The Nachiket Mor Committee on “Comprehensive Financial Services for Small Businesses and Low Income Households” made some concrete recommendations to enhance the spread and use of formal financial institutions. These recommendations include methods to transform the way government distributes social welfare funds. If the recommendations are accepted as they are, Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) will go through a sea change. In this blog we assess the recommendations that impact “Direct Benefit Transfer”.

The most revolutionary, and therefore the most talked about, recommendation is the provision of a “Universal Electronic Bank Account” (UEBA), for each adult Indian using Aadhaar as e-KYC. This fulfils the most basic and critical condition of receiving direct benefit transfers: having a bank account. Significantly, the report recommends that these accounts are opened as soon as the Aadhaar identification number is issued, so that the time taken to open an account is reduced to almost nil.

The alternative method for opening an account, through the normal route of filling an application form, submission and verification of KYC documents etc., takes a long time, usually an average of 15 days … and in some cases the account is never opened at all.

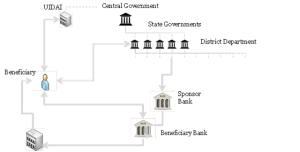

Beneficiaries of different DBT schemes either do not have bank accounts; or if they have one, linking (or “seeding”) the Aadhaar number to these accounts is extremely challenging, because of discrepancies in the databases involved, and the low number of bank branches (because seeding can be done only in a bank branch). If the method of account opening proposed by the Mor Committee actually materialises, it will solve one of the bigger impediments that has contributed to uncertain and painfully slow progress of DBT – that of beneficiaries not having Aadhaar-seeded bank account. Apart from a handful of States where non-Aadhaar transfers are working well (for example Madhya Pradesh), for the majority of DBT schemes, Aadhaar seems to be the only reliable and feasible option. The recommendation for the UEBA takes care of both necessary conditions: a bank account that is also seeded to the beneficiary’s Aadhaar number.

The RBI has already allowed use of Aadhaar as e-KYC, but Indian banks have, to date at least and for understandable reasons, demonstrated a high level of inertia, and are taking too long to accept and respond to the new realities. It will take a few progressive banks to take initiative and provide the proof of concept, after which all banks will rush to follow.

While UEBA will address the necessary conditions – a bank account and seeding with Aadhaar – for DBT, where will beneficiaries withdraw the money? The Mor Committee report discusses this issue as well and makes more recommendations to increase the number of access points in remote and rural locations. This can be done if the government increases commission paid to the banks for G2P payments to 3.14% of the amount transferred – thus making rural agents or customer service points (CSP) viable. This should take care of the viability issues for banks, aggregators and agents even in locations where the number and value of transactions is relatively low.

Another recommendation of the committee is to make the BCs interoperable. Under the current approach banks follow the “service area” approach to set-up business correspondent (BC) touch points. This means that each service area, is serviced by the area’s designated bank. Without interoperability, these touch points do not add lot of value to many clients who have accounts with a variety of banks – many or all of which do not have a BC touch point in their vicinity. If BCs are made interoperable, rural bank account holders will much better served and the business case for BCs and their CSPs will be greatly enhanced.

These recommendations potentially can transform the BC landscape by reducing the number of dormant CSPs, and also multiplying the number of access points available to beneficiaries irrespective of their parent bank and aggregator. The current state of CSP presence in India is not very encouraging as has been highlighted in a recent MicroSave India Focus Note “The Curious Case Of Missing Agents In Rural India”. The study shows that only 4% villages could really be considered to have effective or usable CSP coverage. In other places, CSPs were either dormant or were never appointed, and others simply do not exist at all. Until steps are taken to ensure viability of business proposition for banks, aggregators and agents, we can safely assume that neither Aadhaar-enabled benefit transfers nor financial inclusion will take off.

The Mor Committee’s report also makes a few other recommendations that have potential to change the BC landscape and provide much more room for banks to make business decisions. The recommendation to discontinue the requirement for bank branches to be within 15 km (urban) / 30km (rural) of their CSPs will help to make the case for banks to treat this as mainstream business and thus take a business decision on where to place their CSPs. It will be a welcome break from current target based approach. Another of committee’s recommendations, that banks can decide on charges for clients transacting at CSPs, also strengthens the business case for banks, BCs and their agents. There are locations in remote areas of hilly terrains where it may just not be feasible for banks to offer BC services at the same fee/commission as is in cities and towns in plains. If banks are free to decide charges, they will be more willing to open CSPs even in otherwise ‘unviable’ locations. And because all banks will be free to do this, competition should check exorbitant pricing.

Thus the Mor Committee’s report has addressed all the basic factors that are needed to make DBT successful and help achieve universal financial inclusion. The report challenges regulators to provide favourable conditions for fair and open competition, so that India has a larger number of viable players offering financial services. The regulator should recognise and respond to these new realities/possibilities. This is indeed new age, and new age banking provides us the opportunity to finally realise the dream of financial inclusion using DBT as an “anchor product” on top of which banks can offer a larger range of services.

Business as usual is not working and is unlikely to do so in the foreseeable future!!!