The Financial Institutions (Amendment) Act 2016, enabled agency banking in Uganda. What can financial institutions launching agency banking learn from existing data on the banking sector, from experience of mobile money, and from client expectations. The Financial Sector Deepening Programme (FSD) Uganda, commissioned MicroSave to find out.

Teams from MicroSave conducted interviews and focus group discussions with bankers, the banked and unbanked, mobile money users, mobile money agents and potential bank agents, mobile network operators and the Uganda Bankers Association. The team studied data available on the Ugandan financial sector including the FinScope Survey 2013, the Intermedia Survey 2015, MicroSave’s Agent Network Accelerator Survey 2015 (from the Helix Institute). Respondents were from rural and urban areas in four research areas.

The case for agency banking: The FinScope 2013 survey suggests that 58% of Uganda’s adult population are potential users of mobile money; of this there are over 14 million unbanked adults. But the startling statistic is that more than 9.3 million adult Ugandans at the time of the survey lived more than one hour away from their nearest bank branch; most of these, some 8.6 million live in rural areas. Well implemented, agency banking can bring a range of banking services to Ugandans who have never had a realistic option of a bank account. Conversely for financial institutions, agency banking offers the potential to onboard, and provide services to large numbers of new customers.

Reaching out to large numbers of customers is feasible. The FinScope (2013) survey shows most transactions occurring in the banking hall are those which can be performed by agents. The leading transactions are over the counter withdrawals (13.8% of total transactions), ATM withdrawals (8.8%) and cash deposits (18%), so called cash in – cash out (CICO) transactions. Information requests (5.9%), receiving money (4.4%) make up the most frequent transactions. This transactional banking can all move to agency banking.

Ensuring a Customer Value Proposition: Focus Group Discussions with bank customers showed, why customers chose existing banking channels – the banking hall was preferred for larger amounts, it was a trusted, safe environment, it had constant liquidity. The ATM was fast, convenient and less costly, mobile banking was easily accessible. Adoption of agency banking should then focus on convenience, cost, a safe environment and liquidity.

Care needs to be taken to price transactions appropriately, banked customers were concerned that some mobile money transactions involving bank to wallet transactions, followed by cashing out were very expensive. Institutions will need to find a pricing point that appeals to customers, and still provides sufficient incentive for agents.

Customers valued bank branches as points to resolve customer care issues, as a place to access information on products and services and a point to access loans; but they felt that lengthy queues, high charges, and system downtime were issues which needed to be resolved. These observations are more problematic for agency banking. Financial institutions will need to invest heavily to provide consistent uptime, expand call centre operations, staff to support reversals and customer onboarding, and train agents to provide quality services. Banks may find it more difficult to sell non transaction based services through agents, however, pulling transactions from banking halls should make it easier for financial institutions to sell more complex products through their own outlets.

Service Offerings: Research with customers and financial institutions suggested that the initial service offerings customers will value the most will be cash in, cash out, facilitating account opening, and credit. Each of these services places specific demands on financial institutions. Managing cash in and cash out requires strategies to monitor and manage cash and float at agents alongside careful agent selection and the creation of appropriate mechanisms to rebalance cash such as intermediaries or so called super agents. According to draft regulations, bank agents cannot open accounts – responsibility for this belongs with the bank, but they can facilitate account opening. However, experience from other countries shows that this works well where there is a National Identification Card where there is a central database of client names and addresses which can be pulled digitally upon request. This is possible in neighbouring Kenya, free of charge for banks, a feature which has helped to grow financial access by making onboarding new customers as easy, simple and cost effective as possible.

The final service requested by potential customers, credit, requires unpacking. Once again agents are not positioned to offer credit services on behalf of banks, but they can, for smaller loan amounts disburse cash, they could be a collection point for information or initial applications and a repayment point for loans (through cash in transactions). The innovation that for many customers would link credit to agents, is mobile phone based instant loans, like M-PESA’s MShwari or MTNs Mocash. Through data analytics financial institutions develop algorithms through which they can provide credit lines to customers, which in turn the customers can access through bank agents.

Customer Preferences for Agents: Potential users surveyed showed a distinct preference for certain types of agents, preferences included petrol stations, SACCOs and grocery shops. However, financial institutions will need to carefully consider that decisions on petrol station involvement are often taken by the franchise owners (rather than the franchisees), and that access to cash in petrol stations is carefully controlled through drop boxes which staff cannot access. SACCO performance in Uganda varies considerably, and screening criteria will need to be developed to source the best SACCOs. Grocery shops are ubiquitous, but tend to struggle more with liquidity management and rebalancing.

Potential users choices for which agents to use were being driven by trust (security), liquidity, opening hours, convenience and space; the factors driving SACCO inclusion were considered to be liquidity and convenience. Potential user preferences for agents included the agent being fluent in the local language plus English, and to have safe, secure, permanent premises. Focus group discussions indicated a preference for SMS receipts amongst non-banked and a preference for a physical receipt amongst the banked.

