their money on a daily basis. Almost nothing we have seen in the market thus far comes close to this. Even when access to formal finance is extended, at best, the mass market incorporates it as yet another tool, but rarely replaces the informal systems and strategies that it uses.

In our paper, Finclusion to Fintech, we compare formal and informal financial solutions and show that the formal ones are not obviously superior as many assume they are. In addition, we review prominent financial inclusion literature and recent data from the Findex and Financial Diaries projects. These help explain why formal financial solutions are not necessarily better, and where product development needs to go to be more valuable for mass-market customers.

The expansion of agent networks across countries has been exciting, but too often the products they deliver are not. New products should avoid trying to improve upon those that people seldom use. They should be built with an understanding that low-income people have unique financial needs and ways of thinking about money management that are still not being met by formal providers. Providers should aim to improve and formalise the often risky informal financial solutions people cling to even when offered formal accounts.

This philosophy should lead the next generation of product development as fintech companies vie to reach the mass-markets of the developing world. Our latest paper is meant to serve as a proverbial Rosetta Stone, translating decades of financial inclusion research into the business opportunities they uncover for fintech innovators. By providing more value for customers, more people would use these products with increased frequency, alleviating many of the most common problems we have seen with agent networks around the world.

View the full report: Finclusion to Fintech: Fintech Product Development for Low-income Markets