I worry that I may be getting old and cynical; but I am quite sure I’m suffering déjà vu.

As we continue to celebrate the important breakthrough that digital credit provides in efforts to lend to the poor, I cannot help myself comparing it with microfinance. The parallels are clear to see:

- Insufficient emphasis on savings,

- Loan amounts too small to make a real difference,

- Reliance on repayment behaviour,

- Drop out patterns,

- Multiple borrowing to get a useful sum,

- One loan used to settle another and

- Rising delinquency.

We seem set to have to learn the same old lessons all over again, the hard way.

I got into microcredit (for that is really what “microfinance” usually is) I could not believe that the industry could place such little emphasis on the importance of savings. Savings that were mobilised by microcredit institutions were typically compulsory, and used as a basis to determine loan size and to act as collateral. Digital credit offerings, when backed by a bank (for example M-Shwari, EazzyLoan or M-Pawa), mercifully do not make savings compulsory and inaccessible to the client, but (when you examine the literature or press coverage) they are still the secondary service that feeds the algorithms that dictate loan amounts. While many customers do indeed use the savings services (and some are thoughtfully designed and structured), many potential borrowers deposit and withdraw in an attempt to game the system to raise the loan amount for which they are eligible.

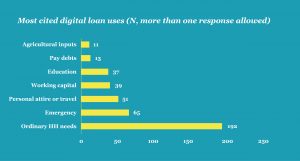

In common with microfinance, the initial digital credit loans are typically too small to be of any real value – except for consumption smoothing, very short-term trading or responding to emergencies. These are all very valid and important reasons to use the service; but the rhetoric and hype around financing enterprises and lifting borrowers out of poverty seems optimistic. This is confirmed by Julie Zollman’s analysis of the FinAccess 2016 data (see graph below) which shows that less than 16% of these loans are used for enterprise.

This leads us to another similarity. For too long microcredit had lived the lie that loans were used for enterprise and simply assumed that microcredit’s impact was beneficial: borrowers were repaying and taking more loans, so there must be positive impact. We seem to be falling into the same trap in our romance with digital credit – perhaps it is time for some rigorous evaluation?

Microcredit institutions have had to simplify and shorten their on-boarding (“training”) processes as competition grew. We can safely expect a similar trend in digital credit. In contrast to the relative simplicity of applying for a loan from M-Shwari, EazzyLoan and other SMS-based systems, app-based lenders’ lengthy and complex application steps discourage many from taking up the product.

The rhetoric around using big data to make loan assessments also seems misleading. Our recent experiment involved working with low income people to apply for loans from all the major providers in Kenya. This allowed us to assess the customer journey, the levels of disclosure of terms and conditions and the resultant loan amounts offered. This exercise demonstrated that (perhaps because of their very limited digital footprints) a poor borrower can put almost any numbers they want into the app-based lending sign-up screens in Kenya and they will receive a standard loan of Ksh.2,000 (US$20) or Ksh.1,000 (US$10) depending on the provider. Thereafter, in common with M-Shwari, EazzyLoan and other SMS-based systems (and indeed microcredit institutions), it is probably your repayment history that will, above all else, determine the size of your next loan.

I strongly suspect that the analysis of “1,000 data points”, social networks and behaviour will be largely incidental to this key indicator of credit worthiness. This may, of course, be different for micro and small business owners using social media to market and digital channels to effect transactions. But for a typical low income consumer who only tops his/her mobile up with a small amount twice a month, and uses a limited number of apps, their digital footprints are probably too light to add much value over and above repayment history. This may evolve with time, as it has done in the United States, where the correlation between Lending Club’s credit rating grade and the borrower’s traditional FICO credit rating score has dropped from 80% in 2007 to 37% in 2015. But this will be highly dependent on low income people beginning to participate more in the digital economy.

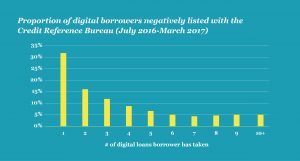

When I first arrived in Uganda, all MFIs were offering loans repayable over four months and living with drop-out rates of 30-60% per annum – hardly the basis for a sustainable business! Analysis showed that, many of the drop-outs occurred after the first loan cycle. These were people who had tried a microfinance loan – often out of curiosity or under peer-pressure – and decided that it was not for them. We see exactly the same challenge with digital credit. Our initial analysis of TransUnion credit reference bureau data showed that over half (57% or 1.4 million) of negatively listed digital borrowers had taken digital loans for the first (and only!) time. And over 30% of the first-time borrowers between July 2016 and March 2017 were negatively listed by the end of March 2017.

However, there is one important difference. With digital credit the lack of personal touch, group guarantee and peer pressure means that the loan losses in this first cycle are extraordinarily high, and is driving many digital lenders to set their interest rates at rates that rival those of informal sector moneylenders. Worse, these interest rates typically do not drop as the borrower builds his/her credit history.

In addition to the drop-outs and default after the first loan cycle, Ugandan MFIs saw a rapid growth in drop-outs in the 5-7th loan cycles. The explanation was simple – many borrowers taking larger fourth, fifth and sixth cycle loans are unable to come up with the larger amounts they needed to meet their weekly repayments. While our analysis of the credit reference bureau data does not show this trend, our recent research in Kenya did highlight some instances of similar issues for regular borrowers eligible for larger loan sizes from digital lenders. The requirement to repay the large lump sum within one month is likely to become increasingly difficult as loan sizes increase. In Uganda, MFIs quickly learnt to extend the loan repayment term to 6 and then 12 months – will digital credit providers follow?

One of the major drivers of repayment crises (for example in Bolivia, India and Morocco) has been MFI staff aggressively pushing loans onto customers. This means that customers who do not want, (or need) to borrow take credit for less important uses, or hand it to their friends and family to use. We see similar trends amongst providers of digital credit who aggressively market their loans (particularly through SMS). As a result, our research showed, some borrowers take digital credit out of curiosity or for frivolous uses such as Friday/Saturday night entertainment or sports betting.

In common with microcredit we are also seeing the rise of two dangerous phenomena in digital credit: 1. Borrowers taking multiple loans to cobble together the lump sum they feel that they need; and 2. Borrowing from one lender to pay off the loans of another. Both, of course, increase credit risk. The better MFIs have tried to deal with these issues by better understanding and segmenting their clients. This allows them to make micro-small-medium enterprise (MSME) loans to those who need, and can repay, larger loans; and to support and manage those who are stressed and borrowing from others to repay. This requires personal interaction, and (for larger loans) a revised approach that involves visiting and assessing the borrower’s business.

It may be that digital credit providers will need to start to learn from the lessons of microcredit organisations and introduce a personal touch into the process, at least for the larger loans. This could be done through involving agents (thus providing them with valuable additional commissions for loan initiation). MicroSave’s work in India has shown that agents are willing to take responsibility for, and get involved in the collection of, loans that they have referred. But they are unwilling to burn social capital by chasing loanees for whom they have not vouched. Without this personal touch digital credit loans will remain last on the list to repay.

Let’s be clear, digital credit is an important, high potential and often valuable financial service for the mass market. We need to work to optimise the delivery and the recovery of these loans, for both consumers and providers. There are plenty of opportunities to tweak and significantly improve the current digital credit offerings. It is clearly time for digital lenders to review the hard lessons learned by microcredit institutions over the past 30 years – if they don’t, we’ll continue to see the alarming numbers of “digital delinquents” and people blacklisted on the credit bureaus.