Factors Promoting Agency Banking: The factors promoting agency banking differ according to the group – banked users appreciate the convenience likely to be experienced by agency banking, whilst non-banked users are looking for less costly services. Banked users noted reductions in risk from carrying cash long distances, and reducing the cost of transport to the bank.

Will Agency Banking Increase Movement Between Institutions? The sample size is too small to conclusively answer the question of whether the introduction of agency banking will increase movement between financial institutions. Research suggested the factors which might keep people with an institution included the challenges of opening another account, the fear of untested services, and the existing history (and trust) that had been built with an institution. However, agency banking, combined with easier onboarding due to the National Identity Card offers the potential for customers to easily switch between institutions or to hold multiple accounts. The financial education which may accompany the launch of agency banking, combined with peer to peer learning, may further decrease friction and encourage competition between financial institutions.

The Concerns of Potential Customers: Potential customers were most concerned about fraud, and illiquidity, followed by network instability and the lack of electricity. These concerns have been noted in other survey’s such as the Intermedia Survey (2015) and MicroSave’s Agent Network Accelerator Survey (2016) from the Helix Institute. In fact Uganda has the highest incidence of mobile money fraud reported by agents out of ten countries in which MicroSave has conducted extensive surveys. This points to the importance for Uganda’s financial institutions in developing risk management frameworks, and risk mitigation strategies. The very fact that banks are often perceived to be safer than mobile network operators may offer banks an advantage in agency banking over their mobile money counterparts.

Likely Characteristics of Successful Bank Agents: The Agent Network Accelerator Survey indicates whilst most agents have less than a year’s experience in mobile money, the most successful mobile money agents are more established in their businesses. The research suggested that mobile money agents were less likely to have audited books of account and to pay tax on their business than more mature businesses; factors which will need to be considered during agent selection.

Understanding the Expectations of Agents: The biggest motivators for potential agents were commission income, the potential to cross sell other services to agency banking customers, and to create employment. At the same time, potential agents have expectations of banks, the most frequent expectation was for training, the second was for commission income, the third for sensitisation of end users, and to provide the necessary tools of the trade. Other slightly less requested asks included supervision, working capital loans, and liquidity management support. Financial institutions introducing agency banking will need to develop a package to meet these expectations. Most mobile money agents felt that banks would have tighter compliance requirements than mobile money operators, but felt that they would be able to meet them.

Factors for Success from an Agent Perspective: Whether mobile money agents, or established businesses, the most common success factor given by respondents was a high public awareness campaign, the second a good network signal. The established mobile money agents showed their perceptions of fraud, by also listing currency detectors, and video cameras.

Motivations for Banks: The most common motivations for banks considering agency banking is client acquisition and increasing activity on customer accounts. Additional motivations included decreasing cost to income ratios through better utilisation of bank assets, and to decrease congestion in banking halls, and finally to decrease the cost of deposits. All banks believe that numbers of accounts will increase, some think this will be a rapid change, others more gradual, the majority of the respondent banks feel that dormancy will decrease, and that new product development focusing on the channel will be important. The anticipation is that the launch offerings will be similar, including cash in cash out, balance enquiries, bill payment, facilitating account opening, loan repayments and loan disbursements. Thereafter innovations around credit are anticipated.

Enabling Customer Recourse: Agency banking by nature utilises networks of third parties whether agents, merchants, system vendors, super-agents, aggregators, and other financial institutions. This network of relationships and reliance upon third parties creates many points at which transactions can fail; in addition to the mistakes made by customers, and deliberate fraud. These circumstances call for advanced customer service recourse. Sector respondents identified a range of options for customer recourse, including agency banking supervisors in branches, call centres – with numbers displayed in merchants. However, respondents identified empowering agents, enabling them to be a first point of contact as an important resource, to do this, careful selection and training of agents is required, alongside supervision and refresher training. Toll free call centres are also important to facilitate recourse for all customers

Unlike countries like India, where agents electronically top-up airtime for customers, airtime scratch cards seem to be the most preferred mode of self-top up among Malawi’s growing base of mobile subscribers.

Unlike countries like India, where agents electronically top-up airtime for customers, airtime scratch cards seem to be the most preferred mode of self-top up among Malawi’s growing base of mobile subscribers.

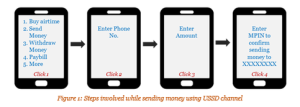

Overall, the research finds that most customers are aware of the convenience associated with mobile money services. This primarily includes storing money to avoid cash holding risk, transferring money on their own, the convenience of airtime top-up and paying utility bills anytime and anywhere, among others. Simplified USSD interface and convenience to use mobile money services are the major factors leading to higher uptake and regular usage of mobile money, reduced dependence on agents for transactions and increased self-usage of mobile money accounts by customers.

Overall, the research finds that most customers are aware of the convenience associated with mobile money services. This primarily includes storing money to avoid cash holding risk, transferring money on their own, the convenience of airtime top-up and paying utility bills anytime and anywhere, among others. Simplified USSD interface and convenience to use mobile money services are the major factors leading to higher uptake and regular usage of mobile money, reduced dependence on agents for transactions and increased self-usage of mobile money accounts by customers